This is a research paper that was accepted for but not presented at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference 2017 Academic Track, which IJEC organized and covered. For more research and coverage of GIJC17, see here.

Challenges in doing investigative reporting: A Zambian case study

Running Head: Investigative reporting: Zambia

By Twange Kasoma, Ph.D Radford University and Greg Pitts, Ph.D. Middle Tennessee State University

Abstract

First, the newly installed Patriotic Front government of Zambian President Edgar Lungu launched indiscriminate shutdowns and license revocations against private media (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2016) deemed to oppose the PF government. More recently (April 2017) was the arrest of Hakainde Hichilema — the president of the United Party for National Development, Zambia’s biggest political opposition — on treason charges (Wall Street Journal, April 19, 2017). The treason charges, punishable by death, stemmed from allegations that Hichilema’s motorcade failed to yield to Lungu’s presidential convoy. Although Hichilema was eventually released after four months in prison following a deal proctored by the Commonwealth Secretary General Patricia Scotland, local, full-fledged investigative journalistic coverage of his court proceedings was at best spotty.

Ironically, these actions come when a survey of members of parliament finds overwhelming support for press freedom among the country’s legislators (Kasoma & Pitts, 2017). Yet there appears to be a reluctance to implement changes that would provide for a freer press system. Using the results of this survey as a backdrop, in-depth interviews were conducted with a select number of journalists and editors on the challenges posed in conducting investigative journalism and day-to-day enterprise reporting in Zambia under the current political environment with a deteriorating press freedom index (Freedom House, 2017). The results elaborate on the professional orientations of the journalists and editors interviewed to understand their motivations for continuing in a career with ever-difficult challenges to professional success.

