This is a research paper that was presented at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference 2017 Academic Track, which IJEC organized and covered. For more research and coverage of GIJC17, see here.

Data-driven journalism: Visualizing the lie versus revealing the truth

By Milagros Salazar, Director of Convoca

Abstract

Journalism is full of data, but not everything is data journalism. There is a difference between using data and establishing a methodology in journalistic research that has, as a fundamental aspect, the organization, analysis and verification of data to find a real story.

But data alone are not enough. It is important to verify them and put a human face on them in order to find a real story to tell your audience. If data are not tested against the situation “on the ground,” there is a danger that they will show us lies, instead of helping us tell the truth in order to help people take better decisions for their lives.

Without a solid methodology built on ethical criteria, the use of database in journalism can lead to bad journalism on a large scale. Therefore, in this paper I describe the trend in the use of databases and their methodologies in journalism, challenges, learning and practices in Latin America. This analysis includes my experience at Convoca, digital media of investigative journalism and data analysis based in Lima, and interviews with journalists from Latin America. Also, the paper examines trends in journalistic projects in the region among nominees for and winners of the Data Journalism Awards, organized by the Global Editors Network and Google, between 2012 and 2017.

Data-driven journalism: Visualizing the lie versus revealing the truth

Introduction

Databases can lie more than people do. But a diligent reporter can detect its lies with the best weapon that journalism has: data verification beyond the computer.

“Without data corroboration, there’s no story, there’s no journalism,” says Paul Radu, Rumanian journalist and founder of Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), a platform dedicated to investigative journalism in Eastern Europe, with a great experience in the work with programmers and data scientists to account cross-border stories.

“The data are triggers of a story and you have to look for a story outside the database. I search for it even in funerary services,” says Sandra Crucianelli, an Argentine journalist known for promoting the use of data in Latin America, to suggest that the information must be confronted even among the dead.

The added value that we journalists give to a database is in what we have always learned: contact with reality, report from the place of the facts and cross information with various sources.

“To completely capture the value of the data, we must be able to distinguish between questionable information and information of quality, and be able to find real stories in the middle of all the noise. The data and technology shouldn’t distract us from our mission for accuracy,” explains the Costa Rican journalist Giannina Segnini, professor at the Columbia University (Verification Handbook for investigative reporting, 2015).

At the same time, the added value that a data base gives to the journalistic work is undeniable: it allows to analyze a wealth of information in a more effective way to look at all the pieces of a puzzle.

“Never before have journalist had so much access to the information. More than 3 exabytes of data – equivalent to 750 million of DVDs – are created every day, and that number is duplicated each 40 months. The global production of data is estimated nowadays in yottabytes (a yottabite is equivalent to 250 trillion of DVDs with data),” adds Segnini.

Therefore, for journalists that investigate, the work with databases has been revolutionary. It has empowered the reporters to find stories on their own and not depend on leaks. It has also allowed to be more convincing to reveal how a system operates, detect patterns of corruption and irregularities, connections and unique cases.

The power of the data has seduced journalists in Latin America in recent years. Every time more often, as it can be seen by the number of journalistic projects with databases nominated in different categories of the most important award of this specialty, the Data Journalism Awards, organized by the Global Editors Network (GEN) and Google.

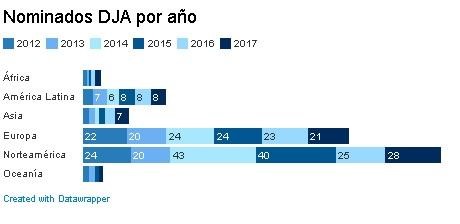

Following the United States and Europe, the work with databases in Latin America stands out. Between 2012 and 2017, 398 journalistic projects have arrived to the final round, and 42 of them (11%), corresponded to Latin America, above Asia, Oceania and Africa, according to a data register built by my colleague at Convoca, Aramís Castro Ramos.

And if we review which journalistic projects are finally recognized with this global award, again Latin America appears in the third place with eight awards, while Asia and Oceania disappear from the list.

Source: Data Journalism Awards. Elaboration: Aramís Castro/Convoca.

