This is a research paper that was presented at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference 2017 Academic Track, which IJEC organized and covered. For more research and coverage of GIJC17, see here.

Raking Muck and Raising Funds – Capacity Development Strategies for the Future of Investigative Journalism in the Global South

By N. Jurrat, J. Lublinski, A. Mong, DW Akademie, Deutsche Welle

Abstract

In a rapidly evolving technological environment, investigative outlets today face a double challenge: They need to maintain their independence, while also securing their finances. Apart from investigative media outlets and journalists themselves, those who act in support of investigative journalism also need to find answers here: journalism schools need to reconsider how to best prepare young journalists; donors and civil society organizations that fund investigative work need to review their strategies. And the same holds true for international media development organizations which run programs to support media viability, especially in developing countries.

The authors present regional trends from Sub-Saharan Africa, the Americas, and Eastern Europe in light of global developments in investigative reporting, taking into consideration different muckraking cultures, and share examples of successful strategies of investigative media outlets. They suggest that a comprehensive and collaborative approach in supporting investigative media is needed to ensure a viable future for investigative media as well as the sector itself. For this, a model describing elements specific to the viability of investigative journalism is presented to help media startups, donors, media development NGOs identify possible areas of support.

Keywords: Investigative journalism, media viability, journalism education, African journalism, Latin American journalism, Eastern European journalism

Raking Muck and Raising Funds – Capacity Development Strategies for the Future of Investigative Journalism in the Global South

Investigative journalism struggles to survive. This holds true for the United States and Europe, which have a long tradition of investigative journalism. It also applies to developing countries and emerging economies where investigative reporting has only taken roots since the mid-1980s. Freedom of the press in many countries faces severe obstructions. And with the digital media revolution, new finance models and new forms of investigative journalism practice are needed (Albrecht/Hairsine/Leidl, 2015).

The past ten years have seen an upsurge in the setup of so-called investigative media startups — online media outlets run by professional muckrakers who have a passion for editorial independence and journalism as a public good. This came as a result of technological and democratic developments, as well as continuous investment and support for dedicated defenders of investigative journalism in the Global South. In a large number of countries world-wide, this has led to the emergence of a new generation of investigative reporters, who are pushing the standards of the quality of investigative journalism within the entire sector. Many have produced reports that have had an impact at the local, regional, and international level. The importance of investigative journalism is widely recognized (Kaplan 2013; Sullivan 2013). However, many investigative outlets operate on a shoestring and are continuing to face severe obstacles, from legal challenges to physical and digital threats. Overall, the viability of their media outlets and investigative journalism at large is in question.

The aim of this paper is to look at the obstacles and recent trends in investigative journalism in three selected regions: in Sub-Saharan Africa, which has seen a recent upsurge of investigative media outlets; in Eastern Europe, where investigative journalism has been supported by donors and media development actors for almost 30 years, hence offering many lessons learned; and Latin America, where a new generation of investigative startups has been experimenting with innovative digital research, fundraising, and distribution models. The authors will discuss ways in which investigative journalism is currently supported and how these strategies can be improved.

Definitions and Scope of the Paper

There is no universal definition for investigative journalism, not among journalists nor academics, media development organizations or donors. This is also due to the fact that the culture for investigative journalism has developed differently in the various parts of the world. The definitions of Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE) and UNESCO (2013) focus on the unveiling of facts that are of significant importance to the public but that are actively or accidentally hidden, as well as the personal dedication of the journalist to unveil the truth. American authors Ettema and Glasser (1998) as well as Protess et al. (1991:5-7) emphasize the moral aspect and its impact: investigative journalism “probes the boundaries of America’s civic conscience.” By telling “tales of villainy and victimization” it implicitly demands reactions and thus leads to change processes.

African authors have described various problems with the application of the Anglo-American model of investigative journalism, concerns that could easily be transferred to the other world regions: “There are very complicated relationships between the media, civil society, ideas of democracy and power, and processes of social change. Taking this model at face value may stop us from thinking more deeply about those relationships and how they work in our own countries.” Ansell (2010:3, 19) emphasizes that investigative journalism should be an “original, proactive process” which “looks beyond individuals to faulty systems and processes.”

Based on their research and to allow a comparison between initiatives in Eastern Europe, Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, the authors of this paper will explore investigative journalism by looking at four different dimensions. While considering the definitions described above, they will add a new aspect: the interaction with the audience, which has become an important factor for a media’s viability. In the past years, investigative startups have increasingly been using digital and social media to interact with their audience for research and distribution purposes and to seek funds through donations from the public or promote advertising sales. The four dimensions are:

- Content: Investigative reports uncover previously unknown facts, which are concealed from the public or present known facts in a new context.

- Work practices: Investigative journalists need specific qualities and skills to uncover and connect pieces of information and sets of data. Moreover, due to the sensitivity of the information that is being uncovered, organizing the research process and protecting the findings require additional work routines by editors and journalists.

- Impact: Investigative journalism acts as a watchdog for society, exposing how laws and regulations are violated and holding those in power accountable. It aims to trigger change. This can vary from repercussions at a local level to the toppling of a president or forcing nationwide reform to take place. To maximize impact, investigative journalists may actively look for collaborations with other actors in their research or when publishing and disseminating their findings, such as NGOs or the judiciary.

- Audience: Investigative journalists see their trade as a service to society. They may actively involve members of the public when gathering information or to find relevant topics and to support fundraising efforts.

Overall, investigative journalists and editors are facing high obstacles in doing the job outlined above. In many countries it is not possible to report freely and in safety. Journalists who dig deeper are faced with serious threats which are endemic to their respective political, legal, and economic context. “The difference is that while […] in the United States, (journalists) live under the eyes of lawyers, the rest of us in Latin America live under the eye of an AK-47,[1]” describes Mexican journalist and experienced ombudsman Gerardo Albarrán de Alba (2001). While following the journalistic principle to give those investigated the opportunity to comment before a publication usually protects reporters working in countries with a functioning legislature from lawsuits, it can endanger an investigation all together if those in power realize that they are being investigated in countries with high levels of impunity.

