This paper was written for the Global Investigative Journalism Conference held in Lillehammer, Norway, in October 2015 as part of the academic track and presented there.

The simultaneous development of a Teaching Lab and a non-profit platform for investigative journalism in The Netherlands

An integrated practical and methodological approach

By Marcel Metze with De Onderzoeksredactie

Summary

Four years ago an experienced investigative journalist (the author), and a small, respected weekly magazine in The Netherlands, started a program for training young journalists called The Investigative Teaching Lab, which was subsequently embedded in a new non-profit organisation for investigative journalism called De Onderzoeksredactie (The Investigative Desk). This paper focuses on the core principles of this project. The Lab and the editorial platform are based on the conviction that the investigative journalist as a ‘soloist’ will eventually become a dinosaur. The size and scope of societal problems, the use of new investigative methods and techniques, and the need for multiple narrative styles demand the introduction of a multidisciplinary team model. The students in The Investigative Teaching Lab and the journalists of the nonprofit platform work in such teams. The (learn to) employ classic journalistic methods and modern data-journalistic techniques but also (learn to) use insights from ‘interpretative qualitative research’ methodology and from constructivist social sciences. Thus, The Investigative Desk wants to professionalise and strengthen the methodological base of investigative journalism and develop a new approach which offers a better framework for triangulation and improves both the accountability of research and the (narrative) quality of investigative productions. The stories of Lab and Desk have attracted widespread attention in The Netherlands, other media are lining up to co-operate, and the project has been growing rapidly, both in production and in funding.

1. The start

In 2004, two institutes for higher education in the city of Utrecht, The Netherlands, started an investigative journalism master. One of them specialised in vocational training programs and was the home of the oldest school of journalism in the country. The other was a scientific university with a wide range of bachelor and master programs in the main academic fields. Together, they intended to professionalise the education of investigative journalists in The Netherlands by joining forces in a master program that would combine practical journalistic skills with methods and insights from science. However, a year after the start they did not acquire an official accreditation. The assessment panel criticised the content, structure and coherence of the program, and was not impressed by the quality and qualifications of the staff that had been assigned to it. The program lost its government funding and was stopped.

The author of this paper, an experienced well-known investigative journalist in The Netherlands, was a member of the aforementioned assessment panel. Some years later he contacted a number of other Dutch universities to see if they would be interested in a second try in setting up an investigative journalism master program. He met no enthusiasm.

Then, in 2010, the editor-in-chief of De Groene Amsterdammer, a small intellectual weekly magazine, suggested that he might develop his own ‘master class’ and offered support. 1 An announcement in the magazine and on public radio led to over 130 applications. Five participants were selected, of whom four actually took part. All had academic degrees (MA), two had working experience as journalists. They didn’t have to pay a fee but were required to invest a minimum of three days per week of their time. After a 2-day introduction and two weeks of initial desk-research in January 2011, the group selected two issues, split up in subgroups and set out on a 4-month investigation. Every week they reported their progress. This author coached them, shared his experience, provided tips & tricks and discussed professional literature and inspiring examples of journalistic research with them.

After two months, one subgroup dropped its subject for lack of progress and joined the other team. Based on FOIA requests, the group revealed that local governments in The Netherlands had been supporting their top-league football clubs with more than a billion euros over a period of 15 years, using loopholes and creative financial constructions to avoid EU-regulations forbidding such support (Den Boer, 2011; Engbers, 2011; Logger, 2011; Pinster, 2011). Their report and interactive map were published in De Groene Amsterdammer magazine and website, and drew widespread media attention. The publication prompted EU-officials to look into a number of the described cases and forced local governments to adopt a more critical attitude towards financial requests from the clubs.

Despite this journalistic success, the first trial also made clear that the program needed expansion and methodological strengthening so we decided to extend the duration to 5 months and to bring in someone with expertise in the development of teaching programs for young professionals.