Source: Data Journalism Awards. Elaboration: Aramís Castro/Convoca.

“In the last four or two years the work with databases in Latin America has improved; specially, there are more useful projects for the readers and not only focused in data visualization and the fascination for the volume of information,” ensures Paul Radu, member of the jury of the Data Journalism Awards and journalist of the OCCRP, in an interview made for this report.

For Radu, one of the reasons of this growth in the recent years is an improvement of the cooperation between journalists and programmers. “This is important because it’s very useful for an investigative journalist to work with people that work with data every day as the data scientists who can bring a fresh and more specific point of view.”

However, the implementation of data units in the writing rooms is still not sufficient. Sandra Crucianelli ensures that the owners of the media are afraid to invest in works with databases because they look for stories in the short period and aren’t willing to invest resources. In this scenario, there are important exceptions as La Nación newspaper from Argentina and from Costa Rica, pioneers in the use of databases in the continent.

Furthermore, there is an important movement of investigative and depth journalism digital media, created by journalists that bet on the work with databases.

To delve in the evolution of data-driven journalism in Latin America, I interviewed journalists of the region and made a list of learnings and good practices from the contributions of my colleagues and my own experience at Convoca, digital media I founded almost three years ago in Peru to investigate with databases and technological support.

Here is a kind of guide not to visualize lies with databases and tell stories of great public relevance.

- Working with databases begins with a biblical word in journalism: questioning.

“The first rule is to question everything and everyone. There is no such thing as a completely reliable source when it comes to using data to make meticulous journalism,” says Giannina Segnini (Verification Handbook for investigative reporting, 2015).

For that purpose, the Costa Rican journalist proposes five important points we should take into account for the initial verification in the work with databases:

- Verify if the data are complete. A good way to start is to explore the extreme values (highs and lows for each variable in a group of data) and count in the Excel how many rows are listed within each group, to determine if we have all the information. Otherwise, we might come to the wrong conclusion.

- Determine if there are duplicates in the registry of the data in order to eliminate them and have a correct result.

- Verify if the data are exact. For that, Segnini recommends to “choose a sample record and compare it against reality.” Before continuing to work with the database it’s necessary to put it to test from the beginning.

- Evaluate the integrity of the data. Given that the database we usually obtain goes through several stages of “input, storage, transmission and registry” of the information, it’s important to perform tests of integrity. This means, check if it hasn’t been manipulated by people or information systems.

- Decipher the acronyms and codes that were used to classify the data so we can describe the importance of this information and find relevant stories.

- Interview the databases and then confront them

As well as a reporter must prepare to interview a human source, it’s indispensable to know how to interrogate data. There are lot of simple and complex tools and computer programs to organize data and obtain important findings. Among the most used are Excel, Tableau, SPSS and SQL. However, the most important thing, as it happens in any subject we want to investigate, is to aspire to know the database more than anyone.

“Only if you invest a good quantity of hours understanding the structure of a database, it will be possible to interview it correctly and extract significant and juicy conclusions that will become the pillars of a successful project,” points out Hassel Fallas, editor of the Data Intelligence Unit of La Nación, a newspaper from Costa Rica.

Besides understanding the structure of the database, it’s important to know the context of the topic being investigated to detect inconsistencies in the database, mistakes in the digitalization of numbers, repeated names or any other anomaly that leads us to a wrong conclusion.

Once we get the preliminary findings from the database, we must confront the information with reality, go outside and speak with the protagonists of the data. This step can make a difference in the investigation, as we can see in the next cases:

In February 2011, the newspaper La Nación from Costa Rica, with Giannina Segnini at the head, set out to investigate the scholarship award system Avancemos, a program of subsidies to promote that more than 167,000 teenagers continue their studies. As a starting point, the team accessed the database of the beneficiaries and completed it with the name of their parents and crossed them with the information of the goods and incomes of these families. In a first crossing, it was determined that there were tens of scholarship holders with salaries that could reach 9,000 dollars and that also had properties and vehicles inscribed in his name.

However, the story changed when the journalists interviewed these families: the teenagers had parents with economical resources but they had been abandoned.

