This is a research paper that was presented at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference 2017 Academic Track, which IJEC organized and covered. For more research and coverage of GIJC17, see here.

“The more things change, the more they stay the same”: The impacts of social media and digital technology on journalism quality in South African newsrooms

By Findlay, S.J., Bird, W. R. and Smith, T.

Media Monitoring Africa, JHB, South Africa

Abstract

While we continue to grapple with how the processes of news production are changing in the era of digital journalism, what is of even greater significance is how these changes impact journalistic quality. In addition, the ongoing revenue crises experienced by many media houses has meant that one of the few ways to ensure quality investigative journalism is by setting up dedicated investigative journalism units. What does this model mean for existing newsrooms? How has social media and digital technology impacted on newsmaking processes and how have they affected the efficacy and potential for in-depth investigative reporting? We undertook to study the changes to newsrooms brought about by the digital revolution and to understand how these shifts were affecting the quality of news and journalism being produced. We conducted in-depth interviews at three South African newsrooms and examined the media coverage of two critical events over a seven-month period. The research shows that despite diverse media being monitored, common narratives emerged about who was to blame for particular issues. Moreover, the findings reveal how despite technology making journalists’ lives much easier and more efficient on some level – such as the ability to instantly file reports from virtually anywhere in the world and the potentially limitless group of new sources of information – the same kinds of views and voices tend to be put forward and heard. What is clear from this research is that unless clear and deliberate efforts are made to democratize it, media will continue to reflect and perpetuate existing power dynamics and narratives of the powerful. It seems to leave us in the invidious position of increasingly relying on dedicated investigative journalism units for quality investigative journalism, and if this is the case what does the future look like for existing media houses?

Acknowledgement

This research was undertaken by Media Monitoring Africa (MMA) through funding generously provided by Open Society Foundation (OSF).

“The more things change, the more they stay the same”: The impacts of social media and digital technology on journalism quality in South African newsrooms

- Introduction

There can be little doubt that social media and digital technology have fundamentally changed the way in which news is gathered, analysed and disseminated in the modern world[1]. While much evidence reveals how these disruptions have impacted newsrooms from a business perspective (read in most cases: reduced economic and commercial viability[2]), there doesn’t seem to be a lot of research which has examined the quality of journalism being produced in these new systems, nor the impact this has on self-censorship.

Anecdotal reports suggest that the speed and immediacy of our news, as offered through social media networks such as Twitter and Facebook, has critically lowered the quality, diversity and analysis of news coverage across the globe[3],[4]. Here, online audiences consume one-liner news blasts as soon as they are published and faster news updates appear to trump the importance of good quality in-depth analysis. In addition to this, audiences are no longer simply passive consumers of news[5]. They have also become critical sources and publishers of their own news content with the means to add to, amplify or even distort traditional sources of news messages through social networks[6]. With this, many acknowledge the increasingly levels of ‘noise’ that media houses have to compete with in terms of breaking news and analytical pieces[7]. Despite this digital media space, or perhaps because of it, the challenge to maintain ethical, transparent, quality journalism remains as vital to democracy as ever before. Indeed, as Adornato (2012) points out citizens rely on journalists to help make sense of all the information, news and ‘noise’ now available at their fingertips. And as the economic pressures to meet the news demands increase so too does the pressure to place commercial values over news values.

While we continue to grapple with how the processes of news production are changing in the era of digital journalism, what is of even greater significance is how these changes impact journalistic quality and potentially even contribute to self-censorship in the digital media environment. The changing technological environment has allowed for variety of new pressures to develop (accelerated news cycle, fewer resources etc.) and each of these has the potential to fuel a range of behaviour changes in the newsrooms that may ultimately weaken traditional forms of gatekeeping and ultimately undermine the very values of ethical and quality journalism that media attempt to uphold. So our question becomes: where are we now in terms of journalism in the digital age? This research was undertaken to unpack this very issue by attempting to answer the following questions:

- How has social media and digital technology changed the newsroom landscape?

- What challenges are South African newsrooms now facing in light of these changes?

- Have these changes opened up opportunities for unintended shifts in the news agenda?

- How we conducted the research

2.1 In-depth interviews

We interviewed two to three employees at three South African newsrooms to gauge how digital technology has impacted on their news production processes as well as the challenges and opportunities that such changes have brought about for their specific organizations. Three newsrooms participated. Although each newsroom adopts a different approach to social media and technology, active websites, a strong social media presence and the implementation of ‘convergence’ are all standard practice across the three news outlets.

For the purposes of this report, findings and references to both individual participants and/or their affiliations have been anonymised. Three employees at Newsroom A and two employees at Newsroom B and Newsroom C were interviewed. Participants’ roles varied in their respective newsrooms (see Table 1 below).

TABLE 1. Table showing the employees interviewed at the three newsrooms.

| NEWSROOM A | NEWSROOM B | NEWSROOM C |

| Executive producer | Associate editor | Executive editor (and co-founder) |

| Producer/journalist | Production editor | Journalist |

| Senior multimedia producer |

The interviews were conducted in August 2015 and May 2016. The interviews were roughly one hour long, with the longest being 110 minutes. These interviews, although flexible, aimed to address specific questions, including: (1) definitions of good and/or bad journalism, (2) the life cycle of news stories, (3) factors and individuals involved in decision-making processes, (4) influential internal and external pressures facing the newsroom and (5) the impact of social media and technology on newsrooms and journalism. All discussions were recorded and transcribed. Information from these discussions was then used to detail a narrative of each newsroom.