Moreover, we quickly realised that we were teaching the students skills and expertise for a threatened profession. Like in other western countries, journalists in the mainstream Dutch media had seen an gradual increase of production pressure and decrease of available time and budgets for in-depth, large-scale investigations since the eighties. For freelance journalists it had even become almost impossible to finance such investigations. This was particularly frustrating because the complexity, interconnectedness and international scope of many political, economic, social and environmental problems requiring journalistic attention was increasing.

Still, at the same time there were signs of a new and maybe even better future for investigative journalism. One was the rapid development of new computer-techniques for data-analysis and data-visualisation. Another was the search for new business models, reflected in the growing number of non-profit organisations for investigative journalism, first in the USA but quickly also on other continents. A third sign was the increasing international co-operation of investigative journalists in networks like Global Investigative Journalism Network and International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a trend that unquestionably got a huge impulse from the release of the WikiLeaks datasets since 2007.

This mix of destruction and innovation indicated the advent of a disruptive phase in investigative journalism. So it seemed appropriate to offer the alumni of our ‘master class’ program the opportunity to carry on developing their skills and experience in the front ranks of that disruptive movement, rather than moving on to the mainstream media and being captured in their high-pressure news-production systems. After two years the program had bred a dozen talented young investigative journalists, and we invited them to become co-builders of a new non-profit organisation for investigative journalism that would focus on teamwork, data-journalistic techniques, big research projects, new narrative forms, and, as soon as it had established itself,on international co-operation. The master class program would be incorporated in the new non-profit and renamed Investigative Teaching Lab.

In the preparatory phase, the project name of the new non-profit was Tarbell, after Ida Tarbell, the famous American muckraker who exposed the secret power games of oil-magnate John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil in the early 20th century. However, this name did not meet with a wide response in the younger generation of Dutch journalists. So shortly before the actual launch in March, 2014, it was changed into the functional, though admittedly less colourful, De Onderzoeksredactie (The Investigative Desk).

2. Developing the Investigative Teaching Lab

Since January 2011 we organised seven editions of the Investigative Teaching Lab. After the first edition, which was essential a trial-and-error run, we brought in an outside expert with experience in training young, highly-educated professionals and started building a real program and curriculum.

This building process brought along a number of practical changes. We raised the admission age to 25 years to stimulate applications of university postgraduates who already had some work-experience. Since learning to co-operate in big projects was a teaching goal, we decided to no longer allow multiple research topics but to ask the groups to select and investigate a single topic. To give the participants a better idea of what to expect of the Lab we invited alumni to share their experiences (which they did enthusiastically). Furthermore we expanded the first phase of the program (the selection of the research topic and the development of a research plan), and the final phase (of collective writing), bringing the total duration to 5, and later 6 months.

The first trial had shown that, no matter how talented or experienced the participants were, they all needed to work on their skills. So we introduced practical workshops, tailored to the investigation at hand (e.g. networking analysis, analysing annual reports, writing FOIA requests, using LinkedIn as a research tool, Excel and scraping).

To give the program more theoretical and methodological strength, we selected some texts that would help sensitise the participants to more complex and multi-level, multi-perspective investigative approaches. Three of those texts are worth highlighting, all written by authors who regularly contribute to The New Yorker:

- Explaining Hitler by Ron Rosenbaum (1998), a book in which the author describes his odyssey to find the true nature and causes of Adolf Hitler’s evil, not by looking for new facts but by thoroughly investigating the existing evidence and perspectives offered by the most important Hitler biographers. Rosenbaum teaches us that in complex matters there often is not a single truth, but one may be able to end up at a well-grounded, most convincing explanation. Many teaching lab participants found reading and discussing this book a fundamental and mind-expanding experience.

- Open Secrets by Malcolm Gladwell (2007), an essay in which he analyses the Enron case by using the dichotomy puzzle vs. mystery. Gladwell shows us that many journalists treat the cases they investigate as puzzles that can be solved by collecting enough pieces of information. In fact they mostly have to deal with incomplete sets of facts which require intelligence and analytic skills to interpret sensibly and convincingly.