To arrive to this story, the reporters had to confront the analysis that the database threw in the computer with the protagonists of the story. This way, they could get closer to account what was really happening, give context, find an explanation and not only throw a figure.

Two years later, the team led by Hassel Fallas investigated the student desertion in public high schools. After reviewing the database, with the information of 643 schools, a case that was at the extremes of the ranking stood out: the students leak went from 68% of the enrollment in 2011 to 14% in 2014. It had been reduced by 53 points. Hassel Fallas narrates in his blog The Data Accounts that she sought the principal of this educational center to check the figures, reviewed the documents and confirmed that it was a bad fingering of the figure.

In another school, from 445 students that left classes in 2012, it changed to zero in 2013. Clearly, there was a mistake that was later confirmed by the Ministry of Public Education of Costa Rica.

In an interview with Hassel Fallas for this academic paper, based in the evidences of her work, she pointed out: “Before, during and after the analysis of the database we need to go out to the street to report about how is the life of the people affected by the phenomenon we discover in the data and also to validate this data with sources that help us better understand what it is telling us and why.”

As you can see, the cycle of the work with data ends where every journalist must step on: the street.

- We have to build databases that don’t exist and reveal what is hidden

The majority of databases the Latin American investigative journalists need to narrate stories of great public relevance don’t exist. We have had to create them many times starting from documents, from paper.

To extract data in an automatized way from these documents, an Optical Character Recognition (OCR) program can be used only if the format allows. And in other cases, the majority of times, we will have to build them manually because the documents delivered in the information requests to the State, are almost always delivered in not accessible formats.

Hassel Fallas makes a list of the obstacles that exist to access to the data to find a journalistic story:

- Data in PDF or Word format

- Pictures of data in PDF

- Spreadsheets locked with a password

- Data in program formats that require a license

- Data without structure

- Incomplete data

- Refusal by the authorities to provide us with complete databases. In several cases, we are only offered to make specific crossings, which prevents us from seeing the whole data.

- Negative to supply the database when available in an online search engine. This leads us journalists to create an automatized extraction method to systematize them into a database with the help of system engineers even though the State has the information.

At Convoca, the digital media of investigative journalism and data analysis that I run from Peru, we had to manually enter to a spreadsheet hundreds of data from the sworn statements of property and income of the 130 congressmen of the Republic.

After more than two years of repeated requests of information to the General Comptroller of the Republic, we obtained the documents but in a JPG format (images), which made impossible to pass the files through an OCR program.

With the information, we decided to build a database with a team integrated by journalists with experience and young university students who were capacitated by us in the use of these tools and the work process with databases.

We soon discovered that in the sworn statements there was partial and doubtful information, not corroborated by supervisory bodies. If the information was doubtful, why build a database with these papers? Because those were official documents considered by the authorities as an effective tool to fight corruption and assets laundry. Therefore, it was of high public interest to know and show the lie.

The construction of the database and the process of verification allowed us to identify the patterns of error, omission, fake data and inconsistencies that appeared in the sworn statements of the politicians.

For that reason, it was indispensable to cross information with the public records of assets and companies, to visit properties and to access to other sources of information.

One of the stories we published in the elections of 2016 in Peru as a part of an investigative series we called Patrimonio S.A. (See the project: http://www.convoca.pe/especiales/patrimonio-sa/), was the one of the then legislator Joaquín Ramírez, former general secretary and financier of the party Fuerza Popular of Keiko Fujimori, who was leading the surveys in those elections.

As a part of the verification process of the sworn statements we could demonstrate that Ramírez hid, corrected and increased the number of properties at his name and through his companies.

Ramírez corrected the amounts from the property item of all the affidavits he gave to the Administrative Office of Congress since he became a legislator in 2011. In addition, there was an increase in millionaire purchases of goods through his companies when he began to exercise the parliamentary function. The acquisitions were concentrated in 2012, precisely when Ramírez concealed in his sworn statement of that year properties that never ceased to be his (See the investigation: http://convoca.pe/investigaciones/el-patrimonio-disfrazado-del-financista-de-keiko-fujimori).

