This is a research paper that was accepted for but not presented at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference 2017 Academic Track, which IJEC organized and covered. For more research and coverage of GIJC17, see here.

Investigative open data journalism in Russia: actors, barriers and challenges

By Anastasia Valeeva

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford

Abstract

In this study, I wanted to show how open data is used for investigative storytelling in Russia, and what are the barriers that prevent journalists from embracing it. To answer these questions, the study draws on a combination of semi-structured interviews with investigative journalists and open data experts, case studies, and qualitative content analysis. In the final section, I discuss the existing barriers and provide guidelines on how to make investigative data journalism stronger in Russia.

The study revealed that in the emerging eco-system of open data, new actors perform part of journalists’ functions. Politicians and non-governmental organisations use data as a tool to engage with their audiences; civic technology organisations build neutral applications on top of open data and hold it to account; data journalism hackathons provide experimental playgrounds for enthusiastic individuals to work together and investigate official data. However, objective, independent analysis of public data in the public interest, without political ambition or ad-hoc temporary opportunism, is possible only with a newsroom infrastructure that upholds professional ethics.

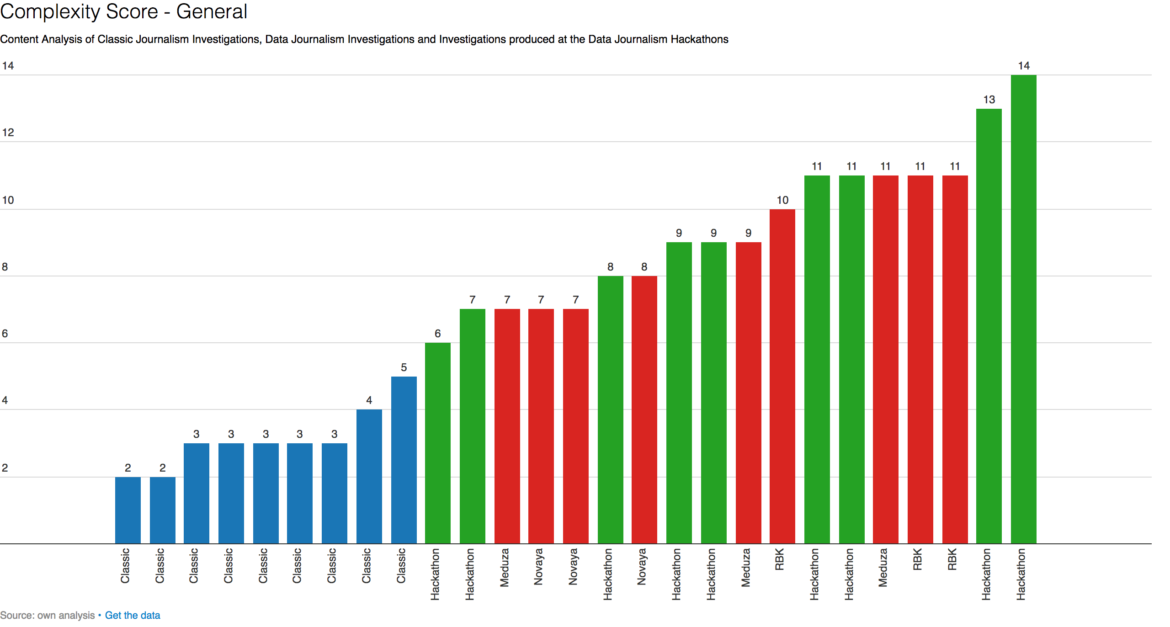

Qualitative content analysis is focused on three different products: traditional investigations, data stories produced at the hackathons, and data investigations published in the news media. Stories are ranked based on complexity of data organization and analysis. The content analysis showed, traditional journalistic investigations are far from embracing data as their information source. Certain newsrooms innovate and have reporters who build their investigations primarily on data. These stories rank high in the organization of data (providing a link and creating a database) and data analysis (search by keywords and statistical knowledge), but low in transparency (access to the database) and use of machine learning. Hackathons serve as an experimental playground, where participants are shifting journalistic culture towards open source and hacker culture.