2.2 Case studies

To assess the quality of journalism produced in these news systems, we analysed media content for two major events over a seven-month period in 2015. These were: (1) The Marikana Commission of Inquiry, better known as the Farlam Commission, which was established to interrogate the events around the shooting of 34 miners in Marikana in 2012 and (2) the xenophobic attacks of 2015 which saw foreign nationals being attacked across South Africa. Hereafter the first case study will be referred to as Farlam Commission, while the second will be simply named Xenophobic Attacks.

These events were chosen as case studies as they dominated the media space at the time, both in terms of traditional media and social media. There were also clearly vested interests of different groups involved and these could potentially shape and drive a specific narrative around the events.

We identified all stories, both in print and online, related to the two events. The date range of the two case studies was similar (See Table 2 below). Information from 18 South African media was extracted through specialized online software, Dexter. See Appendix A for the full list of media used. Information from each story was checked and recorded by specially trained monitors at Media Monitoring Africa (hereafter monitors). The data included: (1) name, type and origin of publication, (2) headline and summary, (3) identity of quoted sources (including name, race, gender and affiliation of individuals or groups who were accessed either directly or indirectly in the stories) and (4) underlying key message. The key messages are those that the article implied without stating such outright. By analysing these messages, we can identify the main frame of each article and thereby understand primary media agenda and the overall messaging around such an event. The key messages were identified by clustering the topics selected in Dexter. These topics were clustered according to issues raised and the content found in the news item.

TABLE 2. Media items were extracted for the two case studies between the dates indicated.

| CASE STUDY | START DATE FOR RETRIEVED ITEMS | END DATE FOR RETRIEVED ITEMS |

| Farlam Commission | 5 January 2015 | 10 August 2015 |

| Xenophobic attacks | 4 January 2015 | 11 August 2015 |

2.3 Limitations

In terms of the newsroom interviews, this small sample size (n=3) is certainly not large enough to offer an absolute understanding of the current South African media system. However, the findings from the interviews do provide some important insights into some of the changes and challenges facing South African newsrooms more broadly.

In terms of the case studies, our analysis was restricted to 18 South African media. These media were limited as all analysed articles were: (1) written (i.e. radio and television footage were excluded), (2) available online (to be extracted by Dexter), (3) in English and (4) based in urban centres because of the nature of the South African media landscape.

All monitors received the same monitoring training and followed the same monitoring protocols. Despite these attempts at uniformity and standardisation of results, the possibility of some human error and/or bias cannot be completely eliminated.

- What we found

3.1 How do social media and digital technology change the way news is produced?

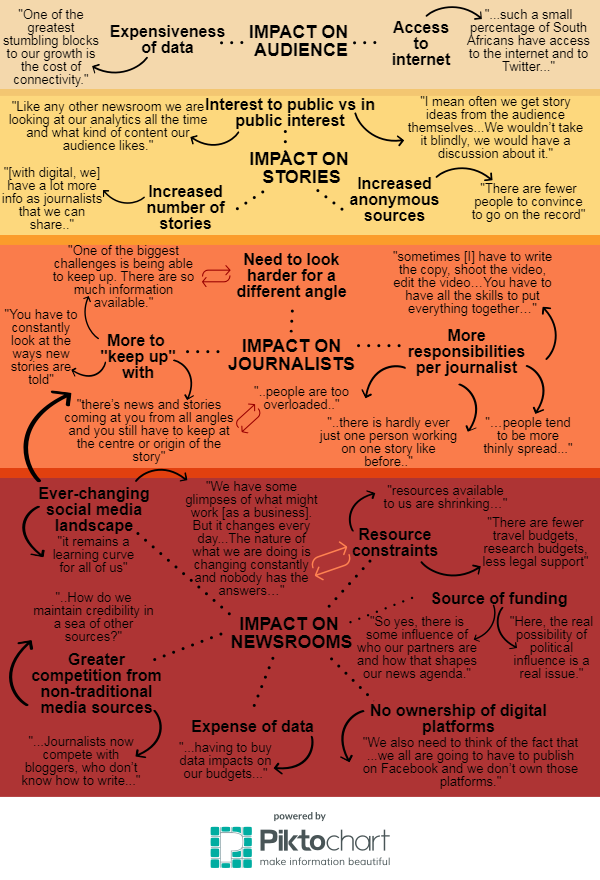

Figure 1 (below) shows the ways in which social media and digital technology have changed the news production process, as identified by the participants. Their ideas were distilled into primary messages and direct quotes are used to support these ideas. Many of the changes were shared across newsrooms.

Figure 1. Ways in which digital technology and social media have changed newsrooms in South Africa, as identified by interviewed journalists. (n=7)

What became immediately clear was that social media impacts the journalists, the audience (consumers of news) and the stories themselves in interrelated but diverse ways. From this, some of the most common changes experienced by those in South African news systems include: (1) the use of social media to source information, stories and leads, (2) better means of telling stories through technology, (3) the accelerated news cycle, (4) greater engagement with consumers (to some extent), (5) greater competition from informal news sources and (6) more information available both to journalists and audience.