Key Words: Zambia, press freedom, media use, investigative reporting

Introduction

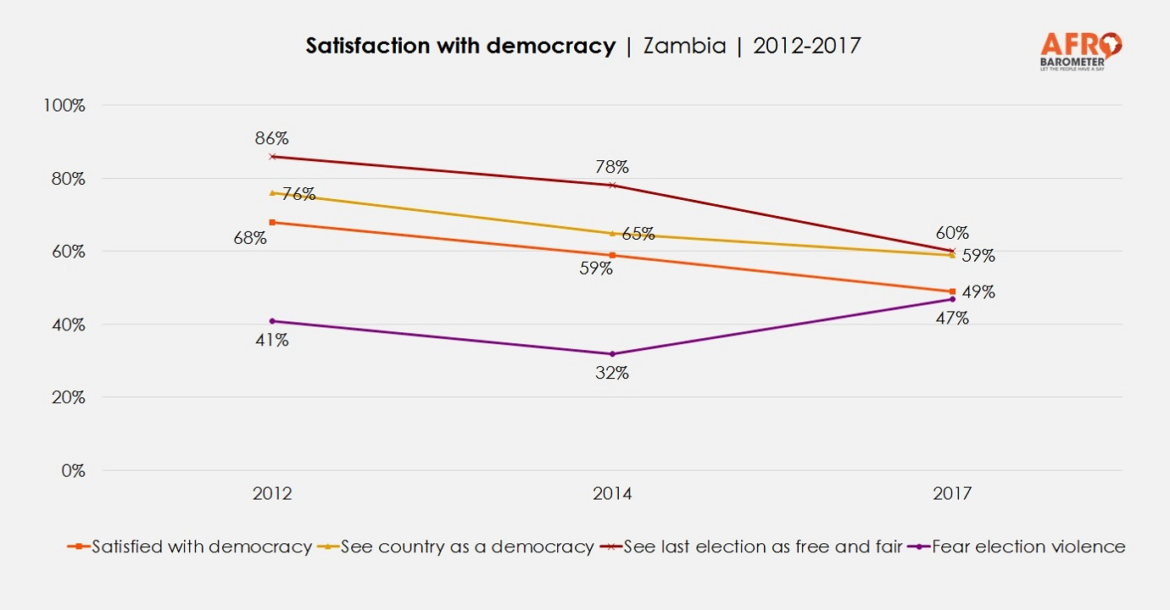

Starkman (2014) equates investigative journalism with accountability journalism and posits that it serves as “the mother’s milk of the journalism industry”. Investigative journalism lays the very foundation upon which the media’s watchdog role gains its impetus. According to Kovach and Rosenstiel (2014), the creation of the Pulitzer Prize in 1964 as an award for journalists who demonstrated good investigative reporting provided a division between journalism and other forms of communication. Noteworthy is that through investigative journalism “the earliest journalists firmly established as a core principle their responsibility to examine the unseen corners of society” (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2014, p.143). Without a free press, however, the ability to investigate issues of importance to the public is maligned, and with it the very essence of a democracy. According to Afrobarometer (2017), although Zambians have long been committed to the ideals of democracy, the last five years have seen a significant drop in satisfaction with the way democracy is working (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: Afrobarometer (2017)

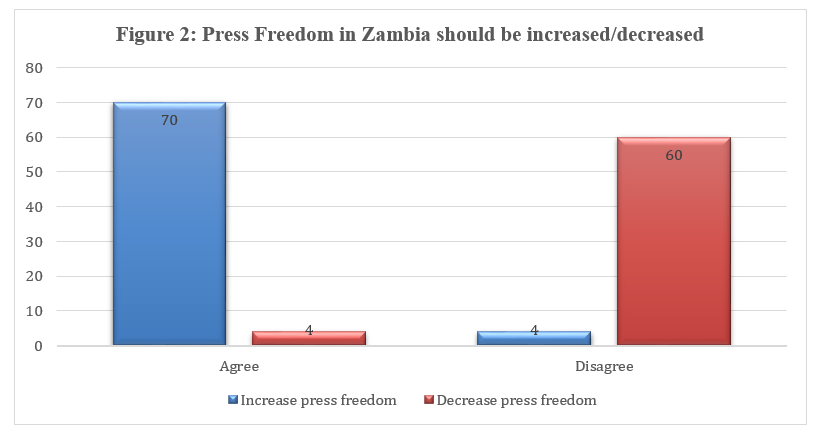

When we rewind to 1991 when the wave of democratic change (Ake, 1996) swept across the continent, Zambia was hailed as exemplary. Pye (2004) noted with optimism that as multiparty democracy took deeper roots in Africa, “we (could) expect greater appreciation for the values of press freedom and the protection of the rights of professional communications” (p. 50). The aforementioned make the current dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working in Zambia — which should be viewed concurrently with the deteriorating press freedom index (Freedom House, 2017) — concerning. Interestingly though, a series of investigations into perceptions of members of parliament about press freedom suggest strong support (Pitts, 2000; Kasoma & Pitts, 2017). As noted in Figure 2, about 95 percent (n=70) of Parliamentarians surveyed agreed or strongly agreed that press freedom in Zambia should be increased. In the same survey, about 94 percent (n=60) disagreed with the counterpart statement that press freedom in Zambia should be decreased.

Source: Kasoma & Pitts, 2017.

Note: Although N=74, for the ‘Decrease in press freedom’ variable, eight Parliamentarians neither agreed nor disagreed with decreasing press freedom while two did not respond.

What pertains on the ground however is a reluctance to implement changes that would provide for a freer press system. This was particularly evident following the August 2016 elections when the newly installed Patriotic Front government of President Edgar Lungu launched indiscriminate shutdowns and license revocations against private media (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2016) deemed to oppose the PF government. In order for democracy including the essential elements of press freedom, individual rights, and competitive elections to develop successfully, there is a leadership mind-set that must be overcome (Blake, 1997).