Introduction

There are many things in common between doing journalism with data and being an investigative journalist. In a way, investigative journalists all over the world were working with government data long before the very term ‘data journalism’ came into prominence. Professional reporters were digging through government statistics, court records and business reports (Howard 2014: 10). These files were, essentially, open data – albeit non-digitised. Today, when data journalism has become a specialisation on its own, there are other clear similarities: both data and investigative journalism are focused on finding new information, both strive for objectivity and work in the public interest. The fact that ‘design of data-processing artefacts can fit the traditional epistemology of journalistic investigation’ has been noted internationally by media researchers (Parasie 2015) and particularly in Russia through the interviews made for this chapter.

But where, traditionally, journalists keep their story secret until the moment of publication, with data investigations they need to loosen control over their narrative in two ways: they should trust data and let it tell its own story, and they should share the content with people from other backgrounds to help with the analysis and presentation. Another distinctive feature of doing data journalism is being transparent about sources and processes, often publishing the data behind the story. This, again, seems at odds with the traditional culture of journalistic investigation. The fact that professional journalists often do not reveal their sources is criticised as a ‘fundamental bug of newspapers’ (Baack 2015: 6).

Apart from these epistemological and professional tensions, there are technical challenges that require investigative journalists to become data savvy to use open data the right way. The essential distinctive feature of open data is that it is ‘typically readable by computers, making it easier for humans to combine and interrogate them’ (Bowles et al, 142). As a result, journalists do not fully embrace open data, staying in their comfort zone, and at the same time, ‘journalists are not seen as end users of Open Data’ (Stoneman, 14) by governments and other actors.

This leads to the fact that in the emerging eco-system of open data, new actors perform part of journalists’ functions. In this study, I want to show how open data is used for investigative storytelling in Russia, and what are the barriers that prevent journalists from embracing it. To answer these questions, the study draws on a combination of semi-structured interviews with investigative journalists and open data experts, case studies, and qualitative content analysis.

In the first chapter I describe the actors who use data for storytelling in Russia: politicians, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and ad-hoc teams of journalists participating in hackathons. Politicians and non-governmental organisations use data as a tool to engage with their audiences; civic technology organisations build neutral applications on top of open data and hold it to account; data journalism hackathons provide experimental playgrounds for enthusiastic individuals to work together and investigate official data. However, objective, independent analysis of public data in the public interest, without political ambition or ad-hoc temporary opportunism, is possible only with a newsroom infrastructure that upholds professional ethics.

In the next section, I focus on the qualitative content analysis of three different products: traditional investigations, data stories produced at hackathons, and data investigations published in the news media. To assess the use of open data in journalistic investigations in Russia, I concentrated on three news outlets:

Novaya Gazeta, an independent journal founded in 1993 and famous for its investigations of sensitive areas such as the conflicts in the Caucasus or human rights abuses;

Meduza, a digital-based news organisation whose core team was formed of journalists who resigned from Lenta.ru when its editor-in-chief was fired in 2014; and

RBC, the biggest non-government media group in Russia which comprises of an informational agency, news portal, newspaper, magazine and broadcast company. It is particularly noted for its investigations into business and politics.

Stories are ranked based on complexity of data organization and analysis using a scoring system. I have measured transparency of journalism by seeing if there was a link provided to the source data; and if the journalist’s own data was put online. Complexity of data analysis is measured by the tools used to produce insight: was it searching for a name in the dataset; performing statistical calculations or running an algorithm? The content analysis showed, traditional journalistic investigations are far from embracing data as their information source. Certain newsrooms innovate and have reporters who build their investigations primarily on data. These stories rank high in the organization of data (providing a link and creating a database) and data analysis (search by keywords and statistical knowledge), but low in transparency (access to the database) and use of machine learning.

In the final section, I discuss the existing barriers for investigative data journalism in Russia and propose guidelines to overcome it. This is followed by a conclusion and bibliography.

- Actors. Who else uses open data for storytelling?