One of the most frequently identified changes was the speed with which information and news could be disseminated. Here, many journalists remarked how they could share a lot more content a lot quicker with their audience than previously (Impact on journalist). This not only means that there are now more stories being produced and shared, but also that these stories are often a lot shorter and tend to be less in-depth than previously (Impact on stories). This, in turn, means that there is more news for consumers to ‘sift through’ (impact on audience), which has been seen as both a good and a bad consequence.

This analysis therefore shows the many interconnected and complex ways in which technology has affected all aspects of the news systems in South Africa and this provides the perfect starting point to unpack and identify mechanisms to improve the current state of journalism.

3.2. What are some of the challenges facing newsrooms in light of the changes brought about by social media and digital technology?

It follows that the shifts in news production identified above have also brought about certain challenges to newsroom operations. Figure 2 below reflects some of these.

One of the most common challenges was that of funding and revenue. For all three newsrooms, the impacts of resource constraints were keenly felt. However, it appears that the knock-on effects from declining revenue were most acutely felt by Newsroom B participants, the historically print-only newsroom. Here, participants repeatedly shared how they struggled to achieve an income equivalent to print using only online content. This had led to cutbacks in the newsroom and as a result, staff were overstretched and had less time to do ‘good quality’ stories, follow-ups or stories outside of their primary scope. The idea of “fewer hands on deck” had a marked impact in interviews. This concern over revenue losses and job cuts has been seen across the journalism sector globally[8], and specifically on traditional print media.

The second most common challenge, described in various ways by the three newsrooms, was the sheer volume of information now available online. Interestingly, this was also noted as one of the biggest changes in the news space as described in the previous section. Here, issues around not being able to follow up on all story leads, receiving information that has already been shaped by others as well as the greater competition from new media news sources have all added stress to the newsroom system and journalists generally. Rusial et al. (2015) aptly describe this when they suggest that “[t]he world is in danger of missing the story because of all the noise. And there’s more and more noise”. This struggle of being “able to keep up” was frequently described by the journalists interviewed.

What is clear though is that the changes and challenges described here overlap with each other and often reinforce each other. For example, the impact of fewer available journalists (because of funding issues) is even more intense given the greater amount of online information that journalists need to sort through, the increased number of stories they are expected to produce as well as the greater amount of effort required (“wow factor”) to make the story stand out in a sea of other stories.

Figure 2. Challenges brought about by digital technology and social media in South African newsrooms, as identified by interviewed journalists. (n=7)

3.3 Case studies

While the reflections above highlight some of journalistic experiences around social media and the digital revolution, our question remains: How have these changes impacted on the output and quality of journalism being produced? Has it affected the breadth of events coverage? Has it amplified the range of voices seen in the media? To answer this, we analysed the media content of two significant South African news events.

3.3.1 CASE STUDY 1: How did the media communicate the Farlam Commission (2015)?

The Marikana Commission, also known as the Farlam Commission of Inquiry, was set up to investigate the events that lead to the death of 44 people, including the shooting of 34 miners by the South African Police Service, at a North-West mine in 2012. Although the actual event took place in August 2012, the media analysis below specifically interrogates media coverage of the Commission (not the massacre itself) over a seven-month period in 2015 (5 January to 10 August). 418 articles were retrieved and analysed in total.

Who was sourced in the coverage?

One of the easiest ways of determining who has control of the narrative or whose views and voices are considered valuable is by analysing who gets quoted in the news.

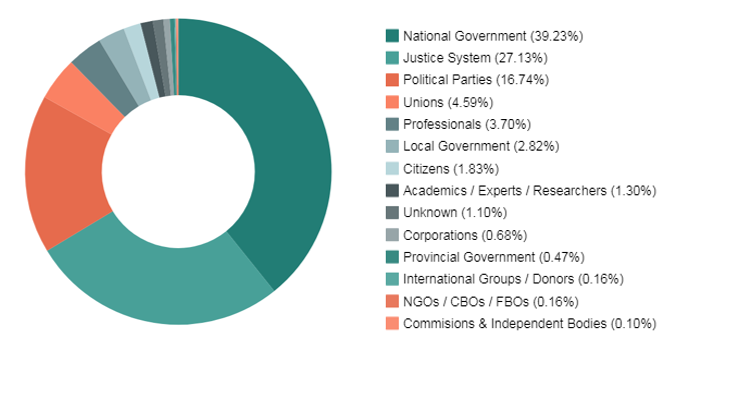

A total of 1917 quotes were recorded in the monitoring period. Of these, National Government (39%), those in the justice system (including lawyers and judges) (27%) and political parties (17%) dominated citations totalling almost over 83% of all article quotes. Other groups including those classified as ‘professionals’, ‘experts’, ‘corporations’ and ‘citizens’ made up less than 5% of all sources. Importantly, this points to an inherent and intense bias towards ‘elite’ sources where citizen’s voices are barely heard.

Figure 3: Sources by affiliation in the coverage of the Farlam Commission.

What was the gender and race breakdown of those who were accessed?

The results of this coverage show a clear preference for male sources (Figure 4). Men constitute 81% of all sources (n=1544) compared to only 17% of sources being female. Within this, the majority of both male and female sources identify as black (84%). Only 1% of all quotes were accessed from Coloured sources and in all of these cases, the sources were male. Other sources including those of an unknown gender, unknown race or those that fall outside of these categories (identified as ‘other’), made up less than 5% of all sources in this coverage.