Press freedom requires two things: parallel development of an independent and responsible press, and an elected government willing to allow the press to function without interference. Speaking to both conditions and specific to Zambia’s case, Kasoma (2000) asserts that, “My view is that the press for as long as it is relatively free and independent can, in some measure, help to democratize society” (p. 40). Historically, African governments have been unwilling to cede their control over media and to establish independent, transparent, and credible regulation of the media (Callamard, 2010). Although theoretically, an unfettered press should go hand in hand with development, African development, politically and economically since British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s “winds of change” 1960 pronouncement, has been a contentious issue for more than a half-century. Lahav (1985) identifies the obvious conundrum this creates. It is difficult for mass media to promote civil society development when the media system reflects the society in which it operates and that society is unable or unwilling to sustain a press vibrant in news gathering and in support of a local economy.

The seemingly bleak outlook has not necessarily deterred investigative journalism in Africa. Saleh (2015) demonstrates via a series of snapshots African journalists operating in conditions of risk and amidst coercive societies as they strive to attain the truth. In Zambia, Kasoma (1997) wrote about hard hitting exposés by the now defunct church-owned National Mirror. It is hard to separate the fact that the National Mirror is no more from the harsh reality of practicing investigative journalism in Zambia. Clearly, investigative journalism is by no means an easy undertaking anywhere in the world (Svensson, 2017; Starkman, 2014), but especially so on the African continent. Among the impediments that Yusha’u (2009) identifies that hinder the practice of investigative journalism in Africa include poor remuneration, bad working conditions, corruption within the media, and the clientelism-laced relationship between publishers and politicians. Aiyetan (2015) cites cash-strapped newsrooms across Africa as phasing-out time-consuming investigative reporting.

In Zambia, the current political and legislative arena also poses its own challenges. MISA Zambia (2017) reports that Zambian President Edgar Lungu has given police the power to ban material deemed threatening to public safety. President Lungu granted the threatened state of emergency to deal with a string of arson attacks but the authority gives police the ability to ban public meetings, impose curfews and restrict movements, and prohibit the publication and dissemination of matters regarded as prejudicial to public safety. The actions effectively nullify citizen protections provided by Article 20(1) of the Zambian Constitution. A further consequence of this legislation, according to Bariyo (2017), is that it allows President Lungu to impose broad restrictions on the media. Invocation of laws restrictive of press freedom is not new (MISA Zambia, 2013), as the press tends to be perceived as an enemy of government (Kasoma, 1995). What is new is the heightened nature of such invocations under the current government (Kasoma & Pitts, 2017), all while stagnating the passage of progressive legislation such as the Freedom of Information Bill (MISA Zambia, 2016).

The dominant journalism paradigm in most of Africa has been development communication for conveyance of useful information through media outlets to improve the quality of life of listeners and readers, and unite nations to support the state (Rogers, 1990). But the false idea that development news is an effective replacement for robust, independent and investigative journalism clashes with the role of journalism outside much of Africa. The need for insightful news contributions about Africa from a healthy (investigative) journalism environment across the continent is even more important when viewed from the changed global reporting landscape. International news coverage once consisted of stories from Western reporters, sometimes characterized as promoting stereotypes or a colonial history (Bunce, 2015; Savelsberg, 2015). The mix of stories written by outsiders create a manufactured view of a continent as country, with famine and civil unrest from border to border. But changing news budgets have changed coverage patterns. Wu and Hamilton (2004) found a dramatic reduction in the number of American nationals posted abroad. Dwindling news budgets have resulted in more international news coverage dependent, to a large extent, on journalists in the region (Bunce, 2015).

When local reporters are depended on to report to a national audience, the first challenge they face is the ability to practice their craft within a country with a chilled press environment and few, if any protections for journalists. Bunce (2015) noted the results of his 2011 research where he concluded “that local journalists may be more vulnerable to persecution of repressive governments” (p. 45). Thus, a healthy, supportive and sustaining relationship between press systems/ journalists and government is needed to ensure at least reasonable, if not robust reporting as the responsibility for international reporting of news from across Africa shifts to local journalists. Thus a slippery-slope exists for Zambia and other countries seeking democracy: without a free press and individual liberties there can be no democracy yet without democracy there cannot be a free press and individual liberties.