1.1. Politicians like Alexey Navalny

Blogger, lawyer, and opposition politician Alexey Navalny, head of the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK), currently running for the president of Russia, is also a journalist – or, at least, he plays a very similar role. He has been publishing stories about corrupt officials on his personal blog since 2006. In 2010, he has launched the Rospil project (Navalny 2010), the aim of which was to fight corruption in public procurement. Georgy Alburov, head of the investigative unit at FBK, confirms that Rospil has slightly changed direction since 2015:

Before, it was a mechanical analysis of government procurement. Now it’s more about investigations. The analysis of procurement just gave us numbers – how many of the contracts are shady and how much money was lost. This is now not very important for us. What is much more interesting is to make investigations – this means not just finding the presence of corruption in procurement, but describing it and showing the connections between people. This needs more time but has more impact (Alburov 2016).

In December 2015, Navalny published one such story, “Chaika” (Navalny 2015). To use his own words, this was “the main investigation of the year” (Navalny 2015a), in the form of an hour-long documentary and a multimedia story. The story deals with the general prosecutor of Russia or, more precisely, his two sons. Their family name is Chaika. In Russian, “chaika” means seagull, and it is also the title of a famous play by the nineteenth-century Russian dramatist Anton Chekhov. Hence the visual style of the investigation: the theatrical curtain and the subtitle “the criminal drama in four acts”. Through these four acts, FBK tells a story of various corruption schemes and undeclared property of the Chaika brothers. Every claim is documented with the help of data such as land registries and Instagram geotags. What role does open data play here?

To support one of the claims, Navalny and his team downloaded from the official government procurement website all 36 tenders in which the company allegedly belonging to Igor Chaika had participated (Navalny 2015b). They show in an attached table that every time this company participated in a tender, it had the same three competitors – whatever the tender, whatever the region. This indicated a suspicious pattern and a possible affiliation between those companies. When the team looked further, they found out that three companies out of four had the same address, and the other one was registered at the home address of Igor Chaika; besides, they promoted each other’s vacancies on a job site.

This is a classic use of open data in investigations, but is it journalism? Among independent journalists in Russia, views vary: some say “It’s a classic open data investigative journalism. They are the best team in the country today for working with data; not only in their competence and level of analysis, but also in their presentation” (Kolpakov 2016), while others see what they have done as a political activity rather than journalism. “The motivation is the political capital of Navalny, not the public service. But I only care if this is truth, and it is, since it’s backed with open sources and open government data.” (Anin 2016).

The investigative team at FBK admits enjoying another level of freedom and does not deny that they go beyond journalistic standards in their investigations:

We do much of a journalist’s job. But we also do something journalists cannot do. They see that people are thieves and crooks, but they cannot write it. We can. We don’t have any journalistic ethics, we only have internal rules; for example, we do not touch personal issues unless it’s very much about corruption (Alburov 2016).

There is another journalistic standard that FBK neglects: objectivity. It never seeks to provide both (or many) sides of the story, taking a shortcut to accuse a politician of corruption and call for public outrage. This disregard for professional journalistic standards was echoed in the media section of Open Data Day 2017 in Moscow: “the format and the presentation nullify the objectivity, although in its methods of information gathering this is classic data journalism” (Jourhack 2017).

Still, there is something important that journalists could learn from Navalny and his team. It is not just about being active users of data portals and databases, but about employing suitable technology to find the insights. Alburov underlines the importance of technology:

The future of investigative journalism is machine learning for data analysis. We received at least five anonymous messages that one official was buying apartments at a certain address, but we could not identify him. Finally, we downloaded the data for all the apartments in that house, analysed it using machine learning, sorted owners by property, and the biggest owner was our lead. He turned out to be a crony of that official (Alburov 2016).