Figure 4: Gender and race breakdown of sources in Farlam Commission coverage.

What were the main messages put forward by the media?

As part of the analysis, we also pinpointed some of the underlying hidden messages offered in each article. These messages are those that the article implied without stating such outright. 352 of the 416 articles had an identifiable key message. Figure 5 (below) shows the five most common of these. Most of these messages identify an individual or group who should be blamed for the Marikana massacre. Importantly, the most common message was that the unions (in this case, both AMCU and NUMSA) were at fault and were liable for the miners’ deaths. Other stakeholders including Cyril Ramaphosa (Deputy President of South Africa), Jacob Zuma (President of South Africa) and the South African Government were also all directly fingered for their role in the events around Marikana.

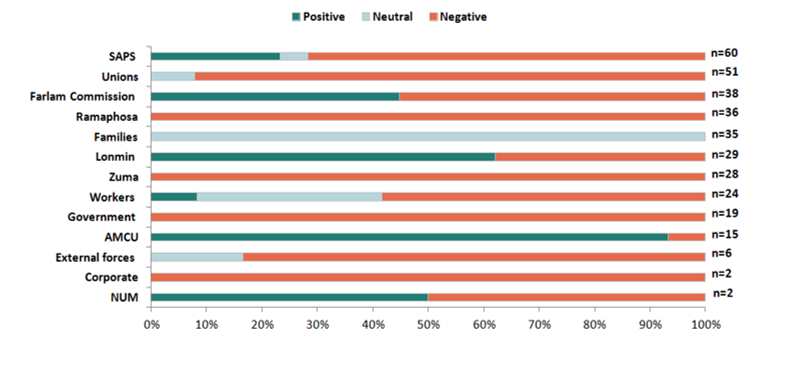

When we break these messages down further, we can also see how different groups are depicted across stories i.e. favourably, neutrally or unfavourably. What is immediately apparent in Figure 6 (below) is that political groups including national government, various politicians, national institutions (e.g. SAPS) and workers’ unions are all portrayed in a mainly negative light. For example, the mainly negative coverage of the South African Police Service (SAPS) stems from the fact that most of the messages either accused SAPS of lying at the Farlam Commission or for their being too impulsive in their use of force at the massacre itself (Figure 8).

Figure 5. 5 most common messages implicit in media coverage about the analysed Farlam Commission.

Interestingly, the only groups to have positive sentiment outweigh negative sentiment were AMCU (Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union) and Lonmin (the company). In these cases, AMCU were seen as genuinely trying to assist the workers and attempting to “peacefully diffuse” the tense situation. Lonmin, who were not mentioned in any of the top 10 most common messages, were most frequently perceived in other stories as “attempting to resolve the strike at all costs” and as “a victim of tragic circumstance”. Given that the Massacre took place at Lonmin and the original cause of the strike were working conditions and wages of which their employer Lonmin plays a critical part, these findings are particularly revealing about who sought to shape the narratives surrounding the Commission. The mention of ‘families’ in this case refer to how families were awaiting the outcome of the Farlam Commission and it was therefore deemed a primarily neutral perspective.

Figure 6. Individuals and groups identified in underlying media messages and the main sentiment directed at them.

Concluding remarks

The analysis reveals a specific position that media appears to have taken in their interpretation of events and the roles of different players in the Commission. We argue here that the messaging clearly blames certain groups for the situation that emerged at Marikana. While the unions were identified as critical players in the massacre, a more important theme is that of self-interest by other political groups. Here, Cyril Ramaphosa, Jacob Zuma and the South African government as a whole were accused of putting their own interests before the interests of the miners. This is a common attitude in much of the media. Interestingly, though, what this also shows us is how a group such as Lonmin, despite being at the centre of such a scandal, managed to gain more positive attention in the coverage than any other party or group. This begs the question: how did the corporate capitalist mine-owners manage to walk away essentially unscathed from such a big event while other groups, including the mineworkers, government and unions, all attract such negative attention? What else is at play here and what impact, if any, has the shift to digital technology played in shaping these narratives?

3.3.2 CASE STUDY 2: How did the media communicate the Xenophobic attacks (2015)?

In early 2015, South Africa saw a flare-up of xenophobic violence across the country which resulted in at least 15 deaths, hundreds of displacements and numerous shops and houses looted. These attacks were carried out by South Africans and were specifically directed at foreign nationals, and most commonly at other African nationals. We monitored all items (n=459) related to xenophobia between 4 January 2015 and 11 August 2015.

Who was sourced in the coverage?

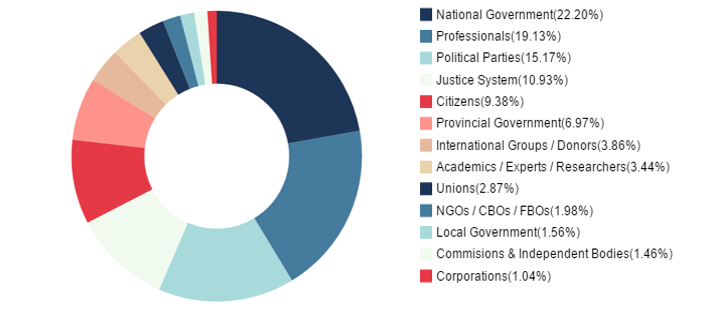

A total of 2,126 sources were recorded during the monitoring period. As we have seen time and again, ‘elite’ sources dominate the voices in this coverage. Here, national government, ‘professionals’ as well as political parties make up 22%, 19% and 15% of all sources respectively. Only 9% of voices accessed are citizens. This is a particularly telling considering that these xenophobic attacks were carried out both by citizens and on citizens.