In this case, it was important to show through the reportages the lies consigned by the congressmen in the documents and to make information of the sworn statements accessible for the citizens through a news application, as an exercise of effective transparency and contribution to public inspection. Not only to know more about the politicians, but to know about the information failures of these public documents that, supposedly, should contribute to prevent corruption in the State. See the News App: http://www.convoca.pe/especiales/patrimonio-sa/rastreadorpolitico.

- To look always deeper: cross the databases and ask powerful questions to generate impact

How deep do you want to get with a story? That is a fundamental question that we journalists must ask when starting an investigative project with databases.

“Often, a database alone doesn’t include all the variables we need, then we join them with others to widen the context,” ensures Hassel Fallas.

The crossing of the databases allows the reporter to generate powerful investigative series with rigor, precision and effectiveness in the search for information to generate knowledge.

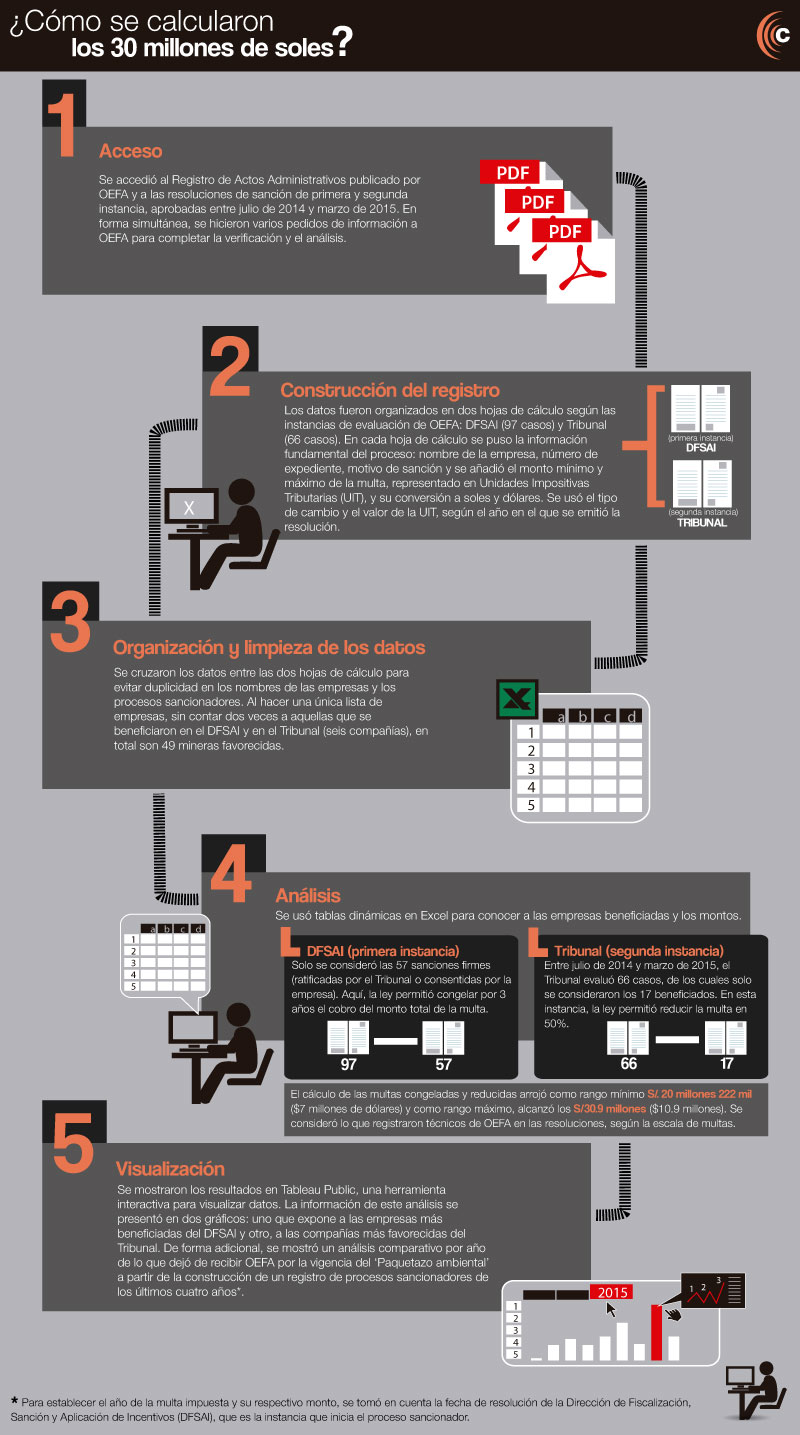

In the middle of 2014, Convoca started to build a database to measure the degree of accomplishment of environmental rules of the great mining and the oil industry in Peru because of the increasing number of social conflicts generated in the country for the execution of these projects and at the same time it’s about activities of great importance for the Peruvian economy.

Regarding the relevance of the topic, there was no doubts. The big question was: What do we want to tell? Giannina Segnini, who is a member of the committee of advisors of Convoca, helped us to land the hypothesis: the companies relapse one and over again on the same infractions because they prefer to be fined rather than invest in the improvement of their productive processes not to damage the environment and the health of the people who live in the surroundings of mining projects. These companies even prefer to pay to law firms to freeze the payment of the fines in the Judicial Power.

Telling that story resulted more powerful that just accounting the number of fines and infractions that each company had and knowing which ones were the most infringing.

For the project, we had to create other databases with information from documents and other sources to deepen our findings. For example, to determine how many million dollars the Ollanta Humala government forgave in fines to the mining and oil infringing companies through the approval of the article 19 of the 30230 Law that was approved in July 2014 in the middle of interest conflict. The work with databases, information crossing and reporting, allowed us to determine that there were more than 17 million dollars forgiven in fines, despite the government inspector collected evidence of the infractions.