1.2. Hackathons as a meeting point of state agencies, NGOs, and community(ies)

Navalny’s investigation of the general prosecutor’s family certainly made an impact – it had more than 5 million views on YouTube. It might seem a little surprising in this context that the prosecutor’s office would itself organize a hackathon – a meetup for developers and journalists to work together and investigate official crime data (Genproc, 2016). These hackathons and other initiatives like the All-Russian open data contest and the Open Data Council are healthy signs of a growing open data ecosystem. The Prosecutor General’s office is not the only state agency actively investing in data stories: the Analytical Centre for the Government of the Russian Federation, the Ministry of Culture, Ministry of Finances and the Ministry of Health also take part in the organization and mentoring of journalism hackathons. At these events state agencies find themselves in the unusual company of investigative media such as Novaya Gazeta and the anti-corruption NGO Transparency International. And, of course, there is a growing community of users.

Citizen journalism is developing on a massive scale. See what Navalny is doing, or other bloggers or activists without journalistic education who learn how to work with open data, and make investigations. The FBK branch in St Petersburg is publishing investigations, Transparency Russia, which was never involved in investigations before, has started doing this. There are two reasons for this: open data and active people interested in analysing it (Anin 2016).

So says Roman Anin, investigative journalist at Novaya Gazeta, who attends hackathons as a jury member and teaches students how to work with data in the first master’s course in data journalism at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. His colleague Serafim Romanov, editor-in-chief of Novaya Gazeta in St Petersburg, has started organising hackathons himself, having witnessed growing interest in both data and investigations. He emphasizes that journalists have become full-fledged participants in these hackathons which used to be purely meetups for developers: “Journalists enter the hackathons as storytellers of data. They are needed even though they don’t code.” (Romanov 2017)

In addition, many “non-governmental players are ready to work with data and create applications and websites on top of it” (Begtin 2016). Such products in Russia include a project of Transparency International, http://declarator.org/, which brings together the declarations of officials; a community-run project. https://www.dissernet.org/, which combines manual and automated analysis to detect plagiarism in dissertations; and https://clearspending.ru/, a project of NGO Infoculture which is built on top of the public procurement data, cleaning it and adding more search options. These are technical projects, which provide open data for anyone to use, be it pro-governmental or anti-governmental media or anything in between. As Begtin says, “it’s about creating infrastructure, an ecosystem.”

This is an important development and positive evidence of a growing open data ecosystem in Russia, animated by bottom-up initiatives, with some support from the state agencies. However, it is important to remember that no politician or NGO can substitute for journalists in the role of data storyteller. Objective, independent analysis of public data in the public interest, without political ambition or ad-hoc temporary opportunism, is possible only with a newsroom infrastructure that upholds professional ethics.

- Content analysis of data journalism investigations

Three corpuses of data, each containing nine items, were chosen for this research: data journalism stories produced during the data journalism hackathon that took place in Moscow on 25–26 June 2016; all the investigations published during June 2016 at the website of investigative newspaper Novaya Gazeta; and nine data journalism investigative pieces identified during the interviews for this research as exemplifying best practice.

To evaluate the use of data in every piece and to be able to draw comparisons between them, two methods were used: qualitative content analysis and a scoring system. The scoring system was developed to measure the complexity of data use in the story. It consists of two groups: organization of data and data analysis (see Table 1). A score ranging from 1 to 3 points is attributed for each criterion, with 12 being the highest possible overall score (see the attached table).

Table 1: Scoring system for the complexity of data use

| Group | Criteria | Points |

| Organization of data | Link to data | 1 |

| Organization of data | Creating database | 2 |

| Organization of data | Online access to database | 3 |

| Data analysis | Search by keywords | 1 |

| Data analysis | Statistics (using max, min, mean) | 2 |

| Data analysis | Machine learning | 3 |

The organization of data measures the complexity of getting the data and being transparent about it. If a link to the source is provided, 1 point is attributed; if several datasets are combined for the story, there are 2 points; and if journalists give access to their raw data, this makes 3 points.

Data analysis ranges in complexity from searching the data for specific words (1 point); to performing simple statistical calculations like looking for the best or the worst in the group (2 points); to performing a complex analysis with the use of computers (3 points).

Topic of the story, human story to illustrate the data, and data visualization were the variables measured independently and evaluated during the qualitative content analysis. Data visualization is often referred to as part and parcel of data journalism; however, there is no proven correlation between the number of visualizations or its interactivity and the quality of the story. For this reason, they are not included in the score.