Figure 7. Sources by affiliation in the coverage of the xenophobic attacks.

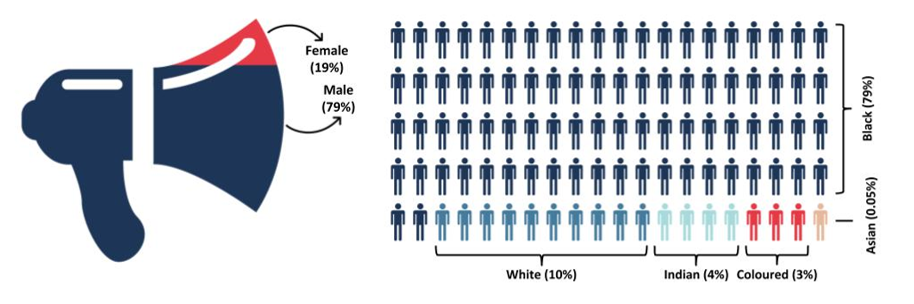

What was the gender and race breakdown of those who were accessed?

The gender breakdown of sources reveals continued biases towards men (79%) in the coverage. Here, women and unknown genders comprised only 19% and 2% of all sources respectively. While this striking imbalance is not new or unique, it does point to the ongoing marginalization and censorship of women across the media and gender bias in the media that is perpetuated globally.

In terms of race, black sources (79%) dominated voices followed by white sources (10%). Other race groups were under-represented at less than 5% of all sources.

Figure 8. Gender and race breakdown of sources in xenophobic attacks coverage.

What were the key underlying messages presented over the seven-month period?

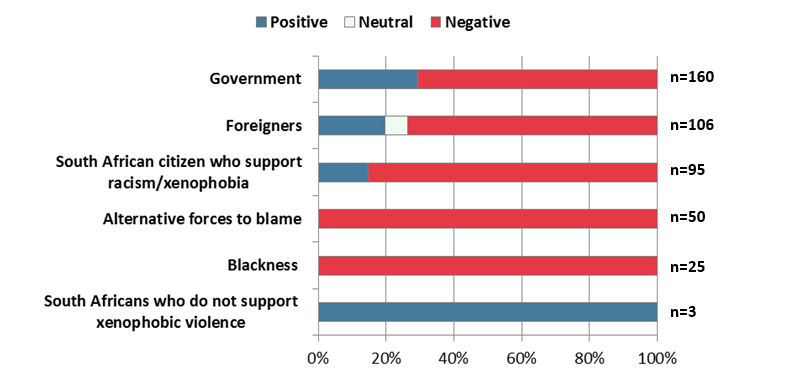

The following aims to unpack some of the implicit messages most commonly seen in the coverage of the xenophobic attacks. The visual below presents the five most common messages.

Much of the messaging in this case focuses on the government. Suggestions that the State both needed to do more in their response (“Government needs to take action”) or that their actions had been sufficient (“State is doing enough”, “State politicians are doing enough”) in relation to the xenophobic violence were regularly put forward in the media. Although these two sets of messages provide differences of opinion regarding the effectiveness of state action, the extensive inclusion of these underscore the perceived importance of government in and around the xenophobic events. Even though the overall sentiment towards government is negative (Figure 10), we argue that the sheer number of messages tend to place the responsibility and outcome of the xenophobic attacks primarily at the government’s feet.

Foreign nationals were also blamed for the violence. Two of the top five most common messages indicate that foreigners “do not belong” in South Africa (33) and that they steal local jobs (23) (Figure 9). These ideas invoke a sense of condemnation towards foreign nationals and seem to suggest that the fault of the xenophobic attacks lies with foreigners themselves rather than with those perpetrating the violence. Here, too, and as can be expected, sentiment about foreigners is primarily negative.

Figure 9. 5 most common messages implicit in media coverage about the xenophobic attacks.

The remaining messages shift the responsibility of the attacks to non-specific groups (“alternative forces”), such as the poor (“xenophobia only happens in poor communities”), or suggest that the attacks were thoughtless and primal in their behaviour (“not more than thuggery”). Even the suggestion that there is “no place for racism in the new South Africa” lays the blame for the violence on a seemingly simplistic understanding of what is driving the attacks i.e. race.

Figure 10. Individuals and groups identified in underlying media messages and the main sentiment directed at them.

In this context, we also identified the idea of “blackness” as a key player in these messages. Here, ideas such as “black governments fail” and “black South Africans are lazy” point fingers directly at black groups or individuals for their inaction and were found in more than 25 articles. In these cases, it was the explicit reference to race that set these messages apart from other identified groups.

Concluding remarks

The messaging and the type of consistent negative framing seen in this case study perpetuates racial stereotypes. These ideas fail to unpack the complexity of events around the attacks, such as the rising discontent and frustration with certain standards of living. This coverage also simplifies the networks of people affected into small vague groups. As we have seen in previous research on xenophobia[9], these ideas undermine the genuine grievances and frustrations felt by those affected, and tend to downplay the motivations for such action to small-mindedness, senselessness and racism. Once again, this coverage speaks to specific agendas which, in this case, are dominated by narratives that are based in racist ideologies.