Confounding the problems of a free press in many African countries is the absence of democratic governance to promote investigative reporting. Raphael (2005) identifies the importance of officials and jurists as reporters’ best sources, collaborators and defenders of investigative reporting. Without the parallel tracks of good governance, civil society and a press system with independence from political and economic power, there can be little hope of relationships between reporters and government officials to support investigative journalism. Raphael (2005) is blunt when noting that, “Investigative journalism will not survive without sustaining the web of relationships with government that ensures that this more important kind of news for democracy is funded, distributed, and protected from extinction…” (2015, p. 245). This paper examines the state of investigative reporting in Zambia through a series of in-depth interviews with working journalists and editors.

Method and brief profile of interviewees

A case study, utilizing in-depth interviews, was the preferred methodology. Wimmer and Dominick (2014) note that case studies are advantageous when it comes to gathering descriptive and explanatory data. This is because the researcher is afforded “the ability to deal with a wide spectrum of evidence” (Wimmer & Dominick, 2014, p. 144). A total of twelve journalists and editors representing both privately-owned and state-owned, government-controlled media outlets, which included newspapers, radio, and TV, were interviewed over a two-week period. Seven were women and five men. Their professional experience ranged from two years to nearly twenty years. The interviewees’ educational credentials were also varied. They included journalists and editors who had diplomas (the equivalent of an associate degree in the U.S.) in journalism from Evelyn Hone College as their highest educational attainment. Others had a degree (a resultant of four years of study) in mass communication from the University of Zambia (UNZA). There was also a unique case of an editor at a privately-owned radio station who held a law degree. A few interviewees reported returning to school, as part-time students, to pursue studies in fields such as development studies.

All twelve interviewees fervently discussed how, despite the many challenges faced, passion for serving the public is what led them to pursuing a career path in journalism and what makes them continue to persevere. One interviewee posited that as they work for student media to gain professional experience, they already get a dose of the challenges they will face upon graduation, especially where intimidation of journalists is concerned. “UNZA Radio is a classic example of how the police walk in and intimidate student journalists for criticizing the state on The Lusaka Star, a current affairs magazine show,” the interviewee states.

Challenges journalists/editors face in doing investigative reporting

A question posed to all twelve respondents was: “In cases where you have had to engage in investigative reporting, what challenges have you faced in covering those stories? Cite some specific instances/examples.” The main challenges the interviewees highlight are: (1) Lack of legal provisions/instruments that grant journalists access to information and running parallel to that the maintenance of archaic laws on statute books that limit access; (2) Government red tape; (3) Inadequate funding and institutional bureaucracy; (4) Political violence; and (5) Inadequate training.

Lack of Access to Information

A number of the interviewees pointed to access to information as a crucial challenge. Since the democratization process that took place in the early 1990s that saw Zambia transition from a one-party to a multi-party state, subsequent governments have flirted with the idea of passing a Freedom of Information Bill (FOIB), yet none has. A male journalist at a privately-owned newspaper vividly describes the dilemma journalists face:

Access to information is the greatest challenge. Zambian sources, especially government sources, are hard to find (i.e. for hard copy documents) and hard to speak to (i.e. human sources). For example, recently I wanted to unearth corruption in the Zambia-Malawi maize deal saga, but I couldn’t due to lack of access to information.

For this journalist, the speedy enactment of FOIB would be a step in the right direction, but he is also quick to note what else needs to be fixed legislative-wise:

Lately, harsh laws hinder investigative journalism in Zambia. Draconian laws in the Penal Code, such as publication of false news, scare most of us from becoming too investigative. Moreover, for fear of arrest and jail, most of us just decide to write stories from press events and statements.