A distinctive feature of the investigations produced during hackathons is the wide variety of topics, whereas journalism investigations traditionally tend to cover procurement or corruption. At the hackathon, four stories out of nine covered health and another two were about sport. In general, the idea behind every story was to understand how a specific part of the system works, from law to implementation: orphan diseases, football legionnaires, the penitentiary system. This is also a source of hidden problems: since the investigation tackles the problem as such, it often lacks a human story from the journalistic point of view. Out of the nine projects, only two had human stories to illustrate the data.

Hackathons produce visualization-rich storytelling: no story had less than three visualizations, the average being seven. Five out of the nine stories had interactive elements in them, sometimes in the form of a game. This high number is not necessarily a sign of quality: some visualizations clearly do not add to the story, and it is hard to adapt interactive infographics for every device. But they are evidence of the active exploration of visual storytelling techniques by the hackathon participants.

As for the complexity score, the majority of teams (seven) created their own database, usually layering two or more datasets together and often (six) they would provide a link to data, but in only one case out of nine did the team provide their raw data for download. On the aspect of data analysis, every team used data for keyword search and statistical calculations. Three teams tried to run an algorithm to produce insights from the data: matching the addresses of prisons with the addresses of contractors on the procurement website; building a model for the number of Olympic medals; comparing the media advertisement of drugs with the number of publications about those drugs in the PubMed research database. This allowed the teams to reach interesting conclusions such as predicting future Olympic winners or claiming that “millions of public funds are spent on drugs of controversial efficiency”.

Overall, hackathon projects score 7 on average, mostly because of their sophisticated data analysis. The highest-scoring project reached the maximum score of 12. To sum up, hackathons provide great opportunities for brainstorming, but “it’s a quick job, whereas investigations take a lot of time” (Romanov 2017). It is also not very sustainable, as the links expire with time: out of 15 stories produced during this hackathon only nine are still online and so eligible to be selected for this analysis.

2.2. Classic journalism investigations

Out of nine stories published by Novaya Gazeta in June 2016, only two use open data in this way or another. To make sure that June was not an outlier month in this respect, another three months were checked for this variable, scoring 3 out of a possible 12. We understand the limitations of this sample due to the time constraints; however, I consider the conclusion that open data is very rarely used in traditional journalistic investigations to be valid. There are several reasons for this. One of them is the sensitive nature of topics investigated: people being killed in North Caucasus, smuggling, corruption and bribery, criminal proceedings, reshuffle at the state agencies. Not surprisingly, a lot of sources are confidential and there is simply no open data on the topic. On the other hand, all stories had an exclusive human angle. Only one story used data visualization, illustrating a smuggling scheme.

However, there are three possible ways in which open data could help here. First, as Novaya Gazeta has a lot of specific knowledge in the sensitive areas of human rights, it could start its own open database and support its great stories with data, pointing out the growing or decreasing trends, or comparing situations across geographical areas. Second, a story could be put into a broader context when layered with other data: for example, a story on the construction of the nuclear burial near St Petersburg could be layered with the ecological data that is available. Third, the data is sometimes hidden inside the story. For example, their story “The Kremlin man” (Novaya Gazeta 2016a) reports on an analysis of the police procurement data which showed that “since Pushkaryov took the post of mayor, the “Vladivostok Roads” municipal enterprise has been recognized as the winner of various tenders 135 times, and in most cases, it was the only participant.” If Novaya Gazeta were to check this data for themselves, perhaps it could give new leads for the story.