- So what do the results tell us?

4.1 Media content analysis: what does this tell us about how the news is being produced?

To answer the second part of our objective of what is the quality of news being produced in contemporary news systems, we look to our case studies. What is clear from our analysis is that despite the seemingly drastic changes to the systems in which newsrooms operate and the possibilities offered by technology, the content being produced largely perpetuates historical biases and existing power dynamics. This is seen across both case studies. For example, despite the numerous opportunities that the internet and social media afford citizens to contribute to public discourse (as noted by all newsrooms), it appears that the media remain caught up in accessing ‘elite’ sources. We would expect that the “ease” with which journalists can find sources as well as the closer connection between audience and newsroom, that there would be a greater diversity of people and voices being accessed than previously. However, national governments, political parties and experts all continue to have the loudest voices in the coverage. Citizens, academics and NGOs are all consistently sourced less frequently. Critically, the level of source diversity also points to which groups have the power and ability to influence and shape the narrative being put forward. In both cases, those who were the actual subjects, victims or those who stood to lose the most from the story were those that were consistently accessed the least. By inference, these groups also had the lowest ability to contribute to how the story was reported. Similar findings have been found elsewhere where regardless of the opportunities offered by the digital revolution, historical power dynamics exist and citizens continue to be under-sourced[10]. However, this is also likely to stem from journalistic time constraints rather than from an unwillingness to access on-the-ground groups10.

When it comes to the gender of sources, the coverage of both events illustrates how men’s voices are more readily accessed than women’s. This is despite women making up more than half of the South African population[11]. This type of source bias is seen throughout media research[12]. Likewise, when it comes to breakdown of sources by population group, races such as Indian, Coloured, Asian and other continue to be under-represented. While we recognize the strides made by the South African media to access more voices, this lack of source diversity and the dominance of specific groups reveal how the political and economic elite continue to overshadow other groups.

Bearing the above in mind, we see how specific narratives were carried through the media analysed where specific individuals or groups were held responsible for the events presented. In both cases, very specific ideas about how events unfolded, who was to blame and how effective their efforts were all became clear in our analysis. There were plain and unambiguous narratives being put forward in each case study and importantly, these were largely shared across all the media surveyed here. For example, in terms of the Farlam Commission, much of the responsibility and blame was laid at the feet of political affiliates. Of interest to us was how little attention Lonmin and their board members were given. How did the mining company at the centre of this huge national controversy manage to avoid most of the potential negative press and come out with largely positive media sentiment? Likewise, the coverage of the xenophobic attacks was broadly limited in that it focused only on the roles of government officials and the State as well as on race and “blackness” as the motivations for such activities. Here, the much-needed interrogation of racism and representation of foreigners was almost entirely lacking. This type of reporting remains largely superficial and it fails to move the conversation about xenophobia beyond racial stereotypes. Similar findings have been seen previously on similiar topics[13] which strongly suggests that extensive coverage of an issue does not necessarily ensure an in-depth examination thereof in South African media.

Importantly, and to reiterate, the similarity in messages across all surveyed media speaks to how these narratives are not individually set by newsrooms or even single media houses. Rather they are determined at a much broader level, with tacit and sometimes unconscious support of those in the newsrooms. Our question then becomes: how? How are those that seek to influence the news agenda doing so and how are we getting the news that we are getting? The next section aims to answer this.

4.2 How has social media and digital technology impacted on these systems and how has it affected decision-making processes?