The interviewees further noted that the recent invocation of Article 31, which gives the President powers to declare a threatened state of emergency, has further compounded the access to information problem. As reported by the Wall Street Journal: “State-of-emergency legislation would let President Edgar Lungu impose broad restrictions on the media and freedom of assembly and movement.” A female journalist at a privately-owned radio station provided the following insight about the impact currently being felt as a result of the invocation of Article 31:

Currently, there is an element of fear as journalists are not entirely free to report on pertinent issues. This is because of the state of Threatened Public Emergency Status which was declared by the President in accordance with Article 31 of the republican constitution. According to this Article, the President has power to make such a proclamation when he sees a situation, which if left unchecked, has the potential to result into a declaration of a State of Emergency. Even though the enactment of Statutory Instrument Number 55 of 2017 [Article 31] does not make any reference to media, the declaration has created a lot of caution and self-regulation in the media circles as people are scared of being detained for extended periods of time as the law permits.

The fear of detention became one editor’s reality at a privately-owned radio station as she pursued an investigative story highlighting the discrepancy in the administration of the BCG vaccination in newborns and what impact this had. Babies born at Zambia’s biggest referral hospital — the University Teaching Hospital — received the vaccination upon birth while in other health centers and clinics around the country there was a one-week time lapse. Here’s how the editor narrated her ordeal in pursuing this story:

I was covering a story that required me to package my news item as a report on Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine that is administered in Zambia to newborn babies as a prevention of tuberculosis. Babies born at the University Teaching Hospital (UTH) are vaccinated immediately after birth while babies born in clinics are administered the vaccine after a week. Before embarking on my investigation I got permission from a doctor in high authority from the Ministry of Gender and Child Development and made an appointment to see a doctor at UTH. After a successful interview with the doctor I went ahead to interview breastfeeding mothers who had given birth from clinics [and were at UTH for referrals] when a security guard told me that it was unlawful for me to carry out an interview with the women at the hospital because I was not in the company of a UTH Public Relations Assistant Officer. I was detained and threatened that I was going to be charged with impersonation. They attempted to confiscate my recorder which I resisted. I later asked for permission from the security supervisor to contact my superiors which I was allowed. After conversing with my superiors they released me.

Government Red Tape

Interviewees also bemoaned the government red tape that hinders their investigative endeavors. A male journalist at a state-owned newspaper noted:

In my coverage of investigative stories, government officials, especially junior officers and at times directors take long to respond to queries, especially those perceived to be too investigative in nature. They choose to refer journalists to their seniors who also at many instances advise us to write a press query which they may never respond to.

For journalists who work for state-owned media they face a further hurdle of government censorship as part of the red tape, especially where investigative stories are concerned. As a female journalist at a state-owned newspaper narrated:

I decided during COP21 [Climate Change Conference] in Warsaw to live at the same hotel where the Zambian delegation was living. I also took time to go shopping with them whenever they were going shopping (…) they would skip the meetings and most of the delegation were buying fitting materials [building implements] for the houses they were building back home while others had orders of clothes, shoes and related stuff for people back home. I had gathered quite interesting stories about the delegation and their behavior when they go for such meetings but this story was never supported by the minister and my office thought it was very sensitive so it was never published. It is difficult to have an investigative story published if it is highlighting the ills of government officials.

Inadequate Funding and Institutional Bureaucracy

Delving into institutional bureaucracy, a male journalist at state-owned television station reports that: “It is very difficult to engage in investigative reporting at my place of work due to lack of a recognized support structure to support the beat.” He adds that this is also evident in resource allocation: “A car and camera is shared among no less than four reporters. This makes it difficult and almost impossible to conclusively follow up an investigative lead story. That’s why most stories that are done are scheduled and event based.” Where inadequate funding is concerned, a female journalist at a privately-owned radio station aptly explains its negative impact on doing investigative journalism thus:

Financial constraints remain one of the biggest challenges in my quest to engage in investigative reporting in that it is difficult to travel to far-flung areas to cover a story because you will need transport, accommodation and sometimes people that have the information request that you pay them something for them to help you.

For example, I wanted to do a story about street kids that have been raping women in the night. The street kids requested that I give them some money for them to disclose the name of their friend who raped an identified lady.