Other databases we built allowed us to detect the business and political relationships of these companies to determine the influence ability of business groups in the political power. Other spreadsheets built with the information of hundreds of documents helped us to determine that there were more than a thousand supervision reports linked to corruption cases and of great political influence kept under the carpet.

This project we called ‘Excesses unpunished’ won the Data Journalism Awards 2016 in the News App category, given by the Global Editors Network and Google, and it was finalist in the Innovation category in the Gabriel García Márquez Ibero-American Prize.

But the bigger impact was that, after two years of publishing our reports about the topic in a permanent way, the Congress derogated the article of the law that forgave the environmental fines taking as a base the evidences revealed by Convoca.

For this investigation, we crossed 14 databases built from thousands of documents obtained through more than 100 information requests to the Peruvian State and other sources. The registry of the data we built became a fundamental source of information to publish a series of reportages during two years until achieving a public impact.

A similar effect occurred with the investigative series ‘Pesca negra’ I published with IDL-Reporteros between 2011 and 2013, which showed the underwriting of the massive and millionaire anchovy fishing in the Peruvian sea, the second most important fishing nation after China.

The lack of state control allowed that, in a little less than two years, 630,000 tons of anchovy, valued in approximately 200 million dollars, disappeared from any state control.

For this investigation, there were processes more than 200,000 documents of fish landing, which were linked to a big database through an algorithm. A part of the database had to be built entering data by data.

In a first stage, the work was made with the participation of the system engineer Miguel López and then the investigation was expanded with a collaborative work with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ).

After two years of permanent publications, this series of reportages made it possible to generate a reform in the fishing sector in Peru.

The research with databases allows to narrate in many deliveries a great story, give following to a topic and contribute to generate changes.

- Follow the data beyond the borders

The crimes of corruption, money laundering and organized crime know no borders. The journalistic investigation with databases allows us to travel different countries to follow the money track and the felonies with a collaborative work. The internet and technology make possible nowadays the existence of global writing rooms as the one led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) with the global project Panama Papers.

This global investigation became a powerful referent to promote the collaborative work because it involved around 400 journalists in the world.

The reportages were developed mainly from the search of information in more than 11 million documents from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca to reveal opaque financial practices, evasion cases, tax evasion and money laundering by setting up offshore companies in tax havens.