Moreover, there has been a loss of trust in the media in many parts of the world (Reboot 2016; Sembra Media 2017), also due to unprofessional practices of some investigative journalists who have misused the term for personal political or commercial purposes or to extort money (Kaplan 2013). This affects all aspects of investigative journalism, especially its potential impact and the engagement with the audience. This, of course, is of great advantage and at times actively promoted by those who have an interest in hiding their political or business dealings from the public.

Nevertheless, professional investigative journalism has been recognized as an effective force for good governance (Kaplan 2013; Sullivan 2013) as well as improving general journalistic standards in a country. Muckraking has hence seen a renewed interest by governmental and private donors as well as media development NGOs (Kaplan 2013; Sullivan 2013; Schiffrin 2017). Digital investigative media have been established with the support of donor funding, producing high quality reports with profound impact. In Latin America, for example, the winners of the 2016 Gabriel Garcia Márquez Award for Journalism in the Americas, one of the most important in the region, were all journalists from media startups[2].

Media viability has become a widely discussed issue, especially since the financial crisis of the global media markets. Overall, technology has offered new possibilities for research and distribution but has also fractured audiences and therefore advertising markets. This has been exacerbated as digital companies such as Facebook and Google are dominating the advertising markets. But media viability is not only about financial sustainability – it encompasses much wider aspects to ensure that a whole media sector may survive (Schneider/Hollifield/Lublinski 2016). It includes the ability to produce independent, high-quality content, an enabling legal, professional and economic environment as well as the organizational capacity within a media outlet to analyze and react to changing advertising, marketing, and fundraising opportunities without losing editorial independence. As local developments, especially digital ones, are changing rapidly, it is important for media outlets to understand the elements that are key for their survival. Only if all aspects are taken into consideration can the viability of any media be supported. And there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Methodology and Research Questions

For their assessment, the authors have applied a mixed-method design, including interviews with a total of 33 journalists, editors, and academics as well as international donors. As part of the desk research, a meta-analysis of evaluations on investigative journalism support programs was conducted. The authors used a selection of eight recent evaluation reports. Half of them are available online[3]; the other half was made available to them confidentially for the purpose of this study.

It should be mentioned that the authors had initially hoped to access a larger number of evaluation reports but no other ones were (made) available. In the support of investigative journalism, monitoring and evaluation systems, although existent, still do not seem to be regularly used to assess and share lessons learned.

Specifically, this research paper endeavors to answer the following research questions:

- What are the trends and potentials for investigative journalism in each region (Eastern Europe, Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa) and where could lessons learned be applied?

- What strategies have been applied in the support of media viability at investigative news outlets so far?

- How can effective strategies for the support of investigative journalism be developed in the future?

- What should be suggested towards the capacity building of future generations of investigative reporters?

Investigative Journalism Culture – Past and Present

Eastern Europe

The investigative journalism scene in the post-communist bloc of countries in Eastern Europe is characterized, on the one hand by internationally acclaimed newsrooms and top-notch reporters— some of the world’s best—and on the other hand by outlets often operating on the fringes of the local media markets, struggling to reach their audiences and achieve the local impact they desire.

This duality is due to several factors, a weak culture of investigative journalism, and more generally the way journalists traditionally understand their role in these societies being among them. In the Soviet-style one-party state which defined all these countries until the fall of the Berlin wall, journalists were far from acting as watchdogs, holding the powerful accountable or serving their audiences. It was rather the contrary. As an integral part of the dictatorial regimes, they were political insiders, directly participating in the decision-making process and influencing it from the inside by providing the forum for a high-level discussion among the political elite (Sullivan, 2013). This tradition is being carried forward, and although it is slowly changing, it still constitutes a major obstacle to investigative journalism: independent-minded reporters often have a hard-time working in mainstream newsrooms surrounded by colleagues, editors, media managers, and owners who continue to understand the role of media along the older traditions.

Moreover, economic conditions for investigative journalism in the region have considerably deteriorated over the last 10 years. The global trend of technological disruption in the news media was made worse by the economic crisis of 2007-2008 which hit these countries particularly hard, having a direct effect on advertising revenues for mainstream news media (Stetka, 2013). As a consequence, foreign investors often gave up their interests, leaving the space to local oligarchs whose primary objective was to exert political influence. In this context, investigations in the mainstream newsrooms are often understood only as instruments to pressure the political elite or discredit and blackmail opponents with Russian-style kompromats.

Against these trends, the region saw considerable media development activities during the 1990s focusing on creating a Western-style investigative journalism tradition and building capacities among reporters (Hume, 2011), who then found themselves more and more in conflict with their surroundings in the mainstream media. As a result, the common trend in these countries since the early 2000s is the creation of non-profit investigative journalism centers, using the latest research methodologies (CAR and data harvesting techniques) and running their own publication channels, mainly on the Internet (Smit et al., 2012).

Some of the world’s most renowned investigative outlets have grown out of this context. First among them is the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), which initially operating only in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, has by now truly global ambitions. It defines itself as an investigative reporting platform with around 40 non-profit investigative centers, scores of journalists, and several major regional news organizations in Europe, Africa, Asia, and Latin America, promoting transnational investigative reporting and technology-based approaches to expose organized crime and corruption worldwide. Another one, also founded in 2005, is the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) whose activities include more than cross-border investigative journalism projects. The network of local NGOs implements a range of programs to promote freedom of speech, human rights and democratic values in the Balkans.