The data complexity score for classic journalistic investigations is generally low: the average is 1.5 points for the two stories that did use open data. One of them used a declaration to prove the immense possessions of the official in question (Novaya Gazeta 2016b). Another used open data as the main evidence base. The details are as follows. In the republic of Karelia, in the north of Russia, a tragedy happened in June 2016: 14 children drowned in a disaster at a summer camp. Instructors from the camp took the children out rafting on a lake despite a storm warning. Further journalistic reporting focused on bad conditions at the camp, the negligence of employees, and their previous criminal investigations. Perhaps most alarming is that this was a social summer camp for orphans and children from troubled families, paid for with public funds after a tendering process. The investigation by Novaya Gazeta (Novaya Gazeta 2016c) looked at the public procurement contracts for this summer camp. It compared the description of services on the camp’s website with the description in the tender. They match so closely that it is already a suspicious sign. Moreover, a journalist who studied all the eight tenders that this summer camp had ever won discovered that in all cases it was either the only bidder, or there was one other camp competing which belonged to the same organization. Now, this was a careful reading of the open data about one camp. Would it benefit the investigation and society if we could have a broader view of how the procurement of camps works and flag up suspicious cases?

2.3. Data-driven investigations in Russian news media

In this section, we look more closely at the investigations published in the news outlets Novaya Gazeta, Meduza, and RBC that used data. They were identified during the interviews for this paper as best practices and analysed in terms of their data analysis and the transparency of the process.

Big data investigations at Novaya Gazeta

Novaya Gazeta is a newspaper traditionally known for its classic journalistic investigations. More recently, it has become famous for using big data and leaked databases in their investigations, as well as open sources and open data in their researching. Significantly, Novaya Gazeta joined with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project in publishing the Panama Papers in May 2016 and Russian Laundromat in March 2017. These stories are run by an investigative team headed by journalist Roman Anin.

For my research, I wanted to see how much open data was used in the Panama Papers investigation (Novaya Gazeta 2016). Clearly, it was not the main lead for the story, but it was still used, particularly procurement contracts and declarations. All parts of this series of investigations layered open data with the Mossack Fonseca database. However, the open data was never linked to an original source, nor was the database put online. This is easily explained by the very nature of the investigation, but it is also evidence of the level of ‘openness’ in investigative journalism: it presents the reader with the results without giving access to the raw data.

As for the complexity of data analysis, there were no statistical calculations or special programs employed to establish correlations or discover patterns. Instead, simple ‘fishing expeditions’ were undertaken, searching in the database, for instance, for the names of people close to President Putin. In effect, journalists at Novaya Gazeta were continuing the tradition of old-school investigative reporters when they ‘read’ the data and searched for proof of corruption through various databases, including open data. Visualization of data, in contrast, is where the culture shift happens at the moment: every story had a visualization element to it, and one of them was interactive.

Statistical investigations at Meduza

At the online-first media organisation Meduza, based in Riga, there is no dedicated data group, but there is a team called ‘Razbor’ which in Russian means ‘scrutiny’ or ‘analysis.’ They work with data in a way which is interesting for two reasons. First, they use data to explain complex issues in step-by-step guides often referencing original data or reports. Second, this team also looks for interesting datasets and analyses them – and their reports are then combined with the traditional reporting done by special correspondents. For this genre, they coined the term ‘statistical investigation’.

One of their stories came directly from open data. One weekend, Denis Dmitriev, a member of the ‘Razbor’ team, had some time to look at the dataset published by the Federal Service of State Statistics which had information on the volume of all food products sold within the borders of the Russian Federation during the 2014 fiscal year. The data was available, albeit in pdf form. Having calculated consumption per capita, Dmitriev discovered, surprisingly, that in one remote region of the Chechen republic people consumed more food than anywhere else in the country. Initially, journalists had two explanations – it was either a secret resort for locals or Chechen officials were ‘inventing’ their data.

To check this, Meduza sent a reporter to the region to interview officials and locals. After further analysis of the data, the ‘Razbor’ team found that the same amount of consumption per capita was repeated across half of municipalities in the republic. This was a solid proof that the data was not collected in a fair and adequate manner – even if the total was true, the way it was divided across the regions was artificial. They tried to contact Chechen officials but nobody would pick up the phone (Data Team Meduza 2017). But the investigation had a sort of happy ending: after the new data for 2015 was published, the richest region in 2014 was assessed the poorest one in 2015. This is how data journalism can make an impact in Russia: encouraging officials to pay a little more attention to the data they publish.