- Truth Wears Off by Jonathan Lehrer (2010), a report in which he analyses the weakening of scientific results in repeated replications. Lehrer shows that this 4 weakening is mainly caused by bias, both in the selection of data and in the interpretation of results. Most journalists, even the best, are unaware of the dangers of bias, as became apparent in 2014 when a Rolling Stone story on a campus rape proved seriously flawed, partly because of ‘confirmation bias’. 2

In addition, we introduced texts that would stimulate the participants to reflect about methodology, interpretation and perspective, by a variety of authors such as the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg (1992), notably his essay Clues, Roots of an Evidential Paradigm; the autobiographic Geschichte eines Deutschen (Story of a German) by the German journalist and biographer Sabastian Haffner (written 1939, first published in 2000); and the American sociologist Richard Sennett, the author of, among others, the Corrosion of Character (1998). And of course we started using and discussing handbooks, such as the excellent and still very useful The Art and Craft of Feature Writing by William Blundell (1988), and books about the media and the journalistic profession such as Nick Davies’ Flat Earth News (2009) and Jan Blokker’s critical book about journalism in The Netherlands, entitled Nederlandse journalisten houden niet van journalistiek (2010) – Dutch journalists don’t like journalism. 3

2.1. First evaluation (2012)

An evaluation by participants of the first three editions (9 of 13 participants filled out evaluation forms) showed them positive to very positive about the coaching style and the literature package, but less so about the coherence of the various elements of the curriculum. They also had problems with organising and planning their work.

In response we began developing a toolkit for teamwork, which eventually came to include a range of templates (e.g. for research memo’s, logs, and interview transcriptions) and software tools such as a desktop search engine, database programs, Dropbox, Google Docs & Drive, Asana, etcetera. To make work-planning easier we gave the curriculum a clear structure of four phases, taking a total of up to 22 weeks:

- introduction, selection of topic, initial desk research, writing of research plan (3 weeks);

- main research phase (10 weeks), concluded by a full-day lacuna session to trace deficiencies and gaps in the investigation;

- additional research to address lacunae (3 to 4 weeks);

- writing phase (4 to 5 weeks), starting with a full-day construction session to develop the storyline.

Please note that this approach differs fundamentally from the ‘story-based enquiry’ approach. We believe that investigative journalism begins with asking relevant questions and doing in-depth research. First one has to collect a substantial amount of observations and interpretations. Then the time comes for developing storylines and analyses and explanations.

2.2. Second evaluation (2014)

Internal tensions in the fifth and sixth groups, both in 2013, made it clear that journalistic teams like those in the Teaching Lab situation, which have not formed themselves but are artificially constructed, do not automatically flourish and that team dynamics may cause paralysing problems. To get a better understanding of this aspect, we asked an external expert to do thorough observation and evaluation of the team development process and indeed of the entire teaching lab process.

The expert and an assistant attended the weekly meetings of the 7th edition, which took place from May through November 2014, and concluded that the setup and program faced some structural weaknesses:

- The collective and individual targets and the criteria to assess, at various stages of the project, which participants were developing well and were showing the talents and qualities to become top-level investigative journalists, were not clear enough;

- As a result of these unclear assessment criteria, the participants were unsure what was expected of them in terms of effort, time investment, production and results.

- The participants were learning how to set up and conduct an in-depth journalistic investigation but also had to produce a 10,000 word article plus visualisations about their findings. These two goals weren’t necessarily consistent with each other and caused a structural tension in the teaching / learning process.

The expert concluded that the Lab needed further professionalization and recommended that it:

- explicit its definition of what it considered good investigative journalism and describe the corresponding methodology;

- set clear targets for the individual participants and collective targets for the groups;

- expand its set of teaching methods, and especially introduce more and better targeted practical exercises;

- develop ways to assess individual and collective performance at various stages of the project;

- address the tension between the learning process and the pressure to produce. A group might do good research but lack the ability to produce a good story. In such cases the project should be ended without a publication or the story might be written by an experienced author (as had in fact had happened twice; in both cases the coach had written the final article based on draft texts from the group).

The Lab should also:

- expand the pool of external teachers and trainers;

- appoint a program manager and an assistant to the coach;

- form an advisory council with members from the journalistic and academic community.