These local and transnational non-profit centers are all almost fully donor-funded and operate in hostile political environments that are increasingly trying to discredit them. Governments in such countries label independent investigations as politically biased activism and the journalists as foreign agents (like recently in Serbia or in Hungary, where the government approved legislation based on the Russian example, requiring NGOs, including journalism organizations to register as “foreign-funded” if they receive grants from abroad). Targeting also is extended to some donors with the aim of scaring them away and drying out the financial support of investigations. Some of these outlets turn to crowdfunding as a way to secure alternative financial resources, although the weak tradition of small donations makes these efforts extremely difficult.

Latin America

Since the region started a transformation towards democracy in the early 1980s, most countries in Latin America have built investigative traditions, often with the support of U.S. and European donors. These traditions were established amidst very challenging environments, characterized by political polarization, violent conflict, organized crime, corruption, and impunity. Year after year, some of the region’s countries have been featuring among the world’s most dangerous places to be a journalist according to the Committee to Protect Journalists—most prominently Colombia and Mexico, where “it is more dangerous to investigate a murder than to commit one” (Knight Center 2017). But even in others, investigative journalists are walking a tight rope between restrictive laws criminalizing defamation, physical and digital threats, and the fear of losing advertising income as punishment for their reporting (Sembra Media 2017).

Nevertheless, there has been an upsurge in investigative digital media in the past 10 years, which are “deeply transforming the way that journalism is conducted and consumed in Latin America …promoting better laws, defending human rights, exposing corruption, and fighting abuses of power’’ (Sembra Media, 2017, p.6). Being laid off from newsrooms at traditional media after the financial crisis or frustrated by restrictive editorial policies at the main media houses that were guided by the media owners’ political and commercial interests, many experienced investigative journalists set up their own online media. Others simply wanted to provide alternative voices in a severely concentrated media landscape. Many of the founders were women, an interesting aspect given the fact that Latin American media is traditionally male dominated (Sembra Media, 2017).

Making use of accessible and affordable distribution technology and cooperating with graphic designers, IT specialists, and even comic artists, a new generation of investigative journalists has emerged in nearly every country in the region, producing high quality in-depth reports on corruption and highlighting the plight of victims of violent conflict or repressive governments. This is a stark development from traditional investigations in the region, where “watchdog journalism” was common place, consisting of simply publishing leaked documents or other information on power abuses based on one or two sources (Waisbord, 2000). More profound investigations were usually published as books. Sharing mostly the same language as well as strong economic, social, and cultural ties enable cross-border collaborations and give investigations the possibility to be published on various national platforms, thereby potentially reaching a huge audience. Most of these startups are funded by international donors, although an increasing number are diversifying their funding and are also looking for financial support from local donors and private persons.

They have increasingly been experimenting with innovative ways to present the often-complex findings and interact with the audience, making long format reporting more attractive (Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas, 2017). One of the many examples is the Big Pharma Project, a collaboration between journalists from six countries in the region, looking into how 13 of the biggest pharmaceutical companies are maximizing profits at the expense of the poorest citizens. Headed by Peru’s Ojo Público (Public Eye), results can be accessed online (https://bigpharma.ojopublico.com) via various formats—video, photos, infographics, written reports, and original documents. It also includes an interactive tool to find out the differing costs of the same medicine in various countries in the region.

Sub-Saharan Africa

The general environment for investigative journalism in Sub-Saharan Africa is far from supportive. Although elementary democratic institutions, such as elections or multi-party systems are in place in many countries, most political and legal systems are still dominated by power elites that control their societies. Media freedom generally remains very limited; many of those in power seek to control the media. Journalists and media houses are being threatened and attacked; self-censorship is widespread (Ismail/Deane 2008, Thomson 2010, Frère 2014). The economic and professional situation in African newsrooms is generally very difficult. Most media houses have limited means and capacities to provide elementary financial and legal support to reporters. Many reporters accept financial support by those who they report on: Brown envelope journalism is commonplace (Rodrigues/Schiffrin 2016, Frére 2012).

And yet, Africa has its own history of investigative journalism. Muckrakers deliver against all impediments their unique services to societies (Schiffrin 2014, 2017). Most cases of investigative journalism discussed in the literature stem from anglophone countries with diverse and strong media markets such as Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, and Uganda (see e.g. Yusha’u 2009, Mudhai 2007, Ansell 2010, Harber/Renn 2010, Reboot 2016). This is also where online investigative media outlets have been established, such as amaBhungane in South Africa, the Premium Times in Nigeria or the INK Investigative Journalism Center in Botswana. There have also been regional initiatives, such as Africa Uncensored, responding to the global trend of crossborder investigations. They increasingly seek to advance transparency and accountability. “In addition to directly holding powerful institutions accountable, media also amplifies the work of advocacy organizations, citizen movements, political organizing, and other accountability efforts” (Reboot 2016).

In francophone Africa, investigative journalism has not developed the same way as in the anglophone part, due to differing media systems and restrictive political and economic conditions. Examples for investigative journalism in francophone Africa are reports from Cameroon, Burkina Faso, and Cote d’Ivoire studied by Lublinski, Spurk et al. (2016). They treat issues like failures in the weather forecast systems for farmers, dysfunctionalities in drug delivery, or the lack of government action against the abduction of women. Here, the reporters were less engaged with the unveiling of secrets and wrongdoings of the powerful. Instead, they acted as change agents who triggered systemic reform processes and built ad-hoc coalitions with NGOs and other relevant actors. These stories were an outcome of the mentoring program SjCOOP (Science journalism COOPeration), which did not have investigative journalism as its primary focus but built a peer-to-peer support network of journalists in Africa. It was run by the World Federation of Science Journalists and was supported by the British Department for International Development and the Canadian International Development Research Center (IDRC), among other international donors.