As for transparency, Meduza always provides a link to the original data and always creates its own dataset, though still does not give online access to it. In terms of data analysis, journalists employ the basic understanding of statistical analysis, but do not use computer programming to provide the insights. Meduza supports every story with visualisations, but the most important part for them is journalistic reporting.

Open data investigations at RBC

RBC, part of the RosBusinessConsulting media group, has become famous for its investigations in the recent years. In particular, reporter Ivan Golunov built up a reputation for his exclusives based on in-depth work with procurement data and documents.

Golunov not only carefully reads the procurement documents to find the signs of corruption, he also works with the data by sorting, filtering and analysing it. For instance:

RBC has studied all the tenders of the Moscow City Hall under the ‘My Street’ programme [complex improvement scheme for the streets of Moscow planned for 2015-2018]. In 22 out of 31 cases, winners offered a reduction in the initial price in the range of 5.26-5.82 per cent. Of these, eight winners offered the same reduction of 5.2631 per cent (RBC 2015).

These investigations have a distinct data aspect since they analyse tender documents en masse trying to see the bigger picture – who wins most tenders for a project, who are the key players on the market. The link for the original data is always provided, but not for the database the reporter has compiled to draw his conclusions.

As for the data analysis, statistical knowledge is employed to discover the insights, but the algorithms are never used to detect hidden patterns. When asked if his investigation could benefit from developers’ input, Golunov replied that ‘they could automate the work that I am doing manually now’ (Golunov 2017). This, in my view, is an evidence that programmers are not yet seen in the Russian newsrooms as fully-fledged members of the investigative team.

The same applies to designers: at RBC, the use of infographics is more an add-on than an essential ingredient of the storytelling. This is partly explained by the nature of the Russian media where no distinct data teams have emerged yet. But part of the answer lies in the journalists’ determination to keep their control over the storytelling.

Table 2 is a joint table of the complexity scores for all the studied examples. Classic investigations are at the bottom of the list, with hackathons and data investigations competing with each other. Hackathons have both the highest and the lowest results, which is explained both by the ad-hoc nature of the work and the intense experimentation going on at the events. The media are more consistent in the way they work with data: scores repeat across the same news media. But they do not score very high, since they never use machine learning to detect a pattern in the data and never provide access to the database they have created.

- Challenges for stronger data journalism in Russia

Better data

To tell better data stories, journalists need better data in the first place. Whereas in terms of financial transparency Russia competes with frontrunners such as the UK and the USA, there is a crucial deficiency in the areas of social well-being such as health, science, education, crime, ecology. For the data that is available, too often it is impossible to download in bulk. This denigrates the whole idea of ‘open data’ and leaves journalists continuing with their same routine: reading open data manually.

Data literacy

For many journalists in Russia, working with open data means getting information from Russian statistical websites, aggregators and registries. Ivan Begtin, open data expert, comments:

There is a terminological misunderstanding here. We confuse open data with the data from open sources. If journalists use open data, they usually use it in a dispersed way, compiling data for a specific investigation (Begtin 2016).

To harvest the fruits of open data, you need to realise its potential: open data gives an opportunity to work with structured information using digital means. Don’t read the data, analyse it. In this way we can find the hidden stories. Getting people with relevant skills into the team and understanding the added value of their research is essential.

Culture shift in the newsroom: Transparency, presentation, investment

Developers coming from the open source culture can bring a culture shift to the newsroom and push for publishing the data and the source code behind investigations, making it replicable and available for anyone to explore. The same goes for designers who should not simply create illustrations for a story but be co-authors of the investigation, shifting the narrative away from text-only mode.

To implement all these initiatives, investment of time and money is necessary. This is hard when the resources in the newsroom are already shrinking, but change can happen if editors understand the specifics and added value of data investigations.

Conclusion

There is growing evidence of a developing open data ecosystem in Russia, animated by bottom-up initiatives, with some support from the state agencies. However, it is important to remember that no politician or NGO can substitute for journalists in the role of data storyteller. Objective, independent analysis of public data in the public interest, away from any political opportunism, is possible only with a newsroom infrastructure that upholds professional ethics.