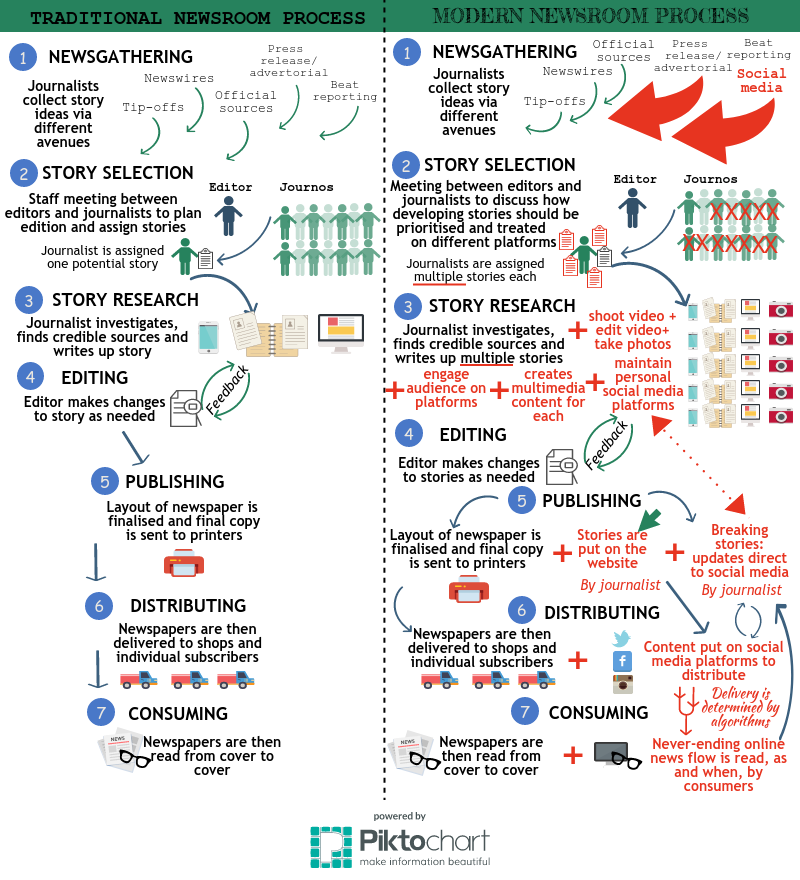

The diagram below (Figure 11) is an attempt to consolidate the complex cascade of changes in the current South African news systems, as noted in the interviews. We appreciate that such efforts are necessarily reductionist in nature but we believe that it provides valuable insights into how the newsrooms have changed and, importantly, offer suggestions into what potential opportunities exist to improve newsroom practices.

It must be stated upfront that the biggest change to modern newsroom production is that it is no longer formulaic nor linear. Rather it is a circular process with multiple and continuous inputs and outputs. Here, the steps do not necessarily follow from 1 to 7 (as seen in the Figure below), but for ease of comparison and to help elucidate in the simplest way how the system has changed, the Figure attempts to provide like-for-like systems. Differently put, the news production process is no longer edition or time slot driven, but is a continuous process of gathering, editing and publishing on multiple platforms. In the process, audience input is also incorporated via social media in follow up stories. So instead of a reporter focusing on one version of one or more stories to complete each day for the paper or evening news bulletin, a reporter works on version after version of the same developing story for different platforms throughout the day, and continuously interacting with sources and citizens.

One of the most striking changes indicated in the shift is the huge and unrelenting pressure on journalists. This stems not only from the fact that there are simply fewer journalists (because of the failing economic models and rampant retrenchments in the sector[14]), but also because of the increased expectations of individual journalists to churn out multiple stories in a quicker turn-around time with more than just written copy (multimedia content etc.). They are also now expected to keep tabs on an ever-increasing volume of potential content through platforms like social media (see big red arrows in right block above). This has critical implications for the quality of reporting being undertaken. Indeed, some studies[15] indicate that journalists struggle to find the balance between the speed-driven nature of modern news with the need for reliability and rigour in their investigations. Often in these cases, reporters acknowledge that the quality of their stories is compromised by the urgency to disseminate it immediately. These findings confirm other research[16] that reveals how some journalists admit to no longer having the time to keep up with “traditional” practices of fact checking, contacting sources and following up on leads. Once again, this could lead to stories that are greatly undermined in their accuracy.

Figure 11. A summary of the changes to the process of news generation between ‘traditional’ newsmaking systems and what we are seeing currently.

The diagram shows the process of news production in a ‘traditional’ newsroom (left) and a ‘modern’ newsroom (right) using key steps (such as newsgathering, story selection etc.) to break down the different elements in the process. The text and figures in red (in the right block) are used to highlight some of the more pronounced shifts observed between the two types of newsrooms.

The incredible time pressure on journalists therefore has the potential to open up wide gaps in the news gathering process and these can be exploited by those with vested interests in shaping the narrative of a specific story, event or issue. In other words, with journalists too constrained to thoroughly examine and verify content, the possibility of them disseminating misleading information[17] or sharing stories that suit a specific agenda is greatly amplified. As Raeymaeckers et al. (2015)[18] point out, prepackaged news content, as provided by external sources, is nothing new in the media space and indeed these products have been used by newsrooms for decades to help them diversify their content. Of increasing concern, though, is that journalists no longer have the resources to scrutinise, interpret and explain the content being delivered to them. For many, they have simply become conduits for PR practitioners and advertisers to deliver material to an eager audience under the guise of news. This is therefore a critical entry point that can be used by those with specific intentions to shape how a story is told and this could also be the reason that narratives of specific events are so similar across newsrooms (as in our case studies).

Importantly, though, journalists are not the only ones facing pressure in these new systems. Editors are under equal strain as they strive to facilitate the production of newsworthy content in an increasingly commercialized media space. This is made even more urgent given the revenue losses in the traditional print industry. In this situation, it appears that newsrooms are therefore pushing for quicker turn-around times for stories in the belief that sharing more online, both in content and speed, translates into more being read and ultimately into more profit being made[19]. Critically, and as has already been noted, this is often at the expense of quality and accuracy and this could be one of the main drivers of the time pressure placed on reporters.

Another challenge to editors, and a potential opportunity to those looking to shape the agenda, is the expectation that stories or ideas “trending” on social media platforms should make their way into the mainstream news schedule[20]. Here, editors are faced with the choice of airing content that appears to be of interest to the public (because it has a high volume of “likes”, “shares” and “retweets”), but that are not necessarily in the public interest, or are even true. The trade-off between what the public are talking about and what they ought to know is now made more obvious given the space that social media now occupies in peoples’ everyday lives. Social media platforms are readily accessible to anyone with an internet connection and this means that, with sufficient time and resources, huge volumes of content about a specific topic or with a particular narrative can be easily circulated by those with vested interests.

Equally important in the discussion around social media is the impact of the actual platforms themselves in the ways in which content is shared among users. Social media algorithms are increasingly a fundamental player in determining how and where information is presented and shared among consumers and their role cannot be underestimated. In these “filter bubbles”, as they have become known, it becomes increasingly difficult for users to access diverse content and this concept of closed circles of information can, no doubt, be used to drive or influence a specific agenda in certain circles.