Across the continent, many investigative journalists perform their research as freelancers or individual activists. One prominent example from lusophone Africa is Rafael Marques de Morais of Angola, founder of the investigative website “Maka Angola”. Over many years, he has fearlessly pointed his finger to the corruption of the Angolan president as well as to the terror which the diamond trade has brought to his country. Even imprisonment could not stop him. Marques de Morais, in a way, is a classic example for muckrakers in Africa and at the same time an exception: As many other investigative journalists on the continent, he works as a freelancer, without the support of a big newsroom and sees himself as a journalist and a human rights activist. Unlike many of his peers, he has received support and Awards for his journalistic work from international organizations, such as the Open Society Foundation and the Committee to Protect Journalists (Rodrigues/Schiffrin 2016) and is well connected internationally.

Generally, African investigative journalism is often supported by development organizations to shine light on a specific developmental issue, such as health. It generally holds true that donor support is of key importance in Africa to make investigative journalism possible. However, investigative media outlets rarely receive seed money to strengthen their overall organizational structure, giving them the opportunity to making them more viable beyond the project cycle.

The experts interviewed for this study observed that African investigative journalists are more and more present at international conferences, not solely as listeners but also as experts, suggesting that there seems to be a global interest in the experiences of investigative reporting in Sub-Saharan Africa. This can also be applied to investigative journalists from other regions in the world. They are in touch with donors and actively use this opportunity to shape the future of their work and the muckraking culture in their respective countries.

Common Obstacles, Trends, and Lessons Learned

While the culture and heritage of investigative journalism differs in Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa, there are several common trends and restraints that they are all dealing with.

Organizational Development and Business Models

Investigative startups as well as investigative teams in traditional newsrooms not only face challenges muckraking itself poses to individual reporters. They also need to (re)organize their work and team structures to meet old and new challenges. As teams grow and staff members with different professional backgrounds working from various locations join the team, new cooperation models need to be considered and established.

At the same time, new, viable business models must be developed. Many media startups have turned to international donors, both private trusts and foundations such as the Open Society Foundations and U.S. and European government agencies, for financial support. The reliance on donor funding, however, remains a substantial risk to their sustainability, even if there has recently been an increase in the number of donors with an interest in media development and investigative reporting (Sullivan 2013, Kaplan 2013) due to the rise of new technologies and the proven impact.

In order to access and manage donor funds, some media outlets have set up fundraising and administrative structures within the media; in others, reporters use their spare time for this, “time that could be spent doing what they do best-investigative reporting,” argues Paul Radu[4], editor of OCCRP. A recent study on Latin American startups by Sembra Media (2017) confirmed that those who did invest in the professionals with these skills have been able to successfully keep their donor base and complement donor funding with other sources of income.

One successful example for the diversification of funding is Atlatszo.hu, based in Hungary, which has managed to raise the considerable share of 44% of their budget through crowdfunding. In Central America, El Faro from El Salvador finances its team of 29 staff through cooperation deals with international agencies (75%), advertising (17%), syndication (3%) and crowdfunding (4%). However, there seems to be a general understanding among the experts interviewed that most investigative journalism will be relying on donor funding for a long time, especially in weak economic markets.

Technology for Investigative Journalism

In Brazil, Agência Pública has been experimenting with storytelling techniques for investigative reports, bringing together reporters, data crunchers, technologists, and graphic designers in so-called ‘J-labs,’ focusing on applying multi-media and technology to journalism. It is part of a general trend in Latin America of using digital technology to present long-format reports in an interactive way, thereby engaging the audience not just by exploring the findings but also for investigative research and topics to cover. In return, this promotion of ownership encourages support from the audience in terms of funding (through crowdfunding campaigns or other grassroots fundraising events) and helps establish a professional culture of investigative reporting, which in turn can be supportive in promoting enabling legal frameworks in the long term.

However, studies have also shown (Kaplan 2013, Robinson/ Grennan/ Schiffrin 2015) that the strong focus on technology has not been able to solve the problems investigative reporters and newsrooms are facing or to promote viability. “Tools and technology are often overemphasized at the expense of strategies that can be just as effective, if not more, at helping organizations be sustainable” (Robinson/ Grennan/ Schiffrin 2015, p. 19). In their report on digital medias startups in Ghana and Nigeria, Reboot (2016, 9) notes that “digital media isn’t a magic bullet, it’s the latest battleground of the ongoing struggle.”

Security

This struggle is based on the difficult political and legal environments in many countries. Intimidation as well as physical and digital violence against investigative journalists are a growing trend. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists[5], most of the reporters that are killed had been investigating politics, human rights abuses, crime, and corruption. A culture of impunity not only denies those attacked justice but also encourages others to use violence and intimidation as a form of censorship. As a result, many reporters turn to self-censorship as a form of personal protection or to prevent their media to be closed down (Jurrat, 2016).

Access to data

In addition, access to reliable data was defined as a problem, even in countries with access to information legislation. In Hungary, for example, the Orban government has introduced fees in order to access specific data, making the assessment of big data sets more difficult. In Colombia, public information is either disorganized or access is denied due to national security reasons, “a concept they are using for everything, even for the CV of the Supreme Court’s magistrates” (Juanita León, editor, La Silla Vacía[6]).

Cooperation

There has been a strong focus by donors on cross-border investigations to increase impact, which has been furthered by the success of the Panama Papers, among others.

While this may take away much needed support for local investigations, it can provide the necessary information to local journalists for their own reports: “Panama-Paper style of investigative journalism and local investigative journalism does not contradict itself — if you start at the grassroots and then go ‘up’ to the powerful,” argues Evelyn Groenink[7]. This is the main mission of the African Investigative Publishing Collective (AIPC) – looking for local stories and then exploring ways that these can be published to an international audience by showing the link to a national interest in the West.

An increase in networking opportunities among investigative reporters and editors, as well as with professionals from the IT, design or research sector, and an exchange of knowledge and experiences has promoted high standards of reporting in all regions and motivated the creation of investigative media startups. Moreover, cooperation between these media outlets has supported joint investigations and consequently the creation of online and offline exchange structures.