Political Violence

The interviewees also pointed out that now more than ever before, political violence targeted at journalists has become commonplace. A female journalist at a privately-owned radio station explains how she and a colleague almost fell prey to political violence:

Political interference is also a challenge especially from party supporters. Sometime last year, my colleague from another radio station and I were almost beaten by party cadres because they felt we had written false stories about their president.

According to a male editor with ten years of experience at a privately-owned radio station, utterances by the police whom journalists should seek solace from have had their own negative impact:

The Inspector General of Police recently warned during a media briefing that media houses that publish or broadcast content that is deemed to alarm the nation risk being closed. That statement has caused a lot of fear amongst the journalism fraternity. There is a lot of self-censorship by journalists for fear of offending the powers that be.

Inadequate Training

Waisbord (1996) in studying Latin American journalists found that lack of training was an impediment to investigative reporting. Similarly, interviewees for this study also report the need to be better educated in not only how to be more strategic and deliberate in their pursuit of investigative journalism, but also how to cope with the challenges. One journalist, a female at a privately-owned radio station, noted that education in entrepreneurship would be helpful in overcoming the funding constraints they face. Another, a male journalist at a state-owned newspaper observed that: “There is need for us journalists to continuously sharpen our skills through training in order to meet the demands that come with the reporter working in the 21st century.” Adding that the investigative journalism landscape “will even be better when all journalists embrace [training in] professionalism and the need to adhere to media ethics.”

Way Forward for Investigative Journalism in Zambia

The term development in the African context has been tossed about with minimal sincerity and little impact on the quality of the lives of the citizens across the continent. Development for some leaders has come to mean establishing a media system that galvanizes support for the political party in power while pretending to unite the citizens. But if development is to enable a country to transition to democracy, development and governance must support not only free and fair elections but also free press and free speech. This includes a system promoting openness for journalists to access information from civil servants, including police and government record keepers.

The job of the press is to report the events taking place in the country. While many stories may be positive, even negative stories—investigative stories—are not meant to embarrass but to focus attention on problems of governance, administration or corruption that should not exist. The press can be a partner but it must be an independent partner, free of intimidation, whether from State House or local police officials. The challenge for any government is to resist being thin-skinned and recognize that journalists report issues of economic, social and civil concern; these are issues of concern to the citizenry and they should concern the officials representing the citizens. This is true for the United States where the current president blusters about fake news to Zambia with concerns of a threatened state of emergency and potential speech and press suppression. Saleh (2015) notes the importance of the free and independent press to promote not only immediate self-improvement but also improvement for future generations. Elected officials who campaign for office on the promise of developing the nation should likewise campaign in support of a free press that will address issues for improvement of future generations. Aiyetan (2015, p. 18) put it best when noting that investigative journalism “holds so much potential to have an impact on good governance and the substance of democracy and development…”

The five challenges we have identified through this series of interviews are within the scope of government to address. The challenge for elected officials is to remember why they campaigned for office in the first place. A transparent and freely operating government will create a climate for daily reporting and investigative work to examine important issues. An important step in that direction echoed by all the interviewees for this study is that the government should prioritize passage of FOIB to enable them access to information.

References

Afrobarometer (2017). Zambians sound alarm for eroding democracy, Afrobarometer survey shows. Retrieved from http://www.afrobarometer.org/press/zambians-sound-alarm-eroding-democracy-afrobarometer-survey-shows

Aiyetan, D. (2015). Constant Change in Investigative Reporting in Africa. In Progress of investigative reporting overseas. Coronel, S, Aiyetan, D., Mulvad, N. and De Toleto, J. IRE Journal. 38: 2. Retrieved from Ebsco Host..

Ake, C. (1996). Democracy and Development in Africa, Washington, D. C.: The Brookings Institution.

Bariyo, N. (2017, July 6). Zambia’s president calls for sweeping emergency powers as opposition crackdown intensifies. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/zambias-president-calls-for-sweeping-emergency-powers-as-opposition-crackdown-intensifies-1499332951

Blake, C. (1997). Democratization: The Dominant Imperative for National Communication Policies in Africa in the 21st Century, Gazette 59, 253-269.