2.3. Developing a new curriculum

These recommendations stimulated a thorough revision of the curriculum, the outlines of which we sketched in the spring of 2015. It was clear that we were already working toward an investigative methodology with a dual core of qualitative and quantitative methods and techniques.

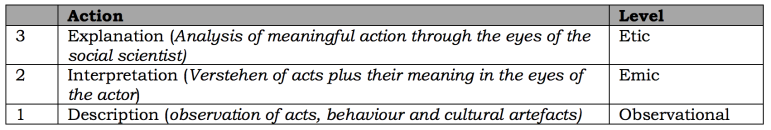

On the qualitative side we now chose the model for naturalistic research that was developed by the social scientists Dr. Joost Beuving, who teaches anthropology at Radboud University of Nijmegen, and Dr. Geert de Vries, a teacher of sociology at the VU University of Amsterdam. Their trichotomy of observing, understanding and explaining (Beuving & De Vries, 2015) originates in the hermeneutic tradition within the social sciences and in the sociological school of symbolic interactionism. Beuving & De Vries developed it for what they call naturalistic inquiry but as table 1 shows it is in many ways very useful for journalistic inquiry as well. At the ‘observational’ level both the social scientist and the investigative journalist concern themselves with the naked description of behaviour and actions. At the ‘emic’ level both try to understand 6 how the people involved interpret their own behaviour, while at the ‘etic’ level they try to explain this behaviour from an outside, analytical point of view.

Table 1. Three levels of meaning in naturalistic inquiry

(Beuving & De Vries, 2015)

We found Beuving’s & De Vries’ handbook Doing Qualitative Research (2015) especially attractive for investigative journalists because even as they focus on qualitative methods they are not averse to quantitative research. On the contrary, they feel that both approaches can and should be complementary. Likewise, in our Teaching Lab we stimulate the combination of quantitative data-analytical research techniques and ‘old school’ qualitative journalistic methods.

To find out whether similar dual approaches had already been developed elsewhere, we made study tours to the 2013 IRE Conference in San Antonio, Texas, the 2013 Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Rio de Janeiro and the 2014 Data Harvest Conference in Brussels. In 2013 we also visited ProPublica, the exemplary nonprofit platform for investigative journalism, based in New York City, and prof. Sheila Coronel of the Toni Stabile program at Columbia University, who later also kindly sent us the syllabus of her investigative seminar 2014. These tours and visits provided us with a good view of the proven data-journalistic technology as it had developed in the USA in the previous decade, and inspired us with ideas about how to combine these techniques with qualitative journalistic research methods, both in an editorial (ProPublica) and in an educational setting (Columbia).

The revision of the curriculum will result in an expansion to a 6-month semester, structured in 6 phases. We will increase the number of workshops and visiting lecturers, and introduce individual assignments to facilitate individual assessments. We will realise a closer integration of the workshop, lectures and literature with the various phases of the investigative project. In order to create a closer connection between the Teaching Lab and De Onderzoeksredactie we will introduce workshops and sessions that will be led or moderated by Lab-alumni who now work on our editing staff. 4

In the long run, we expect a further expansion of the program to 2 semesters. We also foresee a further methodological development, based on a more active use of discourse analysis and social constructivism theory, both of which journalists may find useful for analysing the way the people they investigate rationalise their behaviour. In fact, when investigative journalists work together in teams they already use social constructivist mechanisms to develop grounded collective perspectives.

The next section will offer some remarks about the differences between our program, as it has developed until now, and four other programs, in the USA, UK and Belgium.