Supporting an enabling environment

During their research, the authors noted a recent emergence of support structures for investigative journalism at a local level: J-Labs, such as by Agência Pública in Brazil or Quinto Elemento in Mexico bring together professionals from different sectors to join forces on investigations and experiment with storytelling formats; Quinto Elemento also administers grants for investigative reporting in Mexico; technical support is provided by organizations such as Code for Kenya; Sembra Media offers business advise to media startups in Latin America; and the newly created Platform to Protect Whistleblowers, based in Senegal, is the first of its kind in the Global South. RoGGKenya provides legal advice in plain language to rural investigative journalists in the country.

In addition, an increasing number of fact-checking websites, such as Chequeado in Argentina or CheckAfrica, complement a supportive ecosystem for investigative reporting.

And last but not least, local and regional associations of investigative journalists, such as Abraji in Brazil or the AIPC, are important elements to promote and defend a national culture of investigative journalism and give investigative journalists sustained moral and physical support in an unsupportive and often hostile environment.

Capacity Building

Many media startups are also training journalists in investigative skills —partly to cross-finance their work where trainings are offered for a fee, but mainly to address local demands to improve journalists’ skills and ensure that there are enough muckrakers to look into the many injustices that happen in their countries. Paul Radu notes that “the lack of local capacities is impacting investigative journalism in Eastern Europe. There are a few centers for investigative reporting (…) but there are just a handful of people. What we are able to investigate is just a very small slice of what is going on.” Also, universities such as the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas are offering Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) on topics that are also relevant to investigative journalists and media viability for digital media, from data journalism to product management. These are available to muckrakers from all over the world.

These trainings are filling a void in many places where higher education in journalism is disconnected from the realities of the media industry, especially in the area of investigative journalism, if existent at all[8]. Mark Lee Hunter[9] states that university journalism education is currently often “among the most valueless part of the curriculum in many places,” also because it is hardly ever taught by professors with personal experience in investigative reporting. He suggests that the skills needed to be an investigative reporter could be of value in many other professions and should therefore be taught separately, hence, attracting more talents who might otherwise not consider journalism as a profession. Interviewees from all regions stressed that journalism education, especially investigative journalism, should become more practical and include collaborations with media outlets, big and small, as well as with business and management schools and involve them in the teaching of the craft.

Anton Harber, Adjunct Professor at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg believes that universities should not only be training journalists but aim to foster investigative journalism in a holistic way, thereby helping to create ecosystems for investigative journalism. Apart from its journalism curriculum, the university manages a grant system for individual journalists, hosts a project investigating the justice system in South Africa and offers courses to mid-career journalists on investigative journalism which they can follow while remaining in their newsrooms. Evelyn Groenink, co-founder and investigations editor of ZAM, who has worked in Africa as a reporter and been involved in trainings across the continent since 2003, confirms that “training and capacity building has limited impact if journalists go back to their news organizations and work in an environment where independent investigative journalism is not nurtured or where there are no funds to even pay for the most basic expenses, such as travel.”

Mark Lee Hunter suggests that leadership, strategy, marketing, and basic accounting should be part of the training since future journalists will have to be involved in running organizations, including NGOs: “The idea that investigative journalism is the enemy of business has obscured the necessity for business skills for investigative journalism outlets.” Generally, interviewees identified storytelling and the use of technology for research, presentation, and distribution as the most pressing additional skills needed by future investigative journalists. “Often reporters are good at finding and analyzing data, shooting drone videos, etc., but lack the skills of effectively showing the relevance of their story for their audiences, making people understand why this story is important and how it affects their lives,” confirms Oleg Khomenok[10], investigative journalist from Ukraine, co-founder of Yanukovichleaks and member of the GIJN Board of Directors. However, capacity building has to be tailored to local contexts and possibilities.

Furthermore, there seems to be a strong concentration of skilled investigative journalists in urban centers, which results in the neglect for supporting smaller investigations at the local level. Among the few exceptions are Consejo de Redacción and La Silla Vacía from Colombia, which focus on investigations in the regions and train regional journalists. El Pitazo from Venezuela and the Ground Up News Agency in South Africa aims to provide information on and for the most deprived people in their respective countries. Many local investigative journalists operate without any donor support and often struggle to find handbooks or advice tailored to their circumstances and in their language.

Developing Strategies for Supporting Investigative Journalism

The central finding of our review of the different evaluations of investigative support projects and interviews with experts is that there is a strong need for more strategic planning. Elements that have been considered as good practice within the development community for the past two decades still need to be taken seriously and adapted to the very specific context of investigative journalism support in a particular country. Among them are:

Basic research and needs assessment at the onset. This includes a mapping of the political, legal, and socio-economic situation in the countries in question, an analysis of the situation of freedom of expression and the media landscape with a strong focus on digital challenges. The world of investigative journalism and accountability projects is moving fast and things that worked in the past may be less relevant in a digitalized future. Still, too many projects are developed in the offices of a donor or implementer or by a very limited group of experts. What is needed instead is an intense and sometimes time-consuming consultation process in close cooperation with the partners on the ground, also involving a variety of experts.

A clear theory of change. It very often happens that people involved in a project think they have a common understanding of what it is they want to achieve and what the possible impact might be. In reality these ideas often differ. There are many ways of thinking of change, e.g., as political action, as structural reform in certain sectors, or as developing a new culture of investigative journalism within a media landscape. Consequently, there is a big difference between a project that intends to produce change by supporting journalism schools or investigative startups and one that aims to contribute to anti-corruption processes by giving investigative journalists networking opportunities as well as legal support.

A monitoring system that includes useful indicators. Indicators are not only there to satisfy donors. They should help project managers to focus their attention on relevant issues, involve their partners and keep a project on track. Indicators, if well introduced, can help to see how alumni of journalism schools advance in their careers, show which kind of mentoring models work, identify shortcomings in the research practice of unexperienced reporters and make the case that certain innovative ideas have made a real impact.