Investigative journalism in Russia uses open data at the moment for ‘fishing expeditions’ and picking out pieces of information. Strong investigative units in various media are slowly growing their data literacy, but still prefer to keep text as the main medium of communication controlling the narrative and not sharing with other specialists such as statisticians, designers or developers.

I therefore argue that journalists should work with data in systematic ways and open up their work to colleagues from the other backgrounds. I believe this will empower and enrich investigative journalism in Russia.

References

Arthur, C (2010), Analysing data is the future for journalists, says Tim Berners-Lee, The Guardian, retrieved at https://www.theguardian.com/media/2010/nov/22/data-analysis-tim-berners-lee.

Baack, S (2015) Datafication and empowerment: How the open data movement re-articulates notions of democracy, participation, and journalism, Big Data & Society, Vol. 2, No. 2 pp 1-11

Bowles, N, Hamilton, J. T., Levy, D. A. L. (eds.). (2013) Transparency in Politics and the Media: Accountability and Open Government, I.B. Tauris.

Howard, Alexander (2014) The Art and Science of Data–Driven Journalism, New York: Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Columbia University

Jourhack. (2017). Data Analysis is just the half of the process. Experiences of ‘Vedomosti, TASS and RBK of working with open data’. Retrieved from http://jourhack.tilda.ws/opendataday2017

Meduza (2016) 27 May. Retrieved at https://Meduza.io/feature/2016/05/27/kak-dmitriy-medvedev-manipuliruet-dannymi-o-naselenii-dalnego-vostoka-faktchek

Navalny, A. (2010) 29 December. Rospil. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://navalny.livejournal.com/541417.html.

Navalny, A. (2015). Chaika. [Online investigation]. Retrieved from https://chaika.navalny.com/

Navalny, A. (2015a). 1 December. ‘Chaika. Main investigation-2015 from FBK’. Retrieved from https://navalny.com/p/4573/

Navalny, A. (2015b). Tender Analysis. Retrieved from https://www.dropbox.com/s/qxuxrbvu1i58763/tender%20analysis.xlsx?dl=0

Novaya Gazeta (2016) 3 April. Retrieved from http://krug.novayagazeta.ru/12-zoloto-partituri.

Novaya Gazeta (2016a). 3 June. Retrieved from https://www.novayagazeta.ru/articles/2016/06/03/68821-chelovek-kremlya

Novaya Gazeta (2016b). 1 June. Retrieved from https://www.novayagazeta.ru/articles/2016/06/01/68796-chemodany-s-dengami

Novaya Gazeta (2016c). 22 June. Retrieved from https://www.novayagazeta.ru/articles/2016/06/22/68998-kak-otel-syamozero-vyigryval-auktsiony

Parasie, Sylvain (2015) Data-driven revelation? Epistemological tensions in investigative journalism in the age of ‘big data’, Digital Journalism, Vol. 3, No. 3 pp 364-380

Prosecutor General’s Office of the Russian Federation (2016). 24 October. Hackathon on crime data has taken place in Moscow, with the support of the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Russian Federation. Retrieved from http://www.genproc.gov.ru/smi/news/genproc/news-1131550/

RBC (2015) 19 October. Retrieved at http://www.rbc.ru/investigation/society/19/10/2015/561b6c739a79474587968837

Stoneman, J. (2015) Does open data need journalism? (Working paper). Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Retrieved at http://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Stoneman%20-%20Does%20Open%20Data%20need%20Journalism.pdf

Interviews

Alburov, head of investigations unit at FBK, interview with the author, 28 September 2016

Anin, investigative journalist at Novaya Gazeta, interview with the author, 13 August 2016

Begtin, Ivan (2016) director at Infocultura NGO, interview with the author

Golunov, Ivan (2017) journalist at RBC, interview with the author

Data Team Meduza (2017), interview with the author

Kolpakov, editor-in-chief at Meduza, interview with the author, 10 August 2016

Romanov, editor-in-chief of Novaya Gazeta in St Petersburg, interview on 11 March 2017