2.4. An international comparison

During the development of the new curriculum, the Investigative Teaching Lab took a look at the programs offered by

- Columbia School of Journalism, Toni Stabile Centre (Investigative Seminar);

- City University London (MA Investigative Journalism Programme);

- Thomas More University College Mechelen, Belgium (postgraduate course International Investigative Journalism);

- Berkeley School of Journalism (Investigative Reporting Program)

We only used public information from the university websites and in Columbia’s case also the 2014 syllabus that prof. Coronel kindly made available for us to read. From this information we get the impression that Thomas More University in Mechelen, Belgium, focuses on teaching (post)graduates a set of practical journalistic skills that should help them to become an all-round freelance ‘entrepreneurial’ journalist. The Thomas More students follow workshops and work in pairs on an investigative project. Once finished they have to find a media outlet that wants to publish their story. The MA program of City University London has a traditional structure. It offers workshops for developing skills and knowledge-enhancing lectures on specific topics. The program co-operates with the philanthropically sponsored non-profit organisation The Bureau Investigates.

Students at the Columbia School of Journalism can choose the Toni Stabile program if they want to acquire an MSc degree with a specialisation in investigative journalism. The program has three courses. Two teach both traditional and modern datajournalistic skills and techniques, the third examines “the tectonic shifts that are taking place in the media” and challenges students “to think about how they can produce, pitch and fund investigative stories in such a dynamic environment”. This course also wants to familiarise students “with the investigative tradition and the traditional investigative narrative forms”.5 Columbia students work on an individual investigative project and a group project. Berkeley’s program, finally, is based on the motto ‘learning by doing’. Students work on an in-depth project, either alone or in pairs or teams, and follow a variety of practice-oriented courses, often given by visiting lecturers. On the website, veteran journalist Lowell Bergman, who has been running the program for more than two decades, writes : ‘The only way to learn investigative reporting is to do it. But doing it is always more productive if you have a guide.’6

As indicated, the Investigative Teaching Lab we developed in The Netherlands does not function in a university context. Nevertheless, there are obvious similarities with the programs at Berkeley and Columbia. We too stress the importance of ‘learning by doing’, under excellent guidance. Just as Columbia, we explicitly focus on combining classic methods with new, data-journalistic methods and techniques. Even more than in Columbia’s and Berkeley’s program, the investigative project is the centrepiece of our curriculum. It is this central position of the investigation as a learning experience that has prompted us to call our program a ‘laboratory’. By contrast, we get the impression that City University London and Thomas More University at Mechelen regard themselves primarily as training institutes and put more emphasis on teaching than on learning.

The Investigative Teaching Lab seems to differ from the other four programs in two ways:

- We have chosen a team-based approach, based on the conviction described earlier in this paper: the size and scope of societal problems, the use of new investigative methods and techniques, and the need for multiple narrative styles and multi-media publications simply demand that journalists learn how to work in multidisciplinary team settings.

- We explicitly aim at strengthening the methodology and toolkit of investigative journalism by importing insights, theories and methodologies from science. The results of this effort are already clearly visible in the program and also in a number of our productions (see section 4 on Results).

3. Developing The Investigative Desk (the non-profit platform)

In the first paragraph of this paper we described why we decided to embed the Investigative Teaching Lab in a new non-profit organisation and web-platform for investigative journalism. Such a platform did not yet exist in The Netherlands but the circumstances seemed fit and when we started developing the plan we soon got indications that it might be possible to acquire philanthropic funding. We acquired such funding in November 2013.

De Onderzoeksredactie (Dutch for The Investigative Desk) was launched on 26 March, 2014, with an editorial staff of a dozen freelance journalists and a small budget of € 130,000. Its mission was inspired by ProPublica’s ‘journalism in the public interest’, though in some respects more modest, and stated that we would:

Investigate the institutions of power, provide insight in the way they operate, and expose their abuses and violations of public trust. Thus, we want to contribute to the public debate, to a better democracy and to a higher level of societal integrity.

3.1. A team-based, multi-method, multi-perspective approach

Like the Teaching Lab, the editorial staff of De Onderzoeksredactie focuses on teamwork. We don’t believe in the investigative journalist as a lone wolf but prefer working in groups of two to six with multiple skills and disciplines. Like in the Investigative Teaching Lab, in the research teams we use modern data-journalistic techniques and classic journalistic methods but also insights from social sciences and ‘interpretative qualitative research’ methodology.