A timely evaluation process that stimulates learning. Many evaluations end up in drawers, especially if they are produced after a project ended. Instead, external evaluators should be involved from early onward to capture learning and to find out what worked well and what did not and share the results. Cross-border investigations are a good example: there are well-known international muckraking cooperations that are extremely successful. But there are also indications from the evaluation reports that some transnational support initiatives seemed rather artificial while many reporters preferred to be supported in the pursuit of national stories of relevance to their national audiences. How to best support cross-border work and when not to force it is still an open question that needs to be answered for each context and in close collaboration with local reporters.

The three traditional activities to support investigative journalism — trainings, scholarships and participating at conferences — will, if not supported by more holistic activities, not suffice to prepare investigative journalism for its future. The current challenges the media is facing demand broader strategies to help investigative journalism survive. All this means that broader, long-term support schemes are necessary, where not only investigations into specific topics are being supported on a project base but where the investigative media as a whole is strengthened. This aspect was also emphasized by interviewees from investigative media outlets in all regions.

In the past, we have seen three different kinds of approaches:

- Broad international support programs dedicated to various aspects of investigative journalism. One example, although outside of the regional scope of this paper, is the Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ), which produced remarkable results of supporting individual journalists, the educational system as well as different facets of the investigative culture in the media industry (DANIDA 2013, SIDA 2015). Another is the Regional Investigative Journalism Network (RIJN), which is part of OCCRP. With its focus on the Balkans, Western Eurasia, and the Caucasus, the project promotes investigative journalism through the creation of regional hubs, which support capacity building and story production (USAID 2015). One of the many challenges here is the internal management and organizational development of such a large project while at the same time involving partners on the ground. And the risk of such projects is that those involved only stay among their peers, not leaving their ‘investigative bubble’.

- Promoting investigative journalism as part of a larger journalism support or media development approach. Examples are the “Economic and Political Reporting from Southeast Europe” project funded by the Robert Bosch Stiftung and the Thomson Reuters Foundation as well as the aforementioned SjCOOP mentoring project in Africa and the Middle East, which supported science journalism and investigative journalism. Both projects were very successful in promoting networking and career development of journalists. At the same time, these projects show that investigative journalism is a very special case and that muckraking in different contexts requires very different skills from reporters with other specializations or interests. Hence, such mixed projects need to compromise — or at least match — very different requirements.

- Investigative journalism as part of a larger program towards good governance and citizen engagement. The Rockefeller (2013) Western Balkans program is an example for this approach, bringing together a “civil society triangle” of think tanks, investigative journalists, and grassroots organizations to advance democratic structures. One concern with such projects is that the media — and especially investigative journalism — may be exploited to advance certain topics that donors, implementers, or other partners on the ground would like to see communicated to a broad audience. Here, a dedicated approach is needed that gives investigative journalism the editorial liberty it needs and the support it deserves.

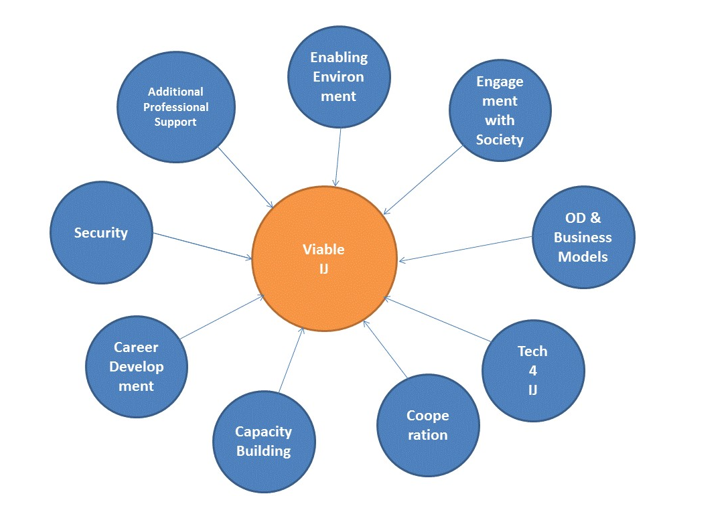

Investigative Journalism Support Model

Based on the analysis of trends and lessons learned above the authors propose the model presented in Figure 1. It describes specific elements needed to ensure the viability of an investigative media outlet, no matter if this is a digital startup or an investigative newsroom at a traditional newspaper. It is intended to serve donors, media development organizations, and media outlets to systematically assess the most urgent needs at a specific time. Media can also use this to identify strategic focus areas for donor support, considering existing skills as well as support that might have already been provided by others. Each aspect should be examined within its specific local context, if possible jointly by the donor or media development organization and the local media outlet.

Fig 1: Investigative Journalism Support Model

The nine different areas (in blue) can be explored as follows. As support mechanisms might cover various viability aspects, they might be listed more than once:

| Viability aspect | Lead questions | Possible support mechanisms |

| Organizational Development and Business Models | What type of processes do we need to manage and change our media outlet? What is a viable business model and how do we implement it? | Consultancy (e.g., on new organizational structures, kick-starting an organization,human resources,fundraising) |

| Tech 4 IJ | What technological tools exist to improve the research as well as editorial management and organization? | Expert consultancy (e.g., exploring or developing technology for the newsroomto (securely) share information, carry out research and analysis, facilitate data journalism, etc.); supporting development of technical services |

| Security | What are the threats against our journalists/editors/the media outlet as a whole? Where do they come from? How can they be anticipated and minimized? | Digital and physical security measures and trainings for journalists and editors, including how to deal with trauma; threat modelling |

| Cooperation | What other journalistic and non-journalistic actors exist who have a shared interest? Where are they? How can we meet them and exchange experiences? | Research collaboration at national level or cross-border; fostering exchange with peers and non-journalistic actors, e.g., at conferences or in JLabs |