Though the main source of information wasn’t a structured database, many teams of journalists built their own spreadsheets to cross them with other databases in each country and find good stories.

In Latin America, four teams of journalists from an equal number of media narrated for the ABCDatos publication of Convoca that they counted with programmers in their teams to develop their investigations. Between them were the journalists from La Nación newspaper from Argentina, one of the pioneer media in the use of database in the continent.

“We did a manual labor (registering the names of all the Argentinian characters) while the engineer tried to cross our databases with the new findings we obtained from the Panama Papers,” explained Iván Ruiz (ABCDatos, 2015).

Ruiz considers fundamental the previous experience that his team acquired in the projects Swiss Leaks, Offshore Leaks and Luxemburg Leaks of ICIJ, to find relevant stories for Argentina.

Following the ICIJ model, Convoca initiated the collaborative work Investiga Lava Jato along with journalists from Folha of Sao Paulo, to develop reportages and build databases about the enormous case of corruption Lava Jato, with the participation of more than 20 colleagues from media of Latin America and Africa.

Between the allies appear the newspaper Perfil from Argentina, the investigation portal Mil Hojas from Ecuador, El Faro from El Salvador, Plaza Pública from Guatemala, the organization Mexicanos contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad, Colombiacheck, the Regional Initiative for Investigative Journalism in the Americas of ICFJ/Connectas, the portals Runrunes and El Pitazo from Venezuela and the Jornal Verdade from Mozambique.

To investigate the corruption network of the Brazilian companies requires a cross-border, collaborative, persistent and effective work in terms of evidence and time. For that reason, we joined efforts to develop and publish reportages, to share relevant information about our countries where Odebrecht confessed to have paid around 800 million dollars in bribes, to learn from the process of investigation with methodology and perseverance as well as to bring light over the corruption patterns, what is kept hidden or what is half-told in the public sphere.

Our first joint investigation was published in June 2017. The series of reportages revealed that in seven countries where the Brazilian company Odebrecht paid bribes to officials and intermediaries, 50 works executed by the company under different modalities of contract, investment and concessions, had additional costs for more than 6 billion dollars in relation to the initial values between 2011 and 2016. This finding was possible with the collaborative construction of a database of the works from the contract, police documents, court documents, other databases and various sources.

The data analysis took us to investigate and arrive to other findings. The majority of the increments of budget were by extensions of terms, additional works and engineer alterations, that in many cases are under investigation by the justice. These extra operations didn’t pass through public contests and were kept in hands of the Brazilian constructor and their partners through repeated modifications in the contracts or special regulation that skipped the laws of recruitment.

From this number of works with budget breaks in Peru, Panama, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, Colombia and Mozambique, 31 are being investigated by the Public Ministry or the Contraloria of these countries. This means 61% of the total number. Also, seven of these works, 23%, appear in the forms of the Odebrecht Structured Operations Division, known as the “Office of Bribes,” according to the analysis of more than 8,000 documents made by the journalists of ‘Investiga Lava Jato’ until June 15.

Reviewing the documents of the Brazilian justice also allowed us to know other new stories of bribe payments in Mexico, Venezuela, Argentina, Peru and Mozambique.

Each journalist gave their talent and ability to the service of the project. Some members were focused on the construction of the database with the assessment of the Convoca team, the collaboration of Clomobiacheck, and other journalists were focused on the access to documents and human sources.

Also, the simultaneous publishing of the stories in a project of this dimension, protects the findings of the reporters before the pressures or the existence of “a propagandistic device to hide” and maintain impunity in Latin America in front of corruption, ensures the journalist Sandra Crucianelli.

Working in a collaborative way requires to develop a dynamic of horizontal work and put to the service of the project the best of what one we knows to do best. The result: revealing stories.

- Apply the methodology with rigor and be transparent with our decisions.

To dive in databases, organize, clean, interpret and confront them is part of a method that the reporter builds to arrive to determined journalistic findings. This process must be done with rigor and knowledge about the reality in order to tell real stories.

The Colombian journalist and editor of the Data Unit of El Tiempo newspaper, Ginna Morelo, points out that in the methodology the journalists build is essential the reporting, which has as a purpose to “standardize data” to decipher why some phenomenon and facts of public relevance occur.