Our multi-method, multi-perspective approach is best conceived as a framework for a variety of scientific and/or journalistic methods. By investigating one question with different methods a team can triangulate its findings. This improves the accountability of research and (narrative) quality of productions. The approach tends to put more focus on the structural factors which ‘produce’ of stimulate individual misconduct and frequently leads to a revision or even total up-ending of the central research questions. An example is our investigation into the systematic budget overruns of public ICT projects in The Netherlands. Updates and new software systems for agencies like the inland revenue service or for paying-out government subsidies cost the Dutch taxpayer billions of euros per year more than budgeted. The ICT-companies that build these systems blame the overruns to a lack of expertise in the government. We started from that hypothesis too, but found that in fact something else is going on. Governmental ICT-departments hire substantial numbers of experts from the companies to design and develop the new systems, and even to assist in organising the government tenders. These detached experts have no reason to apply strict budget controls and get plenty of space to draw out projects almost indefinitely by proposing follow-up projects, even better systems, etcetera.

3.2. Organising the investigative process

Our investigative projects follow a series of well-defined steps to go from idea to story (these steps are similar to the phases of the Teaching Lab program):

- Pitch: the person with the initial idea will ask the editor-in-chief permission to pitch it to his/her colleagues during an editorial meeting. The initiator will have to convince his/her colleagues and the editor-in-chief that the proposed project is original, important and relevant. He or she will also have to make clear how the idea fits in our thematic specialisations, and indicate whether it will be suited for follow-up research or a series of articles.

- Research plan and team formation: if the idea still stands after the pitch, the initiator will form a potential team, do preparatory research and write a research plan, which is again discussed during am editorial meeting. We encourage multimethod research, including data-analysis, network-analysis and surveys. The research plan has to include first ideas about the narrative forms in which the story will be presented and about possible data-visualisations such as graphs, search-able databases and interactive maps.

- Determining a budget and a funding plan, and finding media partners: in its research plan, the team will estimate how much time and money it will need, and indicate a) which media partners might be interested to participate, b) which subsidies they intend to apply for, and c) what investment they expect from De Onderzoeksredactie itself. We call this ‘hybrid funding’. We usually manage to find around 50 percent co-funding.

- Start: once the editor-in-chief has approved the research plan, the project is ‘on’.

- Lacuna session: when the research phase is about halfway, the team and the editor-in-chief discuss the initial findings and further research strategies during a ‘lacuna session’. This session may result in an adjustment of the research question.

- Construction session: before the team starts writing and producing, it sits with the editor-in-chief to develop and discuss the storyline during a ‘construction session’.

- Writing: may take up to six or seven versions. We don’t set a deadline until there’s enough certainty that the story will be good.

3.3. Developing specialisations and collective quality standards

The procedure described above ensures that weak ideas will not be pursued longer than necessary. It gives us an early impression of the feasibility and costs of a research project, and it provides for continuous coaching and monitoring during the entire project. The procedure makes it harder for individual editors to start their own hobby projects and stimulates the development of specialised teams and of a collective editorial policy. Even more important: it stimulates a continuous debate with the entire staff about what De Onderzoeksredactie shall regard as relevant themes, good research methods and interesting perspectives.

To feed this debate we also started bi-weekly evaluation sessions, in which the editors discuss their own publications and stories in other media they find interesting. These ‘benchmarking’ sessions quickly provoked a discussion about our quality standards and our views about what makes investigative journalism excellent. We plan to continue these discussions for some time and try to develop a coherent vision that we shall put on paper in 2016.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the investigative lab (2011-2014)

As indicated earlier in this paper, we organised 7 editions of the Teaching Lab, the first one in 2011 and the last one in 2014. Due to financial uncertainties it has not been possible to run the new curriculum in 2015 but is expected to start in 2016.

A total number of 30 people participated.7 Of these:

- 11 continued as investigative journalists (of whom 10 at The Investigative Desk);

- 9 became general freelance journalists;

- 1 came from and returned to commercial radio;

- 2 were accepted as PhD-candidates;

- 7 pursued another career (university teacher, policy researcher, etcetera).