| Enabling environment | Which legal, economic and political practices exist that prohibit/ foster investigative journalism? Are there any support mechanisms for IJs in place,e.g. membership associations, regular exchange, etc.? | Consulting and promoting actors to advance the right to access to information, source and whistleblower protection and the decriminalization of defamation; Support IJ Associations, Awards, Conferences as well as supporting actors of independent IJ |

| Engagement with Society | How can we involve our audience and other sectors of civil society to identify relevant topics, conduct research, increase our reach, and maximize impact? Howwould this open uppossibilities for raising funds – crowdfunding, advertising, etc.? Who do we want to reach? | Exploring or developing digital tools for distribution, research, feedback, and fundraising to increase the audience size, income revenue, and impact; strategic consultancy of investigative teams and outlets |

| Career Development | What are the needs of midcareer investigative journalists? How can investigative journalists and journalism overall be supported, nationally and/or internationally? | Scholarships, mentoring programs, awards |

| Additional ProfessionalSupport | What external professional support is needed? | Legal advice, strategic litigation and access to (affordable) legal defense in case of a journalist or media outlet being sued; administrative support; additional research from outside sources |

| Capacity Building | What skills do reporters and editors/teams need to carry out IJ? Are there people from other professional areas that we could train to support our investigations? | Consulting educational institutions on curricula for IJ; trainings, incl. e-learning,handbooks on basic journalistic investigative skills; capacities for editors to manage an investigative team, which may consist of reporters as well as other professionals; training of trainers |

Final Conclusions and Recommendations

The research shows that a more strategic, comprehensive, and long-term approach is needed to support the viability of investigative journalism outlets as well as the sector itself. The proposed model can act as a guide for assessment and the development of a strategic approach. Successful and promising examples to foster a muckraking culture can be found in all regions and should be more widely shared, i.e., via evaluation reports. If this section of media (development) is to be supported in the long term for its impact on good governance, the donor community and media development actors need to invest more in assessing and sharing lessons learned and revise them on a regular basis as situations are rapidly changing. The main recommendations based on our research are:

Funds should be made available to support the organizational development of a media outlet and avoid short-term project funding, which can also question the editorial independence of a media outlet that is already vulnerable to intimidation by those in power. Moreover, seed funding provides the necessary time and flexibility to develop a bespoke fundraising strategy and diversify income sources. For this, professionals with the necessary fundraising and administration skills need to be hired. Support needs to be flexible and adapt to evolving technological and political developments. Moreover, there should be a focus on the capacity building of editors and on the technological development for investigative newsrooms.

Engaging with audiences has been a key element of a successful business model and to ensure journalistic relevance as examples from Latin America and Eastern Europe have shown, promoting ownership and thereby increasing fundraising opportunities.

Capacity building remains still important but various facets need to be considered. While training courses in investigative skills are necessary to raise a new generation of muckrakers, these should be accompanied by mentoring programs and run over several months, not just days. Universities and/or training providers should include modules on basic fundraising, strategy development, and technology for audience engagement in their teachings and ensure that courses include practical aspects, such as internships at digital media outlets and the exchange with local experts. Moreover, the role of universities should be revised as possible facilitators of supportive ecosystem for investigative journalism to prepare and attract the muckrakers of the future.

[1] Translation of: “La diferencia está en que, mientras tú, en Estados Unidos, vives bajo la mira de los abogados, el resto de nosotros, en Latinoamérica, vive bajo la mira de un AK-47″

[2] See https://premioggm.org/ediciones–anteriores/2016/ganadores/

[3] See References below

[4] Interview on September 6, 2017

[5] https://cpj.org/killed/murdered.php

[6] Interview on September 8, 2017

[7] Interview on September 19, 2017

[8] Interview with Rosental C. Alves, July 16, 2017

[9] Interview on September 12, 2017

[10] Interview on August 15, 2017

References

Albarrán de Alba, Gerardo. (2001). Diferencias en el periodismo de investigación en Estados Unidos y Latinoamérica. Razón Y Palabra. Mexico City. http://www.razonypalabra.org.mx/anteriores/n22/22_galbarran.html

Albrecht, E., Hairsine, K., and Leidl, S. (2015): Advancing Freedom of Expression. Using digital innovation to foster Article 19 in the Global South. Bonn: DW Akademie. http://www.dw.com/en/dw-akademie/digital-innovation-study/s-32581

Ansell, G. (2010). Chapter One: What is investigative journalism? Investigative Journalism

Manual. Johannesburg: Jacana. http://www.investigative-journalism-africa.info/?page_id=31 on 23.05.13

Bajak, A. (2017). Eight Interactive Investigative Stories to Check Out. Boston: Storybench.org https://gijn.org/2017/07/10/eight-interactive-investigative-stories-to-check-out/

Buhl-Nielson, E. et.al. (2015). Evaluation of the Swedish development cooperation in the MENA region 2010-2015. Stockholm: SIDA. http://www.sida.se/contentassets/49b982cf56bf4d649ceed9a87bf49524/0994b02a-a331-42d9948e-60c2a090a4c5.pdf

Chapman, J., Dziedzic, M. and Bajrovic, R. (2016). The Rockefeller Brothers Fund’s Western Balkans Program. Midterm Impact Assessment. New York: Rockefeller Brothers Fund. https://www.rbf.org/sites/default/files/attachments/rbf-wb-assessment-report_march-2016.pdf

Coronel, S. (2009) Digging Deeper. A Guide for Investigative Journalists in the Balkans. Sarajevo:

Balkan Investigative Journalism Network. http://www.osce.org/files/documents/1/f/77517.pdf

DANIDA. (2013). Evaluation of the media cooperation under the Danish Arab Partnership Programme (2005-12). Copenhagen: Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. http://www.netpublikationer.dk/um/11210/index.htm

Eijk, D. van (ed.). (2005). Introduction. Investigative Journalism in Europe, 1-30.

Ettema, J. S. and Glassner, T. L. (1998). Custodians of Conscience: Investigative Journalism and Public Virtue. New York: Columbia University Press.