- Conclusion

There can be little doubt that digital media and the internet have huge potential to transform media, news and information. What is clear from this research, however, is that unless clear and deliberate efforts are made to democratize it, media will continue to reflect and perpetuate existing power dynamics and narratives of the powerful.

The research has demonstrated that despite diverse media being monitored (each of which serve different audiences), common narratives emerged about who was to blame for particular issues. Here, too, the findings demonstrate that despite technology making journalists’ lives much easier and more efficient on some level the same kinds of views and voices are put forward and heard.

We also now see that the initial filters of knowledge (i.e. journalists) are under even greater resource and time constraints to fact check and do justice to stories. Journalists are therefore no longer able to properly fulfill their role as gatekeepers, which, despite the limitations, still remain a critical barrier to outside interference in the newsmaking process. This has therefore facilitated the ability of PR professionals and those with political agendas to impact the narratives of the news.

The real question therefore becomes how can media operate in a way in which the potential of the internet is harnessed to improve quality, independence and transparency of information, while also ensuring that the existing power narratives are shifted and challenged? We believe that this research has served to not only highlight some of the core challenges facing our media and media professionals more widely, but in so doing has also highlighted some of the points of resistance and opportunities to shift power and poor practice. As we take the research forward it will be with the direct aim of seeing what strategies, plans and activities can be developed and implemented to ensure we realize the media necessary for an emerging democracy.

[1] Alejandro, J. 2010. Journalism in the age of social media. Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper: University of Oxford. pp 47.

[2] Franklin, B. 2014. The future of journalism. Digital Journalism 2(3): 254-272

[3] Jones, N. and Pitcher, S. 2015. Reporting tittle-tattle: twitter, gossip and the changing nature of journalism. Communicatio 41(3): 287-301.

[4] Lee, A.M. 2015. Social media and speed-driven journalism: Expectations and practices. International Journal on Media Management 17(4): 217-239.

[5] Russial, J., Laufer, P. and Wasko, J. 2015. Journalism in crisis? Javnost – The Public: Journal of the European Institute for Communication and Culture. 22(4): 299-312.

[6] Adornato, A. 2016. Forces at the gate: Social media’s influence on editorial and production decisions in local television newsrooms. Electronic News 10(2): 87-104.

[7] Adornato, A.C. 2012. A digital juggling act: New media’s impact on the responsibilities of local television reporters. Presented at Annual Conference Electronic News Division. Chicago, Illinois.

[8] Daniels, G. 2014. State of the Newsroom, South Africa, 2014: Disruptions accelerated. Wits Journalism. pp 148. http://www.journalism.co.za/stateofnewsroom

[9] Mtwana, N. and Bird, W. (2006). Revealing Race: an analysis of the coverage of race and xenophobia in the South African print media. Johannesburg: Media Monitoring Africa. pp 43. Access here: http://www.mediamonitoringafrica.org/images/uploads/Final_report_v5_Print_final.pdf

[10] Phillips, A. 2009. Old sources: new b ottles In: Fenton, N. “New media, old news: Journalism and democracy in the digital age”. SAGE: London. pp 87-101.

[11] http://cs2016.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=142

[12] See: (1) Media Monitoring Africa. 2016. “From protest ban to biased reporting? SABC coverage of the 2016 municipal elections”. Johannesburg: Media Monitoring Africa. pp 46. (2) Media Monitoring Africa. 2014. Presentation: “Media coverage of the 2014 National & Provincial Elections in South Africa”. Accessed here: http://elections2014.mediamonitoringafrica.org/ (3) Macharia, S. 2015. Who makes the news? Global Media Monitoring Project 2015. London & Toronto: World Association for Christian Communication. pp 158

[13] Mtwana, N. and Bird, W. 2006. Revealing Race: an analysis of the coverage of race and xenophobia in the South African print media. Johannesburg: Media Monitoring Africa. pp 43. Access here: http://www.mediamonitoringafrica.org/images/uploads/Final_report_v5_Print_final.pdf

[14] Daniels, G. 2014. State of the Newsroom, South Africa, 2014: Disruptions accelerated. Wits Journalism. pp 148. http://www.journalism.co.za/stateofnewsroom

[15] Adornato, A. C. 2014. A digital juggling act: New media’s impact on the responsibilities of

local television reporters. Electronic News 8: 3–29.

[16] Alejandro, J. 2010. Journalism in the age of social media. Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper: University of Oxford. pp 47.

[17] Adornato, A. 2016. Forces at the gate: Social media’s influence on editorial and production decisions in local television newsrooms. Electronic News 10(2): 87-104.

[18] Raeymaeckers, K., Deprez, A., De Vuyst, A. and De Dobbelaer, R. 2015. “The journalists as a jack of all trades: Safeguarding the gates in a digitized news ecology.” In: Gatekeeping in Transition. (ed.) Vos, T.P and Heinderyckx, F. New York: Routledge. pp 104-119.

[19] Lewis, J., & Cushion, S. (2009). The thirst to be first: An analysis of breaking news stories and their impact on the quality of 24-hour news coverage in the U.K. Journalism Practice, 3(3), 304–318.

[20] Adornato, A. 2016. Forces at the gate: Social media’s influence on editorial and production decisions in local television newsrooms. Electronic News 10(2): 87-104.