The seven labs investigated:

- creative financial constructions to avoid EU-regulations against government support to commercial football clubs;

- the consultancy firm McKinsey & Co. and the way it collects, repackages and sells sensitive corporate information, partly by using its extensive alumni network; – invasions of employee privacy at and outside the workplace;

- conflicts of interest in the Dutch national energy system (the government officially aims at CO2 reduction but has a large stake in the sale of natural gas);

- the consequences of the privatisation of the public housing sector in The Netherland, which resulted in dubious investments, greedy executives and huge financial losses – at the expense of the lower classes and the taxpayers;

- the consequences of the privatisation of the health care system in The Netherlands, which should have improved both cost control and the quality of treatments. Instead it resulted in higher costs and put the management of the system in the hands of an oligopoly of four major insurance companies who are primarily interested in their own balance sheets and have no clue how to measure the quality of health care let alone improve it.

- conflicts of interest facing university professors with extracurricular activities and positions. The team scraped the university websites and produced a searchable register of such activities and positions for all 5,800 university professors in The Netherlands. A deeper investigation of a representative sample revealed that, contrary to transparency rules, many of them do not report their extracurricular activities. The project also showed that many potential conflicts of interest are looming below the university work-floor, and that additional systematic research may lead to further revelations.

Most of the Lab’s publications got widespread attention in the Dutch media, some led to questions in parliament, and in a couple of cases they had a discernible impact on policy- and decision-making. One was nominated for an award for investigative journalism. One of the Teaching Lab alumni-teams later won this award for a follow-up story.

4.2. Results of the non-profit platform

De Onderzoeksredactie (year 1) In the first twelve months of its existence De Onderzoekredactie (The Investigative Desk) published a total of twelve major investigative stories: two Teaching Lab dossiers and ten long-read stories produced by editorial research teams.

Four of those ten stories were part of a co-operation with regional newspapers and regional public television stations, in a project which investigates how local and provincial governments in The Netherlands are spending the about 40 billion euros they have earned from privatising their energy companies. Based on research by De Onderzoeksredactie, the regional media partners produced 40 stories and televisionitems. De Onderzoeksredactie collected these on its website and made them accessible by way of an interactive map.

In the other big stories journalists of De Onderzoeksredactie investigated, among others:

- the fate of young African football talents who are lured to Europe with false promises,

- the involvement of Dutch financial offshore companies in a fraudulent scheme to divert profits from the transfer of Rumanian football players,

- billion-euro losses of the Dutch state company that owns and exploits the national distribution network for natural gas, and

- the causes of systematic cost overruns in government ICT-projects.

Most stories got widespread attention of other media, in some cases the authors were interviewed in radio- and television-shows. Five of the twelve publications prompted questions in parliament and one gave cause to a parliamentary debate. One won a Dutch prize for investigative journalism, one was nominated for the European Press Prize 2015.

The consequences for De Onderzoeksredactie as an organisation were manifold and positive:

- Project subsidies and co-funding by media partners helped raise the budget from € 130,000 to about € 200,000 (an increase of 50 percent).

- It wasn’t necessary to look for potential media & research partners anymore, they started lining up to co-operate.

- The platform, which in the public eye initially was associated with its co-founding partner De Groene Amsterdammer magazine, acquired a reputation of its own.

- The numbers and the quality of applications for the Teaching Lab went up.

- Journalists from outside started offering their services.

When the fist twelve months ended, in April 2015, De Onderzoeksredactie had plans for fifteen big investigations and follow-ups and more than twenty projects with partners. Most of those partners were media but there were also cautious contacts with a scientific medical journal and a research NGO that investigates international companies.

To finance this fast increase in activities, the editor-in-chief (this author) wrote a 5- year expansion plan. Based on that plan, the board asked our philanthropic sponsors to increase both the size and term of their commitment. In June 2015 the principal sponsor announced its intention to quadruple its funding and extend it to three years, for a total of € 650,000 euro’s. This would enable De Onderzoeksredactie to at least triple its budget to about € 400,000 to 500,000 per year and build a more professional and durable organisation.