Evenson, K., Brunwasser, N., and de Garcia, D. (2015). Midterm Performance Evaluation of the Regional Investigative Journalism Network (RIJN). Washington: USAID. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00KM3J.pdf

Frère, M.S. (2012). Perspectives on the media in ‘another Africa. Ecquid Novi: African Journalism Studies, 33(3), 1–12.

Frère, Marie-Soleil (2014). Journalist in Africa: A high-risk profession under threat. Journal of African Media Studies, 6 (2), 181-198.

Harber, A. and Renn, M. (2010) Troublemakers. The Best of South Africa’s Investigative Journalism. Johannesburg: Jacana.

Hume, E. (2011). Caught in the Middle: Central and Eastern European Journalism at a Crossroads. CIMA. http://nieman.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/pod-assets/Image/microsites/post-comm/CIMA Central_and_Eastern_Europe-Report_3.pdf

Hume, E. and Abbott, S. (2017). The Future of Investigative Journalism: Global, Networked and Collaborative. https://cmds.ceu.edu/sites/cmcs.ceu.hu/files/attachment/article/1129/humeinvestigativejournali smsurvey.pdf

Hunter, M.L. et.al. (2013). Story Based Inquiry. A Manual for Investigative Journalists. Paris: UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0019/001930/193078e.pdf

Hunter, M.L. et.al. (2016). Power is Everywhere. https://adobeindd.com/view/publications/b83cde7c-df9a-4c44-bc4e001fc0e5200f/l7dp/publication-webresources/pdf/poweriseverywhere2017.pdf

Ismail, J.A. and Deane, J. (2008). The Kenyan 2007 Elections and their Aftermath: The Role of Media and Communication. London: BBC World Service Trust. http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/trust/pdf/kenya_policy_briefing_08.pdf

Jurrat, N. (2016) Media Development in Regions of Conflict, Transitional Countries, and Closed Societies. Bonn: DW Akademie. http://www.dw.com/downloads/35706157/dw-akademiejurratmedia-development-in-regions-of-conflict2016.pdf

Kaplan, D. E. (2013). Global Investigative Journalism: Strategies for Support. Washington:

CIMA. http://www.cima.ned.org/resource/global-investigative-journalism-strategies-for-support/

Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas. (2017). “It is more dangerous to investigate a murder than to commit one”: Journalists confront grave violence in Mexico”. https://knightcenter.utexas.edu/blog/00-18826-it-more-dangerous-investigate-murder-commitone-journalists-confront-grave-violence-me

Lublinski, J. and Spurk C. et.al. (2016). Triggering Change – How investigative journalists in SubSaharan Africa contribute to solving problems in society. Journalism 17(8), 1074-1094.

Mioli, T. and Nafría, I. (2017). Innovative Journalism in Latin America. Austin: Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas. https://knightcenter.utexas.edu/ebook/innovative-journalism-latinamerica

Mudhai, O.F. (2007). Light at the end of the tunnel? Pushing the boundaries in Africa. Journalism 8 (5) 536-544.

Protess, D.L., Cook, F.L., Doppelt, J.C. et al. (1991) The Journalism of Outrage: Investigative Reporting and Agenda Building in America. New York: Guilford Press.

Reboot. (2016). People-Powered Media Innovation in West Africa. New York and Abuja: Reboot. http://westafricamedia.reboot.org/assets/2016_People-Powered-Media-Innovation-in-West-Africa.pdf

Robinson, J.J., Grennan, K. and Schiffrin, A. (2015). Publishing for Peanuts. Public Version. Columbia University School of International and Pubic Affairs. http://www.cima.ned.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/11/PublishingforPeanuts.pdf

Schiffrin, A. (2010). Not really enough. Foreign donors and journalism training in Ghana, Nigeria and Uganda. Journalism Practice, 4 (3), 405-416

Schiffrin, A. (2014). Global Muckraking. 100 Years of investigative journalism around the world. New York: The New Press.

Schiffrin, A. and Rodrigues, E. (2016). Digital Technologies and the Extractive Sector: The New Source of Citizen Journalism in Resource-rich Countries, in Mutsvairo, S. (ed.). Participatory Politics and Citizen Journalism in a Networked Africa. New York: Pallgrave MacMillan.

Schiffrin, A. and Lugalambi, G (eds.). (2017). African Muckraking. Johannesburg: Jacana Media

Schneider, L., Hollifield, A. and Lublinski, J. (2016). Measuring the Business Side: Indicators to Assess Media Viability. Bonn: DW Akademie. http://www.dw.com/downloads/36841789/dwakademiediscussion-papermedia-viability-indicators.pdf

Sembra Media. (2017). Inflection Point. Los Angeles: Sembra Media. http://data.sembramedia.org/download-the-study/

Smit, M., et.al. (2012). Deterrence of fraud with EU funds through investigative journalism in EU. Brussels: European Union.

Stetka, V. and Ornebring, H. (2013). Investigative journalism in Central and Eastern Europe: autonomy, business models and democratic roles. International Journal of Press/Politics, 18 (4), pp.413-435.

Sullivan, D. (2013). Investigative Reporting in Emerging Democracies: Models, Challenges, and Lessons Learned. Washington: CIMA. http://www.cima.ned.org/resource/investigative-reportingin-emerging-democracies-models-challenges-and-lessons-learned/

Sullivan, D. (2016). Want more Panama Papers? Here’s How!, Foreign Policy, 11 April 2016, http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/04/11/want-more-panama-papers-heres-how/

Thomson, A. (2010). An Introduction to African Politics, 3rd edn. London: Routledge.

Yusha’u, M.J. (2009). Investigative Journalism and Scandal Reporting in the Nigerian Press, Ecquid Novi: African Journalism Studies. 30 (2), 155-174.

Waisbord, Silvio. (2000). Watchdog Journalism in South America. News, Accountability, and Democracy. New York, Chichester: Columbia University Press.