“Journalism always -since its origin- has searched for data. Before, the problem was where to find them; today the matter is to standardize so many and interpret them and that takes on great importance because it lets us arrive to more complex patterns regarding why and what for facts occur,” she says.

A case that sets an example to the importance of methodology is the cross-border investigation “Niñas Madres,” a radiography of the causes and consequences of teenage pregnancy in five countries of Latin America that reveals one of the faces of inequality in the continent. In this project, participated the journalists of Convoca from Peru, Nómada and Plaza Pública from Guatemala and journalists from Ecuador and Bolivia, with the coordination of Consejo de Redacción from Colombia and Deutsche Welle Akademie from Germany.

In “Niñas Madres,” I was in charge of the edition of the reportages from Peru and Colombia and participated in the debate with the editors and data analysts about the criteria we should take into account at the moment of interpreting the public databases and crossing the information.

One of the difficulties of the work with data was that in the majority of countries where we proposed ourselves to investigate the issue, the information was incomplete (the cases of Bolivia and Ecuador were the most alarming) or the public data was based on statistical projections.

Facing this challenge, we reviewed in detail the methodology of the databases and interviewed experts who could orientate us to make decisions regarding what information could be reliable to portray reality. Other decision we took was to evince in the reportages the inconsistencies and weaknesses of the public data and how this problem affected the design of a state policy to prevent teenage pregnancy.

For example, between 2012 and September 2016, there were registered in Peru 10 cases of suicide of pregnant teenagers between 12 and 17 years old, and 18 in minors of 20, according to the General Epidemiology Direction from the Health Ministry. But the official data didn’t present the dimension of the issue because there was a high underreporting of information in indicators associated to teenage pregnancy.

Also, there wasn’t an official record of neonatal mortality cases in pregnant teenagers organized by departments. The template employed to gather and analyze these data by the General Epidemiology Direction of the Health Ministry in Peru didn’t include information about the age of the mother, only the place of residence. One of the fears of the authorities was to reveal the possible practices of abortion.

The work with databases demands us journalists to be transparent with our methods and decisions, as well as to show the inconsistencies in the public data. Therefore, it’s very important to explain in a clear and didactic way the process of the work with databases so the readers can draw their own conclusions.

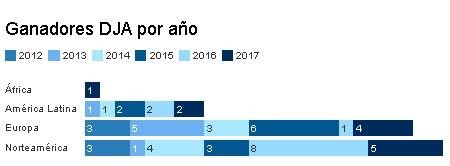

Every investigative project with databases must explain step-by-step the process of work. This is one of the major lessons the reporters of this continent have learned, as we see in the investigation ‘Decida por su cantón’, presented by the newspaper La Nación from Costa Rica regarding the municipal elections from February 2016 in that country.

The Costa Rican newspaper investigated the 605 candidates that were running to occupy 81 mayors. It built a database with their judicial records, administrative sanctions, social security debts and information about their resume.

This was the process:

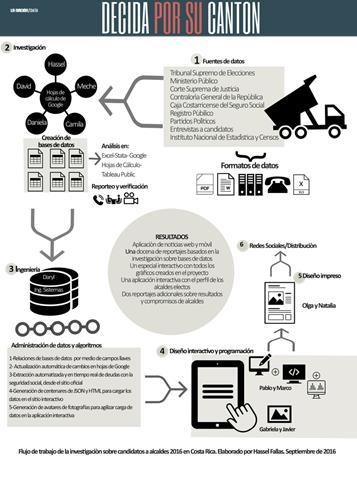

For the investigation ‘Excesses unpunished’ from Convoca, about the environmental behavior of extractive industries in Peru that we described in the first pages of this academic paper, there was also an infographic made to explain how were processed the thousands of documents obtained through more than 100 requests for information. To account this process was fundamental to belie the former Environment Minister, Manuel Pulgar Vidal, who tried to discredit the investigation because it questioned the approval of the article 19 of the law 30230 that forgave millionaire fines in despite of the serious environmental infractions committed.