Bunce, M. (2005). International News and the image of Africa: New Storytellers, new narratives? In J. Gallagher (ed.) Images of Africa, Manchester, United Kingdom: University of Manchester Press. From http://www.jstor.org.

Callamard, A. (2010). Accountability, Transparency, and Freedom of Expression in Africa. Social Research, 77:4, 1211-1240.

Committee to Protect Journalists, (2016, November 8). For Zambia’s press, election year bring assaults and shut down orders. Retrieved from https://cpj.org/blog/2016/11/for-zambias-press-election-year-brings-assaults-an.php.

Freedom House (2017). Zambia: Freedom of the Press 2017. Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/2017/zambia.

Kasoma, F.P. (1995). The role of the independent media in Africa’s change to democracy. Media, Culture and Society 17(4), 537-555.

Kasoma, F.P. (2000). The press and multiparty politics in Africa. Tampere, Finland: University of Tampere.

Kasoma, T. & Pitts, G. (2017). The Zambian press freedom conundrum: Reluctance rather than resilience. Journal of African Media Studies, 9(1), 129-144.

Kovach, B. & Rosenstiel, T. (2014). The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect, (3rd ed.). NY: Three Rivers Press.

Lahav, P. (1985). Press Law in Modern Democracies: A Comparative Study, New York: Longman Publishers.

MISA Zambia (2013). State of media freedom in Southern Africa 2013: Zambia National Overview 2013. In So this is democracy? (pp. 138-151). Retrieved from http://www.misa.org/files/STID_2013_Zambia.pdf.

MISA Zambia, (2016). State of the media in Zambia. Retrieved from http://misa.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/State-of-the-media-Zambia-Third-Quarter.pdf

MISA Zambia (2017). Threatened state of emergency cuts freedom of expression. Retrieved from http://zambia.misa.org/2017/08/30/threatened-state-emergency-cuts-freedom-expression/

Pitts, G. (2000). Democracy and Press Freedom in Zambia: Attitudes of members of Parliament toward media and media regulation. Communication Law and Policy (5), 269-294.

Pye, L. (2004). Communication and Political Development. In C. C. Okigbo and F. Eribo (Eds.), Development and Communication in Africa, (pp. 47-54). Oxford, UK: Rowman and Littlefield.

Raphael, C. (2005). Investigated Reporting: Muckrakers, Regulators, and the Struggle over Television Documentary, Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. From http://www.jstor.org.

Rogers, E. (1990). Forward. In F. L. Casmir (Ed.), Communication in Development, (pp. vii-viii). Norwood, N.J.: Ablex.

Saleh, I. (2015). Digging for transparency: How African journalism only scratches the surface of conflict. Global Media Journal: African Edition, 9(1): 1-10.

Savelsberg, J. (2015). Rules of the Journalistic Game, Autonomy, and the Habitus of Africa Correspondents. In Representing Mass Violence: Conflicting Responses to Human Rights Violations in Darfur (pp. 205-221). Oakland, California: University of California Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1ffjn3g.14.

Starkman, D. (2014). The watchdog that didn’t bark: The financial crisis and the disappearance of investigative journalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Svensson, M. (2017). The rise and fall of investigative journalism in China: Digital opportunities and political challenges. Media, Culture & Society. 39(3) 440–445.

Waisbord, S. R. (1996). Investigative journalism and political accountability in South American democracies. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 13, 343-363.

Wimmer, R.D. & Dominick, J.R. (2014). Mass Media Research: An Introduction. 10th edition. Wadsworth. Boston: MA.

Wu, D. & Hamilton, J. (2004). US Foreign Correspondents: Changes and Continuity at the Turn of the Century. Gazette: The International Journal for Communication Studies, 66(6), 517-532.

Yusha’u, M.J. (2009). Investigative journalism and scandal reporting in the Nigerian press. Equid Novi: African Journalism Studies, 30(2): 155-174.