Conclusion

In the last decade, universities in The Netherlands did not manage to set up a good investigative journalism program. So The Investigative Teaching Lab started as a private initiative of an experienced journalist and a small weekly magazine, on an extremely low budget. This situation had both disadvantages and advantages. Because of the weak initial funding it took time to find and develop the necessary teaching expertise. On the other hand the project had plenty of room to develop its own philosophy and approach.

Developing the program involved permanent evaluations, adjustments and improvements. The team-based approach turned out to be a special challenge and required explicit attention to teambuilding processes. It also took time to develop the dual, qualitative/quantitative methodological core described in this paper, and it is fair to say that this development hasn’t ended yet. However, over the past 4 years the contours of a viable and potentially successful teaching & learning model have emerged.

It was an important move to embed the Teaching Lab in a non-profit organisation for investigative journalism. This offered alumni the chance to continue building up more experience with the team-based approach and the dual core methodology, and to use this experience in setting up co-operations with other media and non-profit research institutes. It also helped in strengthening the financial basis, by attracting project subsidies, co-investments from media partners and additional philanthropic funds. Because of this, De Onderzoeksredactie (The Investigative Desk) was able to grow faster than expected.

To be successful on the long run, The Investigative Desk will have to establish itself as a major, indispensable player in the Dutch media landscape. Furthermore, it has to test and develop its philosophy and team-based model no just on a national but also on an international level, by connecting and working with non-profits and investigative networks elsewhere in Europe and other continents. Only then will it find out whether its ambitions will meet a wider response, whether it can really contribute to the improvement of quality standards and levels in investigative journalism and whether it can develop an interesting and durable business model.

End Notes

- Groen means Green, an Amsterdammer is a citizen of Amsterdam.

- Retrieved 1 October 2015 from http://www.cjr.org/q_and_a/columbia_journalism_school_interview.php and http://www.cjr.org/investigation/rolling_stone_investigation.php

- Jan Blokker (1927-2010) was a well-known Dutch journalist who worked for a variety of national newspapers and as editor-in-chief of the VPRO broadcasting organisation.

- A final version of the new curriculum will be available at the end of this year.

- Retrieved 6 October, 2015 from http://stabilecenter.org/?page_id=12

- Retrieved 24 February 2015 from http://investigativereportingprogram.com/curriculum/investigativereporting-seminar/

- Excluding 3 editors of De Groene Amsterdammer magazine.

References

- Beuving, J. & De Vries, G. ((2015), Doing Qualitative Research, The Craft of Naturalistic Inquiry. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Blokker J. (2010). Nederlandse journalisten houden niet van journalistiek. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker. (2010).Blundell, W. (1988). The Art and Craft of Feature Writing. New York: Penguin Group.

- Davies, N. (2009). Flat Earth News. London: Vintage.

- Den Boer, H. (2011). Vervlechting en ontvlechting. De Groene Amsterdammer, 2011, May 18.

- Engbers, J. (2011). De laatste keer, echt. De Groene Amsterdammer, 2011, May 18.

- Ginzburg. C. (1992). Clues, Roots of an Evidential Paradigm. In: Ginzburg, C., Clues, Myths and the Historical Method (pp. 96-125). Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

- Gladwell, M (2007). Open Secrets. The New Yorker, 2007, January 8.

- Haffner S. (Manuscript 1939, published 2000). Geschichte eines Deutschen,. München und Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

- Lehrer, J. (2010). The truth wears off. Is there something wrong with the scientific method. The New Yorker, 2010, December 13.

- Logger, B. (2011). Creatief met staatssteun. De Groene Amsterdammer, 2011, May 18.

- Pinster, J. (2011). Een Haags bakkie van zeventig miljoen. De Groene Amsterdammer, 2011, May 18.

- Rosenbaum, R. (1998). Explaining Hitler. New York: Random House.

- Sennett, R. (1998). The Corrosion of Character. The Personal Consequences of Work in the New Capitalism. New York/London: W. W. Norton & Company.