Flickr user kymberlyanne

Grafitti on a wall in Gary, Ind. https://flic.kr/p/cCB26J Flickr user kymberlyanne

With a new case in the headlines seemingly every few days, there’s no doubt Indiana is in the grips of a heroin problem. But depending where you live, the severity of the issue can be dramatically different.

In Johnson County, for instance, the skyrocketing case load is obvious and alarming. Prosecutor Bradley Cooper said heroin cases have been doubling each year since 2010. “I see at least one or two a week,” he said. “I had one just this morning. She was whacked out, found in her car giving herself a shot of heroin.”

But Cooper’s counterpart across the state in Daviess County, Daniel Murrie, hasn’t seen anything like that. “I don’t think I’ve filed a case in my four years as prosecutor,” Murrie said.

Still, Murrie’s relief that he hasn’t had to deal with heroin yet is tinged with apprehension. “I just know it’s here,” he said. “I just haven’t caught anybody yet.”

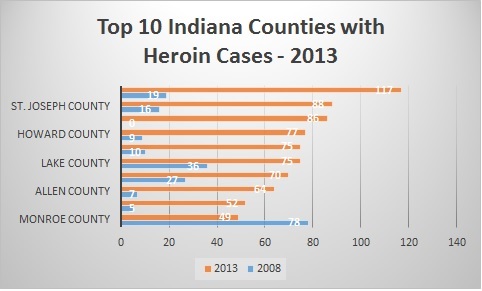

Such county-by-county variations in the statewide spike in heroin cases are clear from an analysis of Indiana State Police data by an Indiana University student reporting project. The data represent all heroin cases sent to State Police labs for analysis from across the state over the past six years.

Overall, the cases increased by 294 percent between 2008 and 2013, from 354 cases to 1,396 last year.

A county by county breakdown reveals which counties are taking the brunt of the impact. In terms of the total number of cases originating within a county last year, Wayne, St. Joseph, and Delaware have the highest totals, with 117, 88, and 86 cases, respectively.

When adjusted for population size, Wayne, Ripley, and Jay have the highest proportion of cases, with 1.64, 1.05, and 1.01 cases per thousand inhabitants. The statewide average is .21 cases per thousand.

Of the 10 counties with the highest proportional number of heroin cases, six are in the eastern part of the state, on or near the Ohio border. Of the remaining four, two – La Porte and Starke counties – are in the northwest corner, near Chicago, while the other – Montgomery and Howard – are in the western and central parts of the state.

On the other hand, many areas in the state have not experienced, or are just beginning to experience, the heroin problem. Of Indiana’s 92 counties, 27 did not send any heroin cases to the State Police labs in 2013.

In 2008, there were 50 such counties. Although 58 counties saw an increase in the number of heroin cases they sent for analysis between 2008 and 2013, 12 counties actually saw a decline over the same period.

The three counties that experienced the most significant decline proportional to their population size were Wabash, Lake, and Monroe Counties.

Searching for an explanation

It is difficult to explain why some counties have been hit harder than others, or to predict where the problem might emerge next. In some cases, the presence of an interstate can be decisive.

“I think we’ve seen heroin in almost every county, but it’s primarily in those counties where the interstate runs through that we’re finding it more and more,” said Noel Houze, an Indiana State Police sergeant based in the southeastern part of the state.

For the spread of a drug like heroin, interstates play a key role as major supply lines. Unlike some other drugs that have afflicted Indiana communities, heroin traffickers rely far more heavily on major thoroughfares for distribution.

“Meth is something that anybody can go on the internet and find the recipe and go to the local Walmart and buy everything they need,” Houze said. “Heroin comes primarily from foreign countries, so it’s going to be trafficked more on the interstate.”

The presence of an interstate in a county does not, of course, inevitably mean there will be a heroin problem in the area. The exact location of the interstate’s route, as well as the position of the county’s population centers, may also be factors.

Source: Indiana State Police data

In the western part of the state, I-74 passes through both Fountain and Vermillion Counties. Yet while Fountain County sent five heroin cases to the State Police labs last year, with a rate of .28 cases per thousand residents, Vermillion County sent none. Fountain County Prosecutor Teryl Martin believes the population distribution within the two counties explains the difference.

“Interstate 74 bisects Fountain County… And then we have U.S. Highway 136 coming right through the heart of Covington,” Martin said. “If you look at the demographics of Vermillion County, the southern third probably contains 75 percent of the population.”

I-74 only passes through the northern section of Vermillion County.

In the southeast, Houze’s experience suggests a similar relationship between interstates and population centers.

“The Batesville police department are a very proactive agency, and I know they’ve made several heroin cases, and I-74 has an exit right there in Batesville. I know they’ve found heroin in Decatur County, up around Greensburg. There again, I-74 runs through Greensburg,” Houze said. “We only have about five miles of I-74 that goes through Franklin County, just that southern tip.”

In 2013, Ripley County, where Batesville is located, reported a total of 28 heroin cases to the State Police labs, with a rate of 1.05 cases per thousand inhabitants. Decatur County reported 10 cases, with a rate of .41 cases per thousand residents. Franklin County reported four cases, for a proportion of .18 cases per thousand.

In terms of total number of cases, it is to be expected that the larger, urban counties would have more incidents simply because they have more inhabitants. Proximity to major urban areas, however, can also affect smaller counties.

“The reason we see so much in southeastern Indiana is because a lot of it is coming out of Cincinnati, Ohio,” Houze said. “Where we’re situated, we’re kind of in that triangle between Indianapolis, Louisville, and Cincinnati.”

Fighting the Problem

Since interstates and the population-dense regions they run through seem to play such a big role in the spread of heroin, they’ve become the focus points for enforcement for agencies at all levels, including the federal Drug Enforcement Agency, which has a state office in Indianapolis.

“I refer to highway 74 from Indy down to Cincinnati as the Heroin Highway,” said DEA Assistant Special Agent in Charge Dennis Wichern. “There’s a couple of real good troopers that work that area that have really interdicted some significant amounts of heroin in the past couple of years.”

The troopers in Houze’s district are doing the interdicting. “We’ve got guys in our interdiction units that patrol the interstates and they’re trained to look for certain signs, certain indicators, through a traffic stop, such as whether a person is acting a little more nervous than usual or if something just doesn’t look right that makes them think that something is going on here.”

If troopers suspect any drug activity, the procedure that follows is simple: They state their suspicion and ask to search the car.

“You’d be surprised at the number of times that people say, ‘Sure, go ahead’ and we find something,” Houze said.

While troopers are equipped to take care of heroin users, effectively putting a cap on the problem would involve stopping traffickers and dealers. Some cases are managed by undercover State Police operations, but Houze said that is generally in the hands of the DEA.

In the past three years, the DEA has opened 4,500 investigations across the U.S. aimed at convicting heroin traffickers.

“The DEA at our level, we don’t go after heroin users,” Wichern said. “Heroin users need help, they need addiction treatment.”

He said effective drug policy is founded on three pillars: enforcement, treatment, and prevention. The first, enforcement, is the DEA’s specialty. Wichern puts it simply: “They need guys like me and my boys. We’re gonna chase around those big dealers and the Mexican traffickers who bring it in, and we’re gonna try to get the evidence and get’em locked up.”

Wichern’s view on treatment is similarly straightforward: “People need help if they get addicted.”

The final pillar, prevention, is a more complicated issue. On one hand, simply informing people of the dangers of heroin is an important step. “We’re trying to get these kids to understand that it’s a very dangerous drug and it’s very hard to get off of, so any way not to take that first hit or that first dose is a very good move,” Wichern said.

Fostering an understanding of heroin requires putting the problem in context, and Wichern and others note the importance of prescription painkiller addiction as a cause of the increase in heroin use.

According to a recent government study, 81 percent of new heroin users started on prescription painkillers such as hydrocodone or oxycodone, and people who use those drugs are 19 times more likely to use heroin.

This trend has been visible across the state.

Johnson County has had a huge rise in both heroin- and pill-related cases over the past few years. In Carroll County – a rural county of “mostly hogs and cornfields,” in Prosecutor Robert Ives’ words – there has been a substantial rise in heroin use, which Ives attributes to powerful painkillers.

Wichern said prescription pills are an especially big problem in larger cities such as Indianapolis.

They are “the most sought-after drugs on the street,” he said. “Those usually cost a buck or two a milligram, roughly, give or take. And then the addiction gets stronger, and [addicts] don’t have the money for that. They shift to heroin, because the euphoric effect is similar and it’s a lesser cost.”

Policy prescriptions

Preventing heroin use, then, also requires preventing abuse of the drugs that often lead to heroin use.

State Rep. Steve Davisson, R-Salem, sees a role for public policymakers in that regard. A Washington County pharmacist, Davisson is a member of Indiana’s Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention Task Force. He has worked on multiple bills related to drug abuse, including one just passed aimed at more effective treatment programs throughout the state. This includes prescribing medications, such as methadone and suboxone, based on an individual’s needs rather than a facility’s restrictions.

“The bottom line is that we want these things to be safe and effective,” Davisson said.

Davisson’s efforts have dealt not only with treatment, but prevention as well. Last year, a bill passed that added regulations to prescription rules. After health facilities began being graded for their patients’ levels of pain, they subsequently prescribed more pain medications. Inevitably, people began manipulating the system to obtain more of these opiates from their doctors, Davisson said.

“They have been feeding the frenzy in a way,” he said. “What we’re trying to do is reel it back a little bit.”

One frustration Davisson has noted, however, is that an effort to take care of one drug problem often means another problem fills the void. That’s the story of the drug cycle: as certain drugs are more effectively dealt with, others rise to take their place.

“We tried to curb the prescription drug abuse and now they’ve shifted to heroin because it’s really cheap,” Davisson said.

Which is worse – heroin or meth?

While the rise in heroin and synthetic opiates in Indiana poses distinct dangers, the increase is not isolated, acting instead as an added burden on a state already struggling with other drug problems.

In comparison to heroin, known for being one of the most deadly and dangerous drugs on the streets, methamphetamine is more commonly known for its enormous collateral damage to communities. And with the ebb and flow of different drug fads, methamphetamine appears to be the most longstanding and persistently problematic.

“Of course heroin has come and gone. I remember when I started 35 years ago, and I had heard about Mexican black tar and there were some people around here using it, and then it died out,” said Fountain County Prosecutor Teryl Martin. “And then we had powdered cocaine come in, and it died out. Then we had crack cocaine come in; died out. And then meth hit, and my lord, it hasn’t died out.”

The same goes for Jackson County, according to Prosecutor Amy Marie Travis, who has been battling the growing heroin trend in her southeastern Indiana county for the past few years.

“My biggest problem with heroin and synthetic opiate addiction is there are people dying fairly commonly. That’s my scariest thing with that drug,” she said. “(But) if you ask me if it’s the worst, probably no. That’s methamphetamine.”

Prosecutors across the state say both heroin and methamphetamine are the most troubling drugs for their counties, but for different reasons.

“Meth is the drug with the most collateral damage,” Travis said. “When people are addicted to meth, it decreases their sense of right and wrong and their judgment, and increases sex drive. At meth houses, all the kids have been molested. Manufacturing meth damages the environment.”

“But with that being said,” she added, “synthetic opiate and heroin addiction cause the most deaths.”

And Travis said heroin can cause a great deal of collateral damage as well.

“The people addicted are dying. There’s damage to family members, and they become unemployable. They’re just high all the time. And eventually with any drug addiction, they’re stealing and burglarizing to sustain it,” she said.

State Police Sgt. Houze said it may be easier to combat methamphetamine because there is more experience dealing with it, and a number of laws have already been enacted to help fight it. Among other things, the state has set up databases to track purchases of products used to manufacture methamphetamine.

La Grange County Prosecutor Jeff Wilde said the methamphetamine problem has even decreased in the past 12 years because police are more experienced with dealing with the problem. But he said heroin is different because until the dealers are found, law enforcement doesn’t know where to begin.

Resource Strain

In any case, prosecutors and others say the rise of heroin has placed a new strain on the resources of Indiana’s law enforcement agencies.

“We’re always understaffed. We always don’t have enough money. I’m on call 24 hours a day. I don’t know what it would be like not to be strained,” said St. Joseph County Prosecutor Amy Cressy. “It’s a different animal on a different day. Not only are we crumbling under the weight of new heroin cases, we’re crumbling under the weight of all the cases all the time.”

It’s a common sentiment among prosecutors.

“Our office’s resources have absolutely been under strain due to the increase,” Jackson County’s Travis said.

She emphasized partnership across law enforcement agencies as a key strategy in trying to reign in heroin use.

According to Fountain County Prosecutor Martin, prosecutors have to adapt to keep up, especially on complicated drug felonies that take more time than other types of cases.

“You’ve got to be learning all the time because the tricks they’re using to get the drugs are changing all of the time,” Martin said. “But that just means you take work home on Saturdays and you work Sunday night to get ready for Monday.”

Looking Forward

In the first quarter of 2014, State Police labs received 174 heroin cases compared to 304 cases in the first three months of 2013. The numbers are promising, but officials say it is far too soon to tell whether the trend in heroin use is leveling off.

“It is spot on to say it is unpredictable,” said State Police Sgt. Curt Durnil. “There are a plethora of different reasons for the fluctuating numbers. I think we would need more data over the course of more years to say either way.”

The unpredictably of the problem is illustrated by the fluctuating numbers within individual counties. Delaware County, which sent 15 cases to the State Police labs in the first quarter of 2013, sent 18 over the same period in 2014. Wayne County, which sent 20 cases in the first quarter of 2013, has sent only six cases so far this year.

Yet, Despite the seemingly inexplicable fluctuations and dramatic increases in the number of cases from year to year, there may still be reason for cautious optimism.

“I don’t know if the heroin problem is going to expand much more simply because you’re only going to have a certain percentage of your population that’s going to get involved,” Martin said, “And once you get up to that percentage, it will stabilize at that point.”

Even if the problem eventually stabilizes, it is by no means certain that it can be quickly reversed. Given the complexity of the causes and the significant variations in the outbreak from county to county, the way toward rolling back the heroin epidemic in Indiana is unclear.

“It seems like you’re chasing your tail sometimes on this legislation because every time you do it a new problem comes up,” Rep. Davisson said. “Honestly I don’t know what the answer is on the heroin. It’s a street drug, it’s cheap, and the best we can do is to prevent people from getting involved with it, but how do you do that? That’s the question.”

These stories were reported and written by students in Prof. Gerry Lanosga’s investigative reporting class at Indiana University in Spring 2014.

My daughter died January 25th this year she had been clean 50 days that I know of before the acquaintances as she called them got a hold of her, we are giving the police some time to find the person and if not we will find him or her and fix it. Drug dealers are running our children and killing them off and there isn’t anything we can do its a very defeating feeling to fight these dealers for this long and still lose our daughter to them she was only 20 years old and wanted to be done with all of it, she wanted to have a life and knew she wasn’t going to have one with the people she was hanging with. Just getting through a day is almost to much to take when you lose your child.

Pingback: US Heroin Epidemic: Growing Rates Of Addiction And Overdose Reported In New Jersey, Kentucky, Indiana | The AmericUSumter Observer

We are trying to get some answers for a mother who’s son overdosed and frankly are appalled at a mother being told it was her fault, and some Ripley county deputies telling her to her face that she’s a bad mother, they are not at all interested in getting answers they want to believe the friend of our loved one who was never able to tell us again, so many questions and we believe that our vigilance is what’s gonna make them get answers, WE ARE NOT GONNA REST TIL SHE GETS ANSWERS

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Your graph “Top 10 Indiana Counties With Heroin Cases” only names 5 counties on the left (vertical) axis; what are the names of the other five counties? I am doing a master’s degree thesis on heroin in Indiana, so I would like to know.

Sincerely yours,

John Freeland

johnfreeland@bluemarble.net

I am looking for some place to get help for my son and his girl friend. They want to get clean but they have been turned away at many places, because they did not have the money or the place just wasn’t taking on any more patients . Can some one give me a place to send them so they can get clean or get on a maintenance drug without paying a fortune to do it. Indiana has this problem but there is really has no where to get help unless you have a lot of money or great insurance, there needs to be affordable help and enough certified doctors to deal with this so we don’t have more people dying from this terrible disease. Looking for out patient program but will also consider in patient if they take insurance.

I believe I can assist you. I’m going to do some double checking and I’m quite busy bit please email if you still need suggestions.

What about shellbyville I see tweakers all the time