Transparency tears down the lie of the powerful ones. But also, as ensures the Costa Rican journalist Giannina Segnini, journalists also must be transparent with our methods in the same degree we demand the same from the authorities.

- Explore various formats to publish findings and involve the audience

Usually when we think of publishing journalistic findings based on databases, we think of maps, searchers, rankings, cakes, among other graphics. In data-driven journalism lingo we call that “data visualization.”

However, today it’s possible to publish these findings in various formats. In Convoca, we have experimented not only with the News App (or news applications), but also with podcasts to make a balance of the promises of the president Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (http://promesasppk.convoca.pe/), comics to portrait the years of violence lived in Peru in the 80s and 90s (http://convoca.pe/agenda-propia/episodios-de-la-historia-del-terror-senderista-en-comic) and even a videogame to portray the social and economical impact of tax evasion and avoidance (See: http://ilusionfiscal.convoca.pe/eljuego/).

“The format is one: to creatively account a good story. A story is a life or many of them. When a number has a face, it tells a life and engages the audiences. In the end, is journalism, this means telling stories,” says the Colombian journalist Ginna Morelo.

Ginna Morelo and the Mexican journalist, Lilia Saul, won the Ortega and Gasset Journalism Award with a multimedia special about people disappeared in Colombia and Mexico. The journalists appealed to the interactive graphics, illustrations, videos and chronicles to portray the pain of the relatives of the victims and get in an effective way to the audiences (See: http://www.eltiempo.com/multimedia/especiales/desaparecidos-duelo-eterno/16382245/1/)

Other important aspect is to involve the community of readers in the process of the projects as the team of La Nación Data from Argentina did with the project “Two years of analysis of the listenings of Nisman.”(http://blogs.lanacion.com.ar/data/argentina/el-detras-de-escena-de-la-investigacion-y-clasificacion-de-las-40-000-escuchas-de-nisman/).

After the suspicious death of the Argentinian prosecutor Alberto Nisman, the team of La Nación Data, along with volunteers and university students, initiated a long process of investigation that comprehended the classification of 40,000 recordings, as described the New Ibero-American Journalism Foundation (FNPI). This project was finalist in the Innovation category of the Ibero-American Award Gabriel García Márquez.

The analysis of the recordings implied to upload audios in VozData, a collaborative platform developed by La Nación with the support of Knight Mozilla Open News and Civicus Alliance, for the citizens to help classify the information based on established categories that were then verified by the team of journalists so the citizens could finally download the available data.

For the Argentinian journalist Gaston Roitberg, from the newspaper La Nación from Argentina, journalism with databases opens a great possibility for innovation. And in that path of creativity and journalistic rigor there are many media and journalists in Latin America.

References

Convoca. ABCDatos. 2016: http://abcdatos.convoca.pe/

Convoca. ABCDatos. 2016.‘Lecciones de Panama Papers en Latinoamérica’.http://abcdatos.convoca.pe/edicion/5/lecciones-de-panama-papers-en-latinoamerica

Convoca. Excesos sin Castigo. 2016 http://excesosincastigo.convoca.pe/

Convoca. Patrimonio SA. 2016.http://www.convoca.pe/especiales/patrimonio-sa/

Crucianelli, Sandra. Interview for this report, 2017.

Fallas, Hassel. Interview for this report, 2017.

Fallas, Hassel. La Data Cuenta. http://hasselfallas.com/

Knigt Center for Journalism in the Americas.2017. https://knightcenter.utexas.edu/es/blog/00-18479-periodistas-de-11-paises-unen-esfuerzos-en-sitio-web-sobre-el-caso-lava-jato

Segnini, Giannina. Verification Handbook for investigative reporting, 2015. http://verificationhandbook.com/book2/chapter5.php

Investiga Lava Jato. 2017: http://investigalavajato.convoca.pe/

Morelo, Ginna. Interview for this report, 2017.

Poderomedia. Manual de Periodismo de Datos Iberoamericano. 2014. http://manual.periodismodedatos.org/milagros-salazar.php

Radu, Paul. Interview for this report, 2017

Roitberg, Gastón. Interview for this report